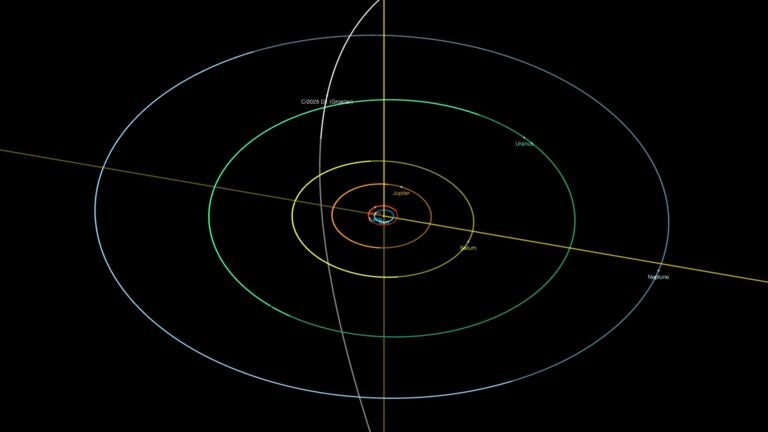

Yet not all is rosy with the lander, apparently — it last communicated with Rosetta two weeks ago (on July 9). Part of the problem appears to be in establishing a solid link between the two spacecraft. The task has become harder as the comet approaches the Sun and becomes more active, forcing mission controllers to move Rosetta farther from the nucleus and making communications between the two probes difficult. The comet’s activity should peak around its closest approach to the Sun, which arrives August 12/13.

ESA scientists hope to reestablish consistent contact with Philae so that it will be able to monitor the surface during this critical period. But in any case, Rosetta will continue its daring reconnaissance from above as scientists strive to learn more about these visitors from the solar system’s depths.

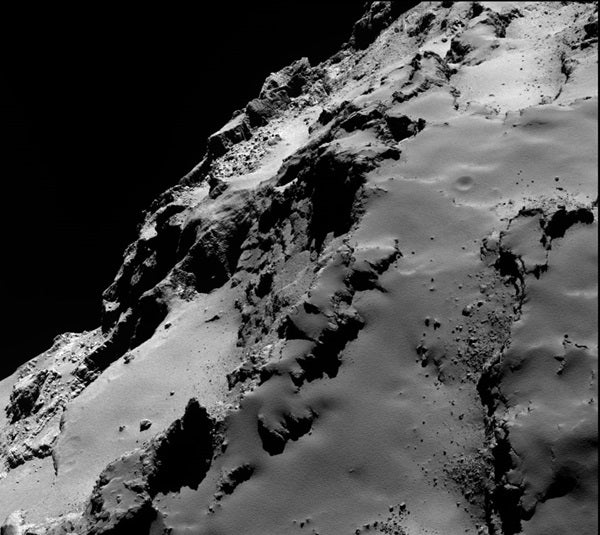

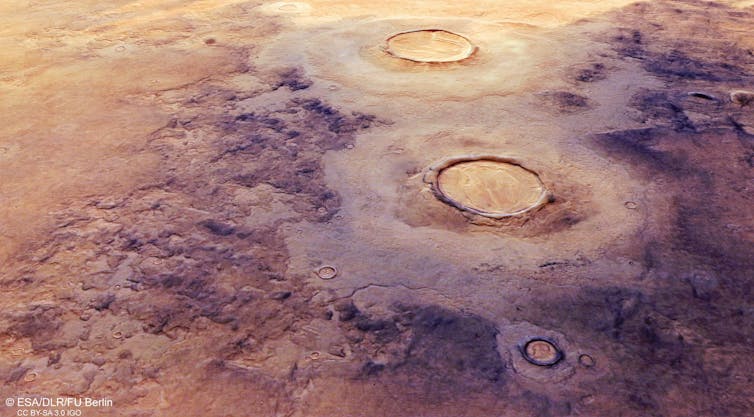

Here we present some of the best recently released images from Rosetta showing many incredible landforms on Comet 67P’s surface.