A glow undetectable to the human eye permeates the universe. This light is the remnant signature of the cosmic beginning — a dense, hot fireball that burst forth and created all mass, energy, and time. The primordial cosmic microwave background (CMB) radiation has since traveled some 13.8 billion years through the expanding cosmos to our telescopes on Earth and above it.

But the CMB isn’t just light. It holds within it an incredible wealth of knowledge that astronomers have been teasing out for the past few decades. “It’s the earliest view we have of the universe,” says Princeton University cosmologist Joanna Dunkley. “And it gives us so much information because all the things that we now see out in space — the galaxies, the clusters of galaxies — the very earliest seeds of those, we see in this CMB light.”

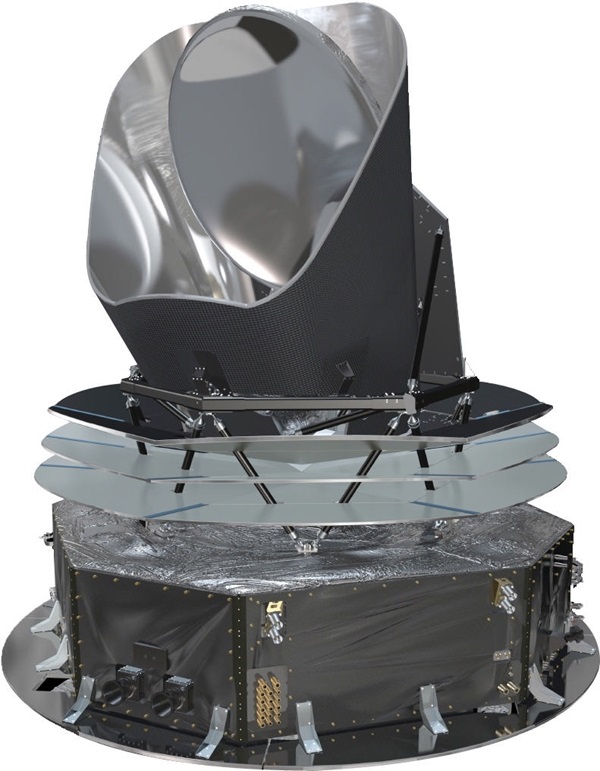

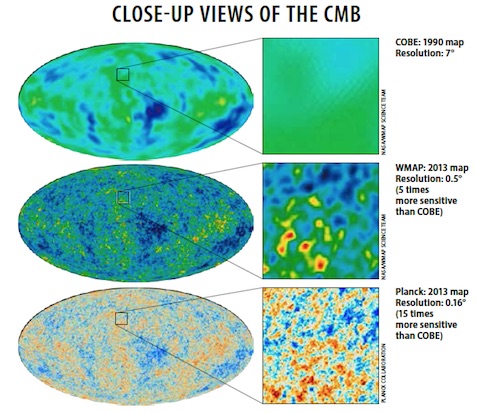

Extracting these clues from the CMB has taken multiple generations of telescopes on the ground, lofted into the atmosphere, and launched into space. In the mid-1960s, when Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson discovered the CMB’s pervasive microwave static across the sky, it appeared identical everywhere. It would take satellites launched above Earth’s obscuring atmosphere to map that microwave glow to precisions on the order of millionths of a degree. Specifically, three satellites — COBE, WMAP, and Planck — revealed that our current cosmos, which is complex and filled with clusters of galaxies, stars, planets, and black holes, evolved from a surprisingly simple early universe.

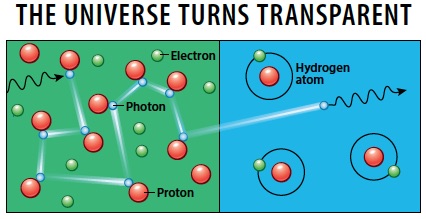

The universe began with the Big Bang 13.8 billion years ago as a fiery sea that expanded rapidly. A few minutes later, the universe’s constituent primordial subatomic particles glommed together into an elemental soup of atomic nuclei containing hydrogen, helium, and trace amounts of lithium. Electrons and light collided and scattered off of those atomic nuclei. Over the next thousands of years, the cosmos continued to expand, giving the particles more room to move and allowing the universe’s temperature to cool bit by bit. Around 380,000 years after the Big Bang, the temperature dropped to about 3,000 kelvins, cool enough for electrons to latch onto hydrogen nuclei. The universe became mostly neutral hydrogen, with some heavier elements swirled in.

With fewer individual particles zooming around, light could finally move about freely. And so it has traveled, mostly unhindered, in the approximately 13.8 billion years since that time of “last scattering.” These photons carry a snapshot of the 380,000-year-old universe.

Since the 1960s, telescopes on Earth have captured that glow in every direction of the sky. While the light 380,000 years into the universe’s history would have been visible to human eyes if we were around, cosmic expansion has since stretched the light into the longer wavelengths of microwaves — at least, that’s the wavelength astronomers had predicted. But would observations match theory?

The three probes

The Cosmic Background Explorer (COBE) launched in 1989. One of its instruments measured the intensity of the microwave glow at wavelengths ranging from 0.1 to 10 millimeters across the entire sky. The COBE science team’s first announcement, in 1990, was the result of that measurement. The radiation’s intensity plotted by wavelength makes it obvious that the CMB has a very specific intensity curve, where the strongest signal is at 2 mm. That wavelength corresponds to a temperature of 2.725 K. (The wavelength of light, and thus how much energy that light carries, is directly related to its temperature; redder light has less energy and a lower temperature than bluer light.)

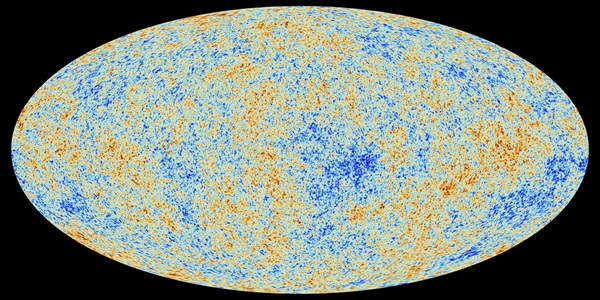

COBE’s other instrument broke apart the seemingly uniform 2.725 K glow into more detail, looking for spots where the temperature is warmer or colder than average. It turned out there is a difference of only a tiny fraction of a degree, about 0.00001 K, between hotter and colder spots.

But there is so much more that scientists can do with the CMB than confirm the Big Bang. “From the anisotropies, the hot and cold spots, we get the initial conditions — how bumpy was the early universe and also what is its composition,” says Mather.

The next CMB satellite was designed to improve upon these anisotropy measurements, mapping them at finer angular resolutions. COBE could map hot and cold spots of about 7° on the sky, while the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP), launched in 2001 and operated until 2010, could zoom in to a resolution of better than 0.5°. Planck, the CMB satellite that operated from 2009 to 2013, zoomed in even further, to 0.16°.

All of these missions mapped temperatures to the order of 0.00001 to 0.000001 K. To minimize measurement errors related to such small signals, the spacecrafts’ detectors pointed toward two spots on the sky at the same time and measured the temperature difference between them. The satellites swept the entire sky in this fashion, and software generated a map of all those tiny differences. That map holds a treasure-trove of cosmic secrets.

To reveal those secrets, cosmologists study the pattern of hot and cold spots frozen into the CMB and decompose those spots into their constituent sizes. While most of the hot and cold spots are about 1° on the sky, they are overlaid on fluctuations with larger sizes.

“Imagine looking at a smooth pond of water that we might drop pebbles into,” says Dunkley. “If you drop a whole bunch of pebbles in, the ripples will sort of combine together, and you see a whole pattern of ripples across the water. We think of this pattern of slightly different temperatures of this light on the sky a little bit like the pond after it’s covered in ripples.”

The size breakdown of the CMB’s temperature spots, or fluctuations, is like a cosmic Rosetta Stone. The strength of the fluctuations’ signals at different scales is associated with the universe’s age, its ingredients, its expansion rate, and when the first stars lit up the cosmos. By comparing computer models to the signal strengths (which astronomers obtained from analyzing WMAP and Planck data), researchers can piece together what the early universe looked like and how it has evolved.

Thanks to these three cosmic probes, we know the universe began in a Big Bang, and around 380,000 years later, electrons and protons combined, letting light roam free. We know our cosmos is 13.8 billion years old and how fast it is expanding. We know that 31 percent of the universe is matter, but only 5 percent is made of ordinary matter like you and me, while 26 percent is invisible dark matter. Much more of the cosmos is composed of a mysterious, repulsive dark energy — 69 percent.

And perhaps most importantly, astronomers now have a way to find out pieces of information not literally encoded in the CMB itself. That’s because the CMB maps and their statistics have led to the so-called standard model of cosmology.

“We now have a really simple model that describes basically all of our observations,” says Dunkley. “We can track from the very first moments of time all the way through today and make predictions about how large-scale structure evolved. And it has remarkable success. That’s the big thing these satellite missions have given the community.”