As the name “Observing Basics” implies, this column is geared for the novice backyard astronomer, although some columns might benefit the intermediate or advanced skywatcher. This month, let’s go back to those basics (with some extras for more seasoned observers) as we look at the Little Dipper, aka Ursa Minor the Little Bear.

Many astronomical newbies have thought the striking dipper-shaped clutch of stars gracing the winter evening sky is the Little Dipper. It isn’t! They were tricked by a star cluster known as the Pleiades, or Seven Sisters, which is part of the constellation Taurus the Bull. The real Little Dipper is much larger, yet far less noticeable.

To find it, face north and look for the Big Dipper. Key in on two stars in the bowl, labeled Alpha (α) and Beta (β) on the Star Dome chart on pages 38 and 39. Trace an imaginary line from β through α and extend it five times that distance. That will bring you to the star Polaris, which marks the end of Little Dipper’s handle. Like its big brother, the Little Dipper is composed of seven stars, but four are too faint to be seen under skies brightened by light pollution or a Full Moon.

Polaris is the most notable star in Ursa Minor, and for good reason. Less than a degree from the North Celestial Pole, it serves as the guide for nighttime travelers trying to locate north. It’s also a navigator’s benchmark, as its altitude above the northern horizon provides a close approximation of northern latitude.

A closer look at Polaris through binoculars, a spotting scope, or a telescope rigged with a low-power, wide-field eyepiece shows that it’s part of a lopsided stellar ringlet. Ronald Stoyan and Stephan Schurig’s Interstellarum Deep Sky Atlas shows nine stars of 9th magnitude and brighter encircling an area about ¾º across. This asterism is known as the Engagement Ring. Polaris is the diamond, and the other stars trace a dented ring. Look for the Engagement Ring when skies are dark enough to see all seven Little Dipper stars.

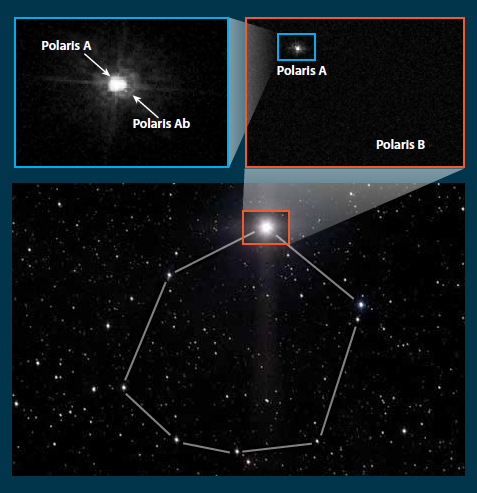

Polaris is a double star attended by an 8th-magnitude companion some 18″ away. The separation is reasonably wide as double stars go, but the six-magnitude difference in brightness between the two stars, dubbed Polaris A and Polaris B, makes the companion difficult to spot, especially with small-aperture telescopes. I’ve seen it with a 3-inch reflector at 60x. Richard Nugent of Framingham, Massachusetts, reports capturing it with a 10-inch reflector stopped down to a 40mm (1.6-inch) aperture with an off-axis mask. Magnifications of 37x and 74x did the trick.

Polaris B is an F3 spectral class star, slightly larger than the Sun. It lies some 240 billion miles (386 billion kilometers) from Polaris A, and a single orbit takes over 40,000 years to complete. Spectroscopic studies of Polaris A in 1929 revealed a much closer companion similar in mass and spectral type to Polaris B. Designated as Polaris Ab, it orbits the main star once every 30 years. So when you gaze upward at the North Star, you’re really looking at three stars that appear as one.

By the way, Polaris is the answer to our opening question. While it’s true that an actual orbit takes dozens of millennia, Polaris B does indeed appear to circle Polaris A once each day. This “orbit” results from the same earthly rotation that causes all stars to loop around the North Celestial Pole daily. This trick question was tossed my way a few years ago by astronomy writer/double star aficionado James Mullaney.

Questions, comments, or suggestions? Email me at gchaple@hotmail.com. Next month: Turning one telescope into two. Clear skies!