Gamma-ray bursts, or GRBs for short, are flows of high-energy photons that in milliseconds or minutes release as much energy as the Sun ever will. Astronomers can observe these events from billions of light-years away.

GRBs’ colorful history begins in 1967 with the Vela satellites, which the United States deployed to detect nuclear weapons. While analysts did not find anyone breaking treaties, they did find strange flashes of gamma radiation in the observations. They thought it was weird but definitely not bomb-like, so they filed the data away.

These flashes, however, continued to show up in the data. After 16 events, scientists determined the radiation was not from Earth (specifically not the Soviet Union), which meant the findings could be declassified and were published in 1973.

Now that GRBs were out in the open, scientists could study them. They were so bright that many believed they had to be from our own galaxy.

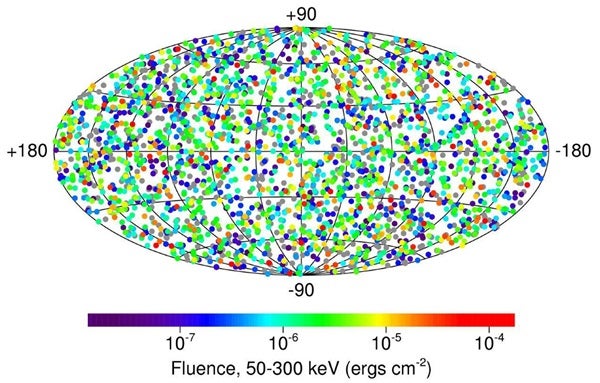

But in the 1990s, NASA’s Compton Gamma Ray Observatory helped disprove that idea. It saw GRBs all over the place, homogenously distributed across the sky. If GRBs were internal to the Milky Way, they would have been more concentrated along its plane.

After BeppoSAX detected a GRB, an optical telescope observed the same spot and saw visible light — an afterglow! This light allowed scientists to determine the distance to the source. At 6 billion light-years from Earth, it was well out of our galaxy. For GRBs to be extragalactic, though, they must be extremely bright.

Forty-six years after their accidental discovery, scientists know a lot more about GRBs.

GRBs come in two flavors: short and long. Short bursts last less than two seconds and account for 30 percent of the population. Scientists believe they happen when a combination of neutron stars, white dwarfs, or black holes coalesce and form a black hole. As they spiral toward each other, a disk of material forms and releases a burst of energy.

If the details sound fuzzy, it’s not because of my narration. Scientists are still working this problem out.

In both cases, the gamma rays come from a very small space and are highly directed — they don’t spread out in a sphere like light normally does. In order for our telescopes to observe them, they have to be pointed directly at us.

Scientists estimate that a GRB happens every 100,000 to 1 million years in a galaxy like the Milky Way. But they only affect what’s directly in their path. A GRB is pointed at the Earth much less often — every 5 million years — which is a totally comforting thought. An unfortunately pointed local GRB could annihilate even the most hardy bacterial species. And those guys are hardy.

But, for now, scientists are happy to study these bursts in other galaxies. Now that they have pinned down GRB origins, they hope to determine exactly what mechanisms could release so much energy into the universe.

Expand your knowledge at Astronomy.com

Check out the complete Astronomy 101 series

Learn about our stellar neighborhood with the Tour the Solar System series

Read about the latest astronomy news