Transcript

The spring and summer of 2015 featured lots of evening planets, but as autumn begins, Venus, Mars, and Jupiter are prominent in the morning sky. Saturn, however, continues to look spectacular in the evening sky.

But September’s star attraction lies closer to home. The Moon takes center stage three times this month. In the first act, our satellite passes in front of 1st-magnitude Aldebaran — Taurus the Bull’s brightest star — before dawn September 5. Observers along a line that runs from the western shore of Lake Superior to Florida’s east coast will see the star emerge from behind the Last Quarter Moon’s dark limb as the pair rises. The farther north and east of this line you live, the higher the two objects will appear. From New York City, for example, they stand 11° above the eastern horizon when Aldebaran returns to view at 12:40 a.m. EDT.

The Moon passes in front of a much bigger and brighter star September 13. The target this time is the Sun, and Luna obscures part of it for people in southern Africa, southern Madagascar, and parts of the Indian Ocean and Antarctica. The best sites on land for this partial solar eclipse are around Cape Town, South Africa, where the event starts shortly before sunrise and peaks at 5h43m UT. The Moon then blocks 30 percent of the Sun’s surface area.

The Moon’s final and most impressive act arrives the night of September 27 and the morning of the 28th when it dives deep into Earth’s shadow to create a spectacular total lunar eclipse. Observers across most of North America will see all 72 minutes of totality the evening of the 27th. Viewers in most of Europe, Africa, and the Middle East will witness the eclipse before dawn on the 28th.

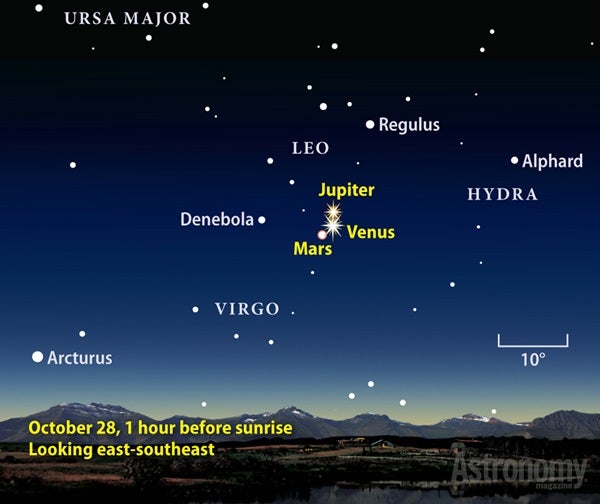

On October 1, Venus rises around 3:30 a.m. local daylight time followed by Mars just after 4 A.M. and then Jupiter a half-hour later. 17° separate the three in the predawn darkness.

As pretty as this morning scene is, however, it only gets better as the planets close in on one another. A great vista beckons October 28 when Mars and Jupiter appear 4.5° apart with Venus hanging between the two. This would be a great morning to set up your camera, fire away at a variety of different settings, and send your best results to readergallery@astronomy.com.

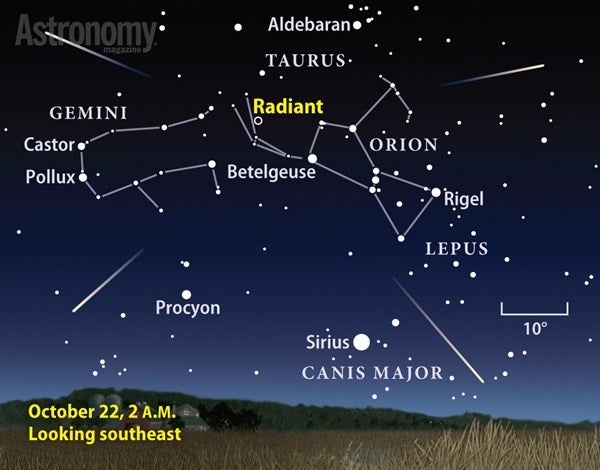

The Orionids peak this year the night of October 21 and the morning of the 22nd. The waxing gibbous Moon sets around 1:30 a.m. local daylight time, leaving four hours of dark skies for observers. The meteors appear to radiate from Orion the Hunter’s raised club, a region that climbs high in the south just before dawn. In its best years, the Orionids produce up to 70 meteors per hour, but astronomers predict 2015 rates lower than that.

The solar system puts on another meteor show in mid-November. At that time, Earth runs into debris ejected by Comet 55P/Tempel-Tuttle, giving us the Leonid meteor shower. The shower’s peak comes before dawn November 18. The Moon reaches its Last Quarter phase on that date, so it will rise around local midnight. After our satellite rises, simply face away from it to see the most meteors. If you can observe at a dark site far from city lights, you can expect to see up to 20 meteors per hour.

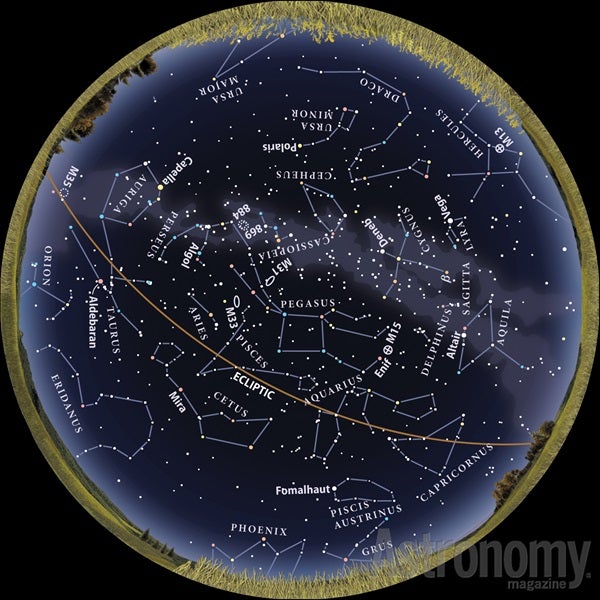

Each of the stars is the luminary in its constellation. Vega dominates Lyra the Harp, Deneb marks the tail of Cygnus the Swan, and Altair is the brightest star of Aquila the Eagle.

The Milky Way runs through the Summer Triangle, and if you follow its glow toward the northeast, you’ll come to the conspicuous constellation Cassiopeia the Queen. The constellation’s five brightest stars create a zigzag pattern that looks like the letter M on autumn evenings. The same stars resemble a W when Cassiopeia lies low in the north during springtime.

The W of Cassiopeia opens toward the most famous star in the sky: Polaris, the North Star. Easily visible from most locations, Polaris’ altitude equals the latitude at your observing site. The star also lies at the end of the handle of the Little Dipper, which is part of the constellation Ursa Minor the Bear Cub. Unless you view from a dark location, you won’t see all seven stars of the Little Dipper.

High in the sky throughout autumn, you’ll find a conspicuous group of four bright stars — the Great Square of Pegasus. The Square stands out because few stars show up inside it — from the suburbs, you’ll be lucky to see more than one.

Our final stop in the autumn sky is right next to Pegasus. Look for two graceful, curving lines of stars that radiate from the Square’s northeastern corner. In fact, that star is not part of the constellation Pegasus, although it does make one corner of the Great Square. It’s Alpheratz, the star marking the head of Andromeda the Princess.

The starry arcs represent Andromeda’s body. But enough about the constellation. Its main claim to fame is that it contains the biggest galaxy in our Local Group, and the brightest visible from most of the Northern Hemisphere. The Andromeda Galaxy, also known as M31, appears to the naked eye even from a suburban location. And from a dark location, it’s a stunning sight through binoculars.