This lack of knowledge underscores the critical need for wider and more-effective cultural outreach from the community of professional and amateur astronomers. Without it, public debate over fundamental issues of space-collision hazards and the strategies to mitigate those threats will remain mired in irrelevant earthly analogies and impressions from video games and Hollywood. Unless remedied, public and political support for rational preparation and countermeasures may be in doubt.

In the hours and days that followed the Chelyabinsk impact, as people tried to make sense of the fireball’s flight path, it became clear that only a handful of people were conceptually prepared for an event like this. Previous human experience with collisions — on land, on sea, and even in the air and orbital space — offered few insights into viscerally understanding the nature of such encounters. Although a few specialists had known about the physical theory for a long time, its implications hadn’t touched popular culture.

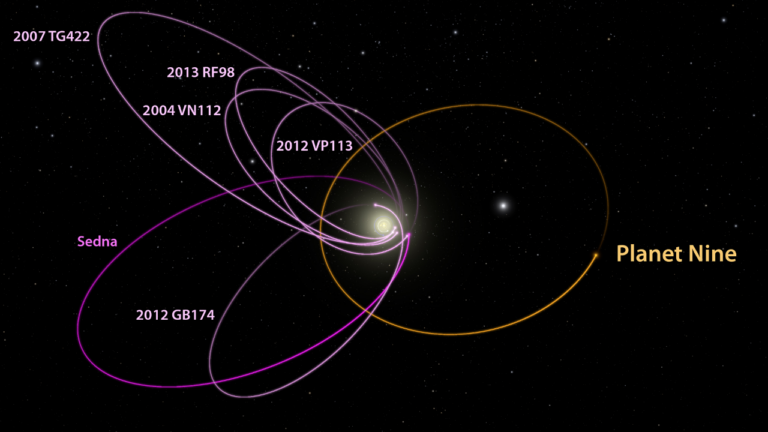

One common misconception assumes that Earth stands still in space where streams of rocks can be directed at it, like water from a hose. If one object comes close, other objects in the same stream might also come close, or even hit.

Related to this is the often-repeated notion that a historical impact such as Tunguska just missed Paris because if it had arrived several hours later, Earth would have rotated enough to move Paris into the firing line. Similar calculations this time had the Chelyabinsk impact hitting major cities either to the east or west. But astronomy-minded people know Earth isn’t a sitting duck, and that a time change of several hours would find our planet several hundred thousand miles along in its orbit and entirely out of harm’s way.

Understanding how a collision takes place is critical to planning ways of deflecting potential future impactors. People mired in a “fixed Earth” thought pattern likely will see the answer in deflecting the projectile to the side. But astronomy-minded people realize that any course alteration ought to be along the flight path, to make the potential impactor arrive at the orbital crossing point sooner or later than Earth does.

Another common misconception in news reports was the notion that if such events occur once in a century and the last such impact happened 105 years ago, then Chelyabinsk was our turn. The danger of a similar event would be greatly diminished for several decades, at least.

This fundamental fallacy assumes that the odds of a random event depend on previous occurrences of similar ones. Although this can be true for some processes, it’s a mistake to think that it is a common rule.

Instead, the chances of Earth being hit the day after Chelyabinsk were the same as they were the day before the impact — and the same as they were on the day of the impact. Like rolling a pair of fair dice, the odds have no memory of past trials. Earth doesn’t get a hot streak of impacts or near-impacts that is ever anything more than occasional random clusters.

Applying earthly analogies to explain this phenomenon to the public is natural, but we all need to be cautious to avoid metaphors that carry implicit, if unintentional, consequences. One can say we live in “a celestial falling-rock zone,” or that Earth wound up in “cosmic crossfire” February 15. Terms like these have a certain pithy punch for television or radio sound bites.

But space is literally, not just figuratively, unearthly. And trying to reach the public with oversimplifications or over-strained analogies may, after getting people’s attention, implant impressions that just aren’t accurate. That’s a recipe, on Earth or in space, for wrong solutions to genuine threats — and the reality of those threats is the authentic message of the awesome Chelyabinsk superbolide.