Winter skies often provide the clearest viewing of the year, but the cold temperatures that accompany them tend to keep stargazers huddled inside rather than bravely setting up their telescopes. If you find yourself in that boat, then binoculars may be your salvation. Pull them out of their case, step out your front door, and you’re ready to observe.

With that in mind, here are 10 of the season’s best binocular targets to tempt you outside on the next cold, clear night.

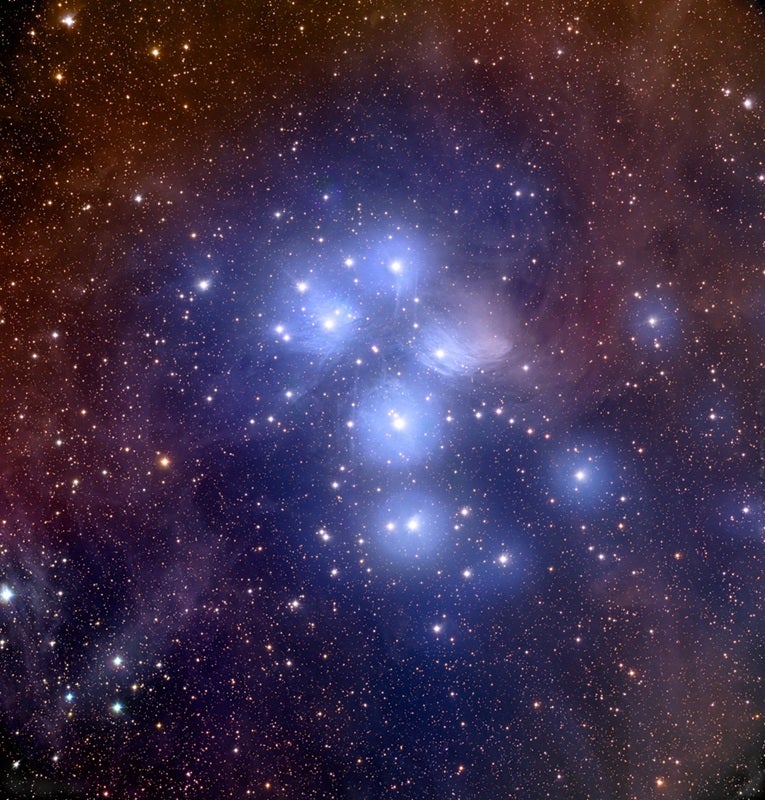

A family affair

Let’s begin with my favorite cluster, the Pleiades (M45) in Taurus the Bull. There may be only seven sisters here according to mythology, but binoculars show that they have many distant cousins. The brightest dozen or so Pleiads gleam like blue-white sapphires against a background sprinkled with diamond dust. Under dark, moonless skies, binoculars hint even at the faint tendrils of cosmic dust that engulf Merope, the southeastern star in the Pleiades’ “bowl.”

Only slightly related

In Greek mythology, the Hyades are half-sisters to the Pleiades, but in tonight’s sky, we see them as the V-shaped head of Taurus. Swing your binoculars their way and, like the Pleiades, the Hyades blossom into a striking sight. More than three dozen stars are visible through even the tiniest pocket binoculars, with many close pairs and trios. Orange Aldebaran (Alpha [α] Tauri), while not a true member of the Hyades, adds even more bling to an already spectacular target.

Near the Hunter

No single field of view crams in more action than the sword of Orion the Hunter. Drop some 4° straight down from Orion’s Belt and you will immediately notice the softly glowing iridescence of the Orion Nebula (M42). Look carefully, and this dim, shapeless blur transforms into what reminds me of a cupped hand. Can you spot the stars Theta1 (θ1) and Theta2 (θ2) Orionis buried inside? At 14x or more, Theta1 splits into the famous Trapezium star cluster.

The three stars in Orion’s Belt from south to north — Alnitak (Zeta [ζ] Orionis), Alnilam (Epsilon [ε] Orionis), and Mintaka (Delta [δ] Orionis) — team up with about 100 of their closest friends to form the open cluster Collinder 70. Sometimes called the Belt Cluster, it went unrecognized as a cluster until Swedish astronomer Per Collinder discovered in 1931 that its stars were all about the same distance from us and moving through space in the same general direction. These characteristics gave away its true identity. Collinder 70’s most distinctive feature is an S-shaped string of stars roughly 2° long that snakes between Alnilam and Mintaka.

Fit for celebration

Move about 3° south-southwest of Xi (ξ) Geminorum to find NGC 2264, which lies in the faint constellation Monoceros. This cluster is one of the brightest open clusters in the winter sky. Notice the pattern its stars create. Ten-power binoculars reveal that the cluster’s brightest suns form a wedge that reminds many observers of lights on a Christmas tree. The most luminous stars outline the tree’s profile while the brightest of those, 15 Monocerotis, marks the trunk.

A hint of color

Focus on the sky’s brightest star, Sirius (Alpha Canis Majoris), and then drop south about a field of view for our next port of call, open cluster M41 in Canis Major the Big Dog. A magnification of 7x will show about 20 faint points immersed in a misty patch of stardust. Double the magnification, and some of those stars will show subtle hints of yellow, orange, and red.

Stars gather in the Chariot

M38 is the first of three easy-to-see open clusters within Auriga the Charioteer. The trio passes near the zenith these evenings, so you’ll have to crane your neck to see them. A reclining lounge chair may make the effort easier. Look for the dim fog of M38 nearly centered in Auriga’s pentagonal body and about halfway between Theta and Iota (ι) Aurigae. Because the cluster’s brightest stars are just 8th magnitude, most binoculars will reveal only their soft combined glow.

Can you see a second clump of starlight just southeast of M38? That’s M36, a smaller, more condensed cluster that many observers find easier to spot. If you have a good eye and at least 63x binoculars, you just might see a few faint points peering back at you. Through my 25×100 giant binoculars, the brightest stars fall into a pattern resembling a crooked Y.

Move about a binocular field southeast of M36 to M37. With stars that shine no brighter than 9th magnitude, this cluster timidly reveals itself as a faint smudge through 50mm and smaller binoculars. Those that magnify 12x or more hint at a few dim specks of light.

The Twins’ realm

Our final winter target is M35, about 2° northwest of Eta (η) Geminorum, near the foot of Castor, one of the twins of Gemini. More than 200 stars make up this distant swarm, and at least two dozen are bright enough to be visible through 50mm binoculars from a dark site. The rest blend into a shapeless glow that even the naked eye can see on the clearest evenings.

The winter sky is beautiful through binoculars. Dress warmly and head outside to enjoy the view tonight. Before you know it, spring will be here, bringing warmer nights and another set of binocular favorites. Don’t let winter’s temperatures keep you from missing these treasures. And remember that two eyes are better than one.