But if you’ve never seen a Southern Hemisphere sky, you’ve never had the “Orion Nebula shock,” as I call it. That’s when you gaze up at M42 and then look over to the east and see the Carina Nebula rising. Much as we may love Orion, the Carina Nebula is factors larger and brighter, in a class by itself.

This past February, I had the great pleasure to accompany a group of Astronomy readers down to Costa Rica for our annual star party, which lets us see the wonders we can never glimpse from the North. We had a small but dedicated group of about 20 this year, all primed to observe the southern skies from a Star Lodge plantation camp north of Puntarenas, on the Gulf of Nicoya, near the country’s western edge. Costa Rica is a splendid place and our site offered an incredible natural adventure in addition to the sky, with daily walks to spy dozens of bird species, howler monkeys, crocodiles, and other critters. We swam, rode horses, and enjoyed the beauty of the locale, which is easy to getto — a mere three-hour flight from Miami.

Our 2020 trip was a joint venture with Astronomy’s travel partner, TravelQuest International. The endeavor was ably led by our maestro of logistics and organization, TravelQuest’s Cody Carter.

A new view

This year, we had the great fortune to raise the bar for our astronomical observing. I transported an Explore Scientific 16-inch Truss Tube Dobsonian telescope down to the site, outfitted with three of Scott Roberts’ gorgeous eyepieces. The 2″ 82° apparent field of view 30mm eyepiece, which we used the most for deep-sky objects, is a perfect eyepiece for the 16-inch, yielding views that were akin to peering into a huge porthole. If you’re looking for a transportable, large-aperture deep-sky scope, I highly recommend this instrument. It was a joy to use and gave me the best views of Southern Hemisphere treasures I’ve ever had.

The scope was remarkably easy to set up, and collimation, assisted by our HOTECH laser collimator, was similarly simple. Once we had the telescope assembled, I found that I could get it ready for the evening in about 20 minutes. And the views of myriad deep-space objects were mind-blowing.

Familiar favorites

In late February in Costa Rica, the darkening evening twilight brings on a sky shimmering with the bright stars of the winter Milky Way. The first thing we typically turned to was the Orion Nebula — always a show-stopper not only for our own guests, but for the local families and kids who came in one night to have what was, for many, their first view of the distant cosmos. The dark “fish’s mouth” near the nebula’s center, the bright stars of the Trapezium, and the winged shape of the glowing gas extending upward away from the nebula’s base were all apparent at low power, even without proper dark adaption. Our 16-inch Dobsonian showed bright deep-sky objects like M42 as almost photographic in their detail, simply lacking the faint portions visible in long-exposure images and the myriad colors human eye receptors are not structured to detect.

We also explored some other goodies in Orion, such as M78, one of the sky’s best reflection nebulae, which appears as a more-or-less circular haze surrounding bright stars. We next turned to the small, bright planetary nebula NGC 2022, a view of what our solar system may be like in 6 billion to 7 billion years. Near Orion, we wandered over to see two of the gems of Monoceros: the Rosette Nebula and the Cone Nebula.

The Rosette Nebula, a showpiece in astrophotos, is a wreath-shaped emission nebula with a pronounced central hole that contains a bright star cluster, NGC 2244. The nebula’s surface brightness is rather low; that is, individual parts of it appear rather dim, so it glows faintly as a circular, mottled haze. The bright star cluster stands out strongly, however, and the 16-inch scope revealed traces of the dark knots and nebulae intertwined with the bright gas — globules that are condensing down into stars. The Cone Nebula is a relatively easily visible prominent dark nebula, which lies near an associated star cluster, NGC 2264 — sometimes called the Christmas Tree Cluster because of its distinctive shape.

Next, we explored the vistas of Taurus. The central portion of this constellation, making up the Bull’s head, is the Hyades star cluster. At 151 light-years, it is one of the closest physically associated groups of stars to us. Aldebaran, the brightest star in the V-shaped group, is a red giant that lies in front of the cluster, 65 light-years away.

Seeking southern gems

All the other treats of the winter Milky Way were up there too, and high up, in a nicely dark sky. We waited until late evening, though, for the secret treats to rise — the far-southern gems we cannot see at all back at home. As wonderful as the Orion Nebula is, the Carina Nebula is far larger and brighter. Its three-pronged shape, separated into wedges by a broad dust band, gives it a glowing, spidery appearance in the big scope at low power, the field peppered with both bright and faint stars that show a range of color. The brightest star embedded within one of the wedges of nebulosity is Eta Carinae, one of the most massive stars known, and which has an enigmatic history. During much of the 19th century, it flared up to dazzling naked-eye brightness before fading to near its current magnitude.

Many other bright star clusters and some intriguing nebulae also live in the area. One of the greatest is the cluster IC 2602, sometimes called the Southern Pleiades, which is so bright and scattered, it’s astonishing that more people don’t know about it. If it were in the northern sky, it would be one of the most celebrated deep-sky objects of all.

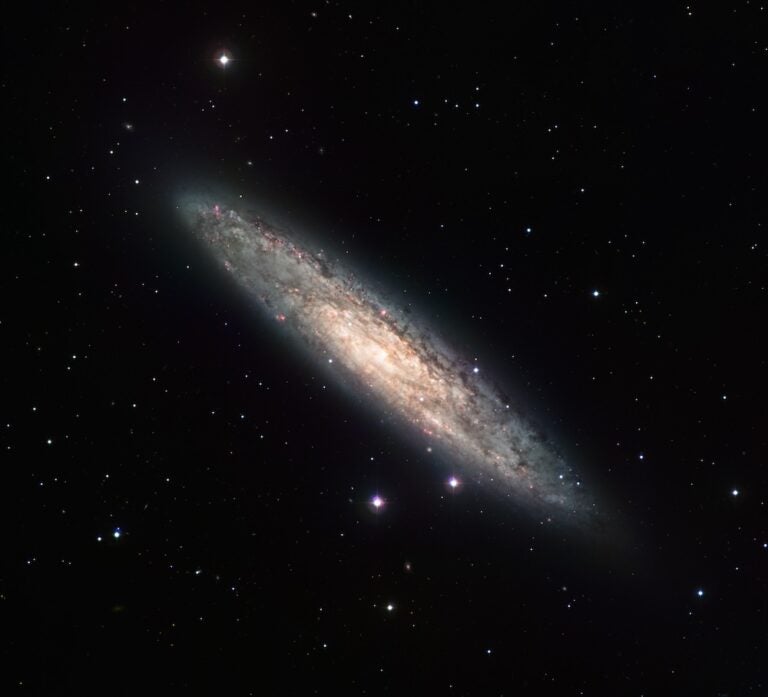

And that’s not all. There’s a huge panoply of great stuff that rises after midnight and into the early morning February skies. How about Omega Centauri, the largest and brightest globular cluster in the Milky Way? The view of this mighty sphere of stars in the 16-inch scope was truly jaw-dropping, as if we were viewing it from orbit around the cluster. A short distance north of Omega is the peculiar galaxy Centaurus A, a spectacular showpiece that perhaps foreshadows our own galaxy’s future. The result of a massive collision — two normal galaxies creating a huge, actively star-forming ball with a broad dark band — Centaurus A is astonishing, although somewhat shy with a low surface brightness. The same chaotic future lies ahead with the Milky Way and the Andromeda Galaxy when they merge.

Then, in the early morning hours, came another amazing treat. Most of us northerners are used to seeing the center of the galaxy, Sagittarius and Scorpius, relatively low on the horizon. But stay up long enough on our Costa Rica jaunt and you could see them high in the sky, their dozens of deep-sky treasures perched against inky blackness. The resulting telescopic views, especially in a big scope, were amazing. The Lagoon and Trifid nebulae, the Eagle and Omega nebulae, the Table of Scorpius with brilliant cluster NGC 6231, Scutum and its Wild Duck Cluster, the Bug Nebula, the Rho Ophiuchi region … the list goes on and on and on.

I can tell you that an expedition south to see the skies is one of the most memorable an amateur astronomer can take. We plan to journey once more to Costa Rica for deep-sky observing in February 2021, and again will use the 16-inch Explore Scientific Dobsonian we are so fortunate to now have. See the sidebar for complete details on how you can sign up for the adventure of a lifetime. Not only will the Carina Nebula, the Southern Cross, and Omega Centauri be waiting, but also howler monkeys, dozens of bird species, incredible forests, and many other natural wonders that will make the trip unforgettable. I look forward to traveling with you next year.