In 2010, I started making YouTube videos to help people glimpse interesting celestial objects, from the planets to galaxies and everything in between. All the while, I also tried to educate them about observing equipment and the issue of light pollution. The series, Eyes on the Sky, celebrated its 12th anniversary this November.

Since the program’s inception, I’ve been fortunate enough to both lead and participate in live outreach events across the greater Chicagoland area, despite its light-polluted skies. My outreach adventures have also taken me to suburban libraries, local forest preserves, community centers, and even to California’s redwood forest and Pennsylvania’s Allegheny National Forest.

Suffice to say, I’ve interacted with many amateur and experienced observers, both virtually and in person, during that time. And one popular question that always seems to crop up, no matter the observer’s experience or desired target: “How do you know where to find that?” Once I noticed, I started making a mental list of commonly requested targets, and eventually I started writing them down. Since 2012, I’ve been tweaking this master list based on in-person feedback.

With so many beginner observers turning to the skies during the pandemic, a related question has been popping up online: “What deep-sky objects should I hunt down after I’ve observed the Moon and bright planets?” The response I’ve often seen from others is to start with the Messier list. But I think that’s misguided advice.

Stay with me; let’s walk through this. A logical beginner might think: “OK, what’s the first object on the Messier list? Oh, Messier 1, the Crab Nebula. I’ve seen photos of that online — it is amazing! I just got a telescope for Christmas and this object is in my sky tonight. So, let’s start at the start.”

Now imagine the disappointment of that beginner after observing the Crab Nebula through a 60mm or 70mm refractor under heavily light-polluted skies — assuming they can even find it. I’ve had trouble viewing M1 with a 76mm reflector using averted vision under decent skies, and I’m a rather experienced observer.

Remember, Charles Messier and his assistant Pierre Méchain did not compile the famed list because they were looking for a bunch of great and bright nebulae for amateurs. Messier was a comet hunter and he kept finding annoying not-comets that he didn’t want to distract him from his search. True, he added some questionable entries — M44, M45, and the double star M40 come to mind — but most of the objects on the list could easily be mistaken for comets.

So, should we really expect beginners to be excited about low-surface-brightness objects like M1, M33, M74, M88, or M101? By recommending the entire Messier list, we are indeed recommending many such objects. But I think we can do better. And that’s by starting off newbies with targets that are both easily found and clearly visible.

Don’t get me wrong; I’ve included a fair number of brighter Messier objects in my beginner’s deep-sky list, which appears later in this article. And those do serve as prime examples for beginners to try observing first, and then continue to check back in on, like revisiting old friends over the years. But even a list of the prime Messiers would leave out many other perfect deep-sky targets for beginners.

When I was a young amateur …

Certainly, back in the day, many of us amateurs learned persistence while tracking down whatever we could find with the telescopes available to us. And, driven by a love of the cosmos and lots of reading, I developed a good sense of what deep-sky objects to seek out. Additionally, I was in an astronomy club where more experienced members were ready and willing to mentor me. The sky was also darker then, so fainter deep-sky sights were easier to locate and view.

Today, you can find a slew of suggestions with a quick search on the internet. But like Forrest Gump’s box of chocolates, you never know what you’re going to get. Typically, it’s an off-the-cuff list of both good (high surface brightness, visually impressive) and terrible (low surface brightness, dim or invisible) objects supposedly for beginners. But they are often simply the favorites of the amateurs suggesting them.

1) The object must be within 8° — a typical finder scope field of view — of a magnitude 3.5 or brighter star to help beginners easily locate the target.

2) It should overlap as many bright stars as possible when viewed through a red dot (zero magnification) finderscope, as these are increasingly found on new telescopes popular with beginners.

3) It must have a high enough surface brightness to be well received through a small telescope, despite light pollution.

The first criterion is important because, despite the roughly 9,000 potentially naked-eye stars visible from Earth, the vast majority of those are rendered invisible by light pollution. Only around 280 stars are magnitude 3.5 or brighter. By choosing these stars as signposts, the search for beginner-friendly deep-sky objects can start with a naked-eye star visible in moderately to significantly light-polluted skies. This is essential for those using non-magnified finders (point two), which is often overlooked in online lists.

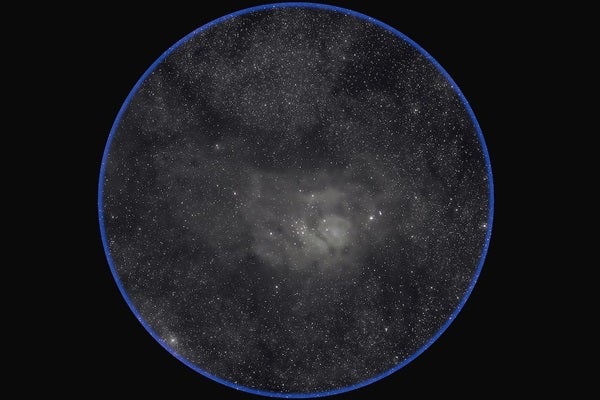

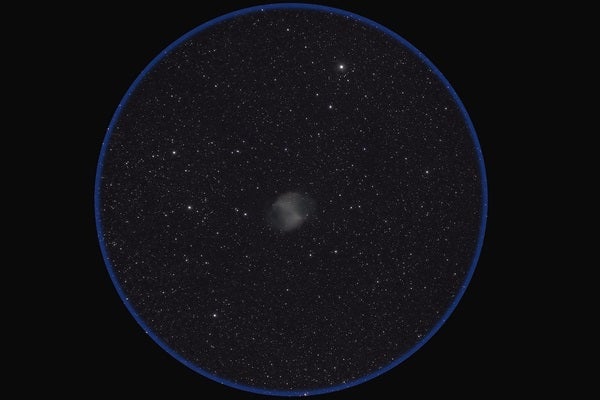

As for the third criterion, my past outreach experiences helped me identify what beginners were impressed with at the eyepiece. That’s why my list contains a good number of brilliant open clusters, a few impressive globulars, and some of the brightest nebulae. Galaxies often received the least enthusiasm from beginners, but I’ve sprinkled in a spiral and dwarf to ensure a bit of everything.

Seeing double

Importantly, there is an entire class of objects that we miss altogether if we only focus on the Messier, NGC, and IC galaxies, clusters, and nebulae: double stars. Such targets are great for amateurs, especially under light-polluted skies.

The problem with more expansive deep-sky objects is that, even if they are very bright, their brightness is spread over a large area, often resulting in relatively low surface brightness. This is not the case for double stars. They are pointlike, so there are no surface brightness issues to deal with — visibility is only a question of visual magnitude. Plus, multi-star systems litter the night sky. With so many colorful and interesting stellar duos and trios (and more) in reach of beginners, a thorough list must also include those.

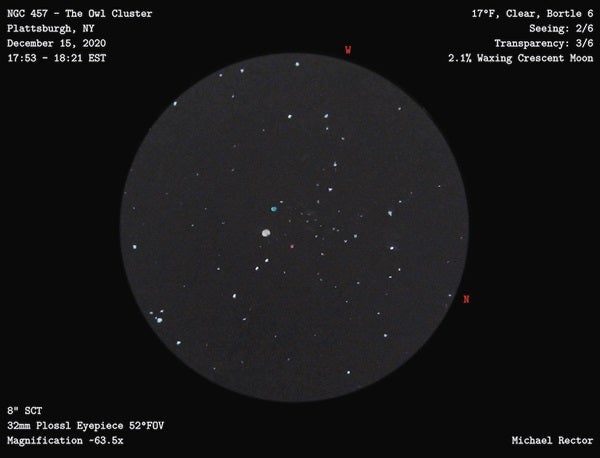

This compilation includes just 40 objects that are accessible to almost anyone. Such a relatively short list allows a beginner to enjoy multiple quick successes.

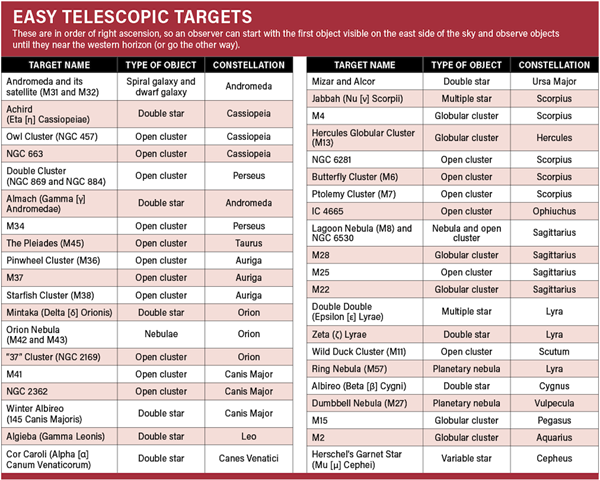

So, start to work your way through my official “Telescopes on the Sky” list, which includes 17 open clusters, 11 double or multiple stars, six globular clusters, four nebulae, two galaxies, and a lone variable star. You can also access the list at http://eyesonthesky.com/tutorials/telescopes-on-the-sky, where you’ll find further details on locating and observing each target.

Easy telescopic targets

I hope you feel the urge to share this new beginner’s list of deep-sky objects with your astronomically inclined friends. And, if you’re interested, consider joining me in advocating for darker nights. That won’t just help us all get a better night’s sleep, it will also help unlock views of the many beautiful distant objects that circle above our heads every night — most of which few beginners have had a chance to glimpse.

Keep your eyes on the sky and your outdoor lights aimed down. That way, we can all see what’s up!