Next, move from the Little Dipper to its larger counterpart. From Mizar (Zeta [ζ] Ursae Majoris), the middle star in the Big Dipper’s handle, follow a meandering line of four faint stars eastward. At the fourth star, hook a little to the northeast toward a diamond of four dimmer stars. Can you see a faint smudge next to the diamond’s eastern point? That’s the magnificent spiral galaxy M101. Often mistakenly called the Pinwheel Galaxy, M101 has no common name. (The real Pinwheel Galaxy is M33 in the constellation Triangulum.)

M101 has a low surface brightness, so you’ll probably need averted vision to see any hint of it. But isn’t it amazing that your binoculars can show you a system of billions of stars 21 million light-years away?

You’ll find another spiral galaxy — M106 — by continuing the line connecting Merak (Beta [β] Ursae Majoris) to Phecda (Gamma [γ] Ursae Majoris) along the bottom of the Big Dipper’s bowl. From Phecda, head about a binocular field of view farther east to a triangle made up of the 5th- and 6th-magnitude stars 3, 5, and 7 Canum Venaticorum (CVn).

M106 lies 1.7° south of 3 CVn, the star marking the triangle’s southern tip. The galaxy appears as an oval blur of light tilted south-southeast to north-northwest.

Now follow a zigzag line of stars 12° south of the triangle that marks Leo’s hindquarters to magnitude 5.0 Tau (τ) Leonis. Tau teams with the magnitude 6.6 star 8.5′ to its southeast to create a pretty double through binoculars.

Then, by placing Tau in the upper right (northwest) corner of your binocular field of view, you should spot not one, not two, but three more faint doubles. Add them together and you get an asterism that I call the Double Cross. None of the four pairs is a true physical binary, however, because all eight stars lie at different distances from Earth. But that doesn’t detract from their appearance through binoculars.

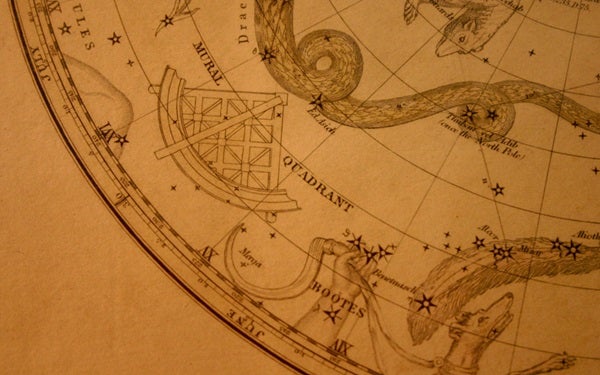

Head back north and, southeast of the Big Dipper, you’ll find the kite-shaped constellation Boötes the Herdsman. Nu (ν) Boötis, one of spring’s most striking double stars through binoculars, lies east-northeast of the kite’s top.

“Nu Boo” is made up of two colorful 5th-magnitude suns separated by 10′. The western star, dubbed Nu1, appears golden, while eastern Nu2 exudes a bluish tint. Their relationship is only an illusion, however. Nu1 is 840 light-years away, while Nu2 lies “only” 400 light-years from Earth.

Now look northeast of Nu Boo for the trapezoidal head of Draco the Dragon. About two binocular fields to the west, you’ll find a close-set pair of stellar headlights — 16 and 17 Draconis. The separation between them is 1.5′, with 17 being the northernmost of the two.

At magnitude 5.1, 17 is also slightly brighter than 16, which shines at magnitude 5.5. Unlike Nu Boo, 16/17 Draconis form a physical system. In fact, research shows that a close-set companion accompanies each component, making this a quadruple star.

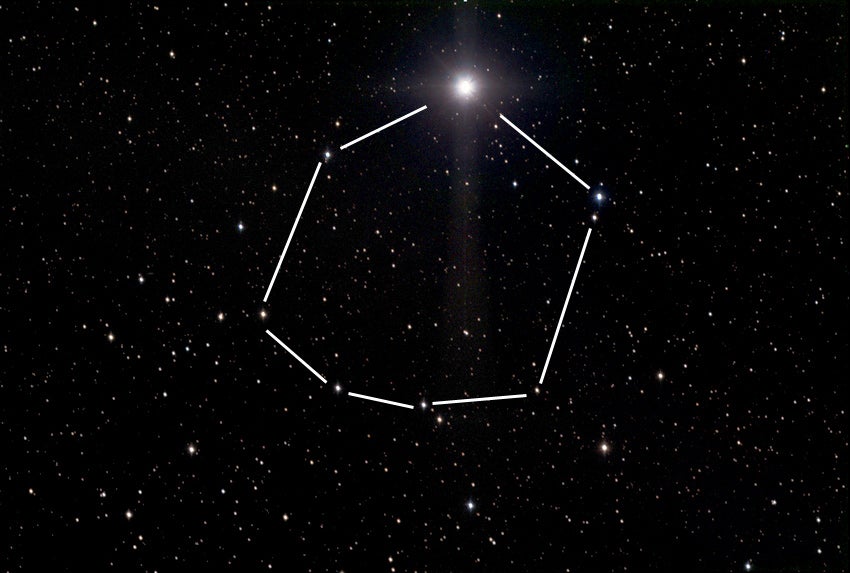

For my last target, I’ve chosen an object you may have to observe repeatedly to see. R Coronae Borealis, or “R Cor Bor” as it is affectionately known by amateur astronomers, is an intriguing variable star. You’ll find it 3.4° east-northeast of magnitude 2.2 Alphecca (Alpha Coronae Borealis). Typically, this yellow supergiant shines at about 6th magnitude, but every now and then it dips to 14th magnitude.

Most of these unannounced descents take just a few weeks to occur but last for several months or even years. Then, as unpredictably as it fades, R ascends back to its usual brightness. An obscuring carbon cloud belched from the star occasionally blocks its light, causing this odd behavior. As the cloud slowly dissipates, the star’s luminosity returns. See if you can catch R Cor Bor at its brightest.

With such a wide variety of targets this season, it’s easy to see that, when it comes to touring the spring sky, two eyes are always better than one.