Key Takeaways:

For the sake of newbies who are just starting on this epic adventure of exploring the universe, let’s help whittle down the long process of deciding where to look. Our theme this month is the exquisite detail that, I guarantee, you’ll keep trying to observe.

For example, everyone enjoys watching Jupiter’s four big moons form a straight line with military band precision. As giant Ganymede circles back to its starting point once a week, Europa goes around exactly twice — to the second! And in that same interval, Io completes four revolutions, again with one-second accuracy. They’re bright, easy to see, and unique. And no other planet with satellites shares Jupiter’s lack of axial tilt. Jove’s poles angle a negligible 3° from vertical. And since its satellites orbit its equator, they must line up no matter where in their orbit they happen to be.

But first, a reminder that whatever cosmic wonder you’re after, optics alone aren’t enough. If someone gave you the keys to the two 6.5-meter Magellan Telescopes (along with the instruction booklet explaining how to detach all 30 cables from the echelle spectrograph and instead insert a nice 30mm visual eyepiece), you’d still need a night of good seeing, or atmospheric stillness. Fine detail always requires good seeing. Where I live, excellent seeing conditions arrive as often as magnetic pole reversals. But when they do come — heralded when stars are not twinkling in the least — we excitedly look for cool details.

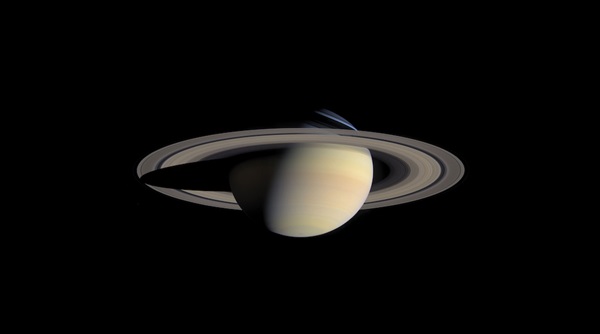

On Saturn, most observers seeking fine detail first try for the Cassini division. This inky gap between its A and B rings highlights the yawning breach separating the rings’ unique, epic beauty and their names, lazily derived from the alphabet. We often give things letters, like the six stars in M42’s stunning Trapezium and lunar craters around larger ones (Copernicus A, B, C, etc.). It’s not a bad idea, except where exceptional beauty cries out, unanswered, to try to stir a poet on the International Astronomical Union’s naming committee. As for that Cassini break, its impossibly narrow, half-arcsecond width somehow materializes whenever the air is steady. In the entire universe, no other thin dark line is more observed, sought after, or treasured.

You get the gist of my criteria. So, I’ll skip any further literary flourishes and simply list 10 examples of details telescopists try for when observing various celestial objects:

Let’s make it a contest — the winner gets to replace the names of Saturn’s A and B rings with more inspirational letters.