NASA launched two Orbiting Astronomical Observatories in 1968 and 1972. Both produced a wealth of information, and support for a space telescope grew. But it was the space shuttle, with its capacity to deliver and service large payloads, that finally made the concept feasible.

NASA selected a team of scientists in 1973 to establish the basic design of such a telescope and its instruments. Funding issues cut the proposed mirror diameter and also prompted collaboration with the European Space Agency (ESA), which joined the project in 1975. But at last, the project began.

What’s in a name?

When NASA secured funding for the space telescope, the agency decided to name it after Edwin Powell Hubble, whose studies expanded the universe beyond our galaxy.

Hubble conclusively proved spiral “nebulae” were galaxies like the Milky Way. And he, along with Milton L. Humason, discovered that galaxies’ distances are proportional to their redshifts (the speeds at which they are moving away from us). Now known as Hubble’s law, it marked the first observational support for the Big Bang theory.

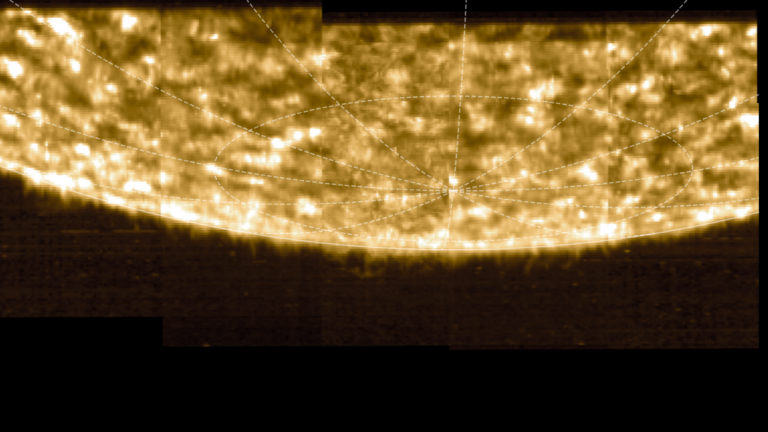

For the telescope, the mirror and optical systems were the most crucial parts. Telescopes typically have mirrors polished to an accuracy of about 1/10 the wavelength of visible light. Because Hubble would observe from near-ultraviolet to near-infrared wavelengths, its mirror needed to be polished to an accuracy twice as good.

Hubble has a 94.5-inch (2.4 meter) mirror. The wavelengths Hubble can “see” range from 115 to 1,000 nanometers. Visible light’s range is 400 to 700 nm.

Building the space telescope was a painstaking process that spanned almost a decade. Contractors actually finished the mirror in 1981 and then completed the optical assembly in 1984. Although the science instruments arrived at NASA, ready to go, in 1983, it took engineers until 1985 to complete assembly of the entire spacecraft.

NASA originally scheduled the launch for 1986 but was forced to delay it after the Challenger accident. Space shuttle Discovery finally carried the Hubble Space Telescope into orbit on April 24, 1990.

Hubble’s instruments

When launched, Hubble carried five scientific instruments. All have since been replaced. The Wide Field and Planetary Camera (WFPC) is a high-resolution imager. This instrument, and its subsequent replacements, are the ones best known to Astronomy readers — it’s these, after all, that produce the majority of the spectacular images we enjoy.

The Goddard High Resolution Spectrograph, the Faint Object Camera, and the Faint Object Spectrograph all operate in the ultraviolet range of the spectrum. The High Speed Photometer conducts observations of objects that vary in brightness. It can take up to 100,000 measurements per second with a measuring accuracy better than 2 percent.

Hubble’s three Fine Guidance Sensors keep the telescope accurately pointed during observations. Power comes from two solar panels, which also charge six batteries that keep things going during the roughly 25 minutes per orbit that Hubble spends in Earth’s shadow.

On June 25, 1990, astronomers learned that the space telescope’s images were out of focus. Why? The main mirror had been ground to the wrong shape! Fortunately, because engineers knew what went wrong, they were able to design new optical components with the same error but reversed.

And the upgrades continued. In 1997, astronauts replaced instruments, repaired thermal insulation, and boosted Hubble’s orbit. In 1999, a different group replaced all six gyroscopes, a Fine Guidance Sensor, and thermal-insulation blankets. March 2002 saw the installation of a new main camera. During this mission, astronauts also replaced the solar arrays with new ones two-thirds as large that provided 30 percent more power.

Best. Telescope. Ever.

What really sets Hubble apart, however, is the astounding research scientists have conducted with it. The pictures are nice (and some even important), but let’s face it: The images Hubble has produced are the icing on the cake. Astronomers know it’s Hubble’s data that rocks our universe. Need proof?

In December 1995, the Hubble mission team pointed the telescope toward a small spot in the constellation Ursa Major. Earthbound telescopes showed nothing there. But after 342 exposures over 10 days, the resulting image — the Hubble Deep Field — shocked the world. It contained some 3,000 objects, nearly all distant, previously invisible galaxies. This and subsequent “deep field” images have revealed far more galaxies than astronomers thought existed, including some that existed when the universe was less than a billion years old.

In January 1999, Hubble imaged what was, up to that time, the most powerful explosion ever recorded. This optical counterpart to a massive gamma-ray burst identified the host galaxy and the cause: the collapse of a stellar core due to a supernova explosion.

Also in 1999, astronomers using Hubble completed an eight-year survey of Cepheid variable stars, those whose periods correspond to their real brightnesses. The results revealed that the Hubble constant — the expansion rate of the universe — is 70 kilometers per second per megaparsec, a number within 5 percent of the current value.

Hubble observations also helped determine that quasars are powered by supermassive black holes. As matter falls into one, the surrounding region heats up and releases tremendous amounts of energy and light. In addition, Hubble found that almost all galaxies with bright, active centers have supermassive black holes feeding off the galaxy’s matter.

In the mid-1990s, astronomers discovered that a mysterious force they dubbed “dark energy” was causing the universe’s speed of expansion to increase. Hubble added to the precision of this measurement in 2016 when it collected data that showed the universe was expanding 5 to 9 percent faster than predicted, with an error of only 2.4 percent.

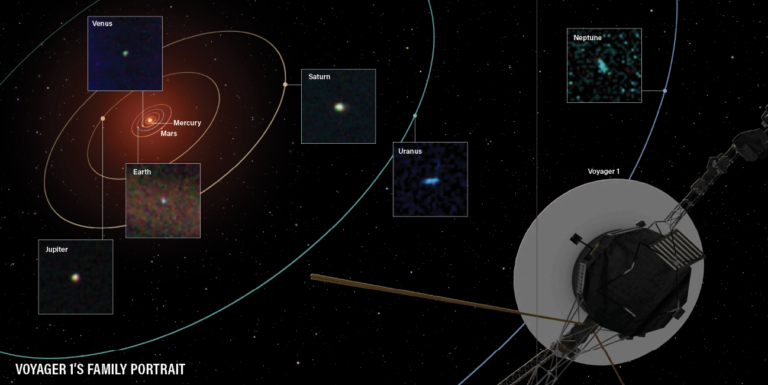

Closer to home, Hubble has tracked changes in the atmospheres of the outer planets, discovered four of Pluto’s five known moons, recorded huge auroral displays on Jupiter and Saturn, documented the impact of Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 as it hit Jupiter, and more. And, to be clear, it’s not done yet.

Think of each of the images accompanying this story as a sight that early astronomers like Galileo could not have even dreamed up. Hubble’s 28-year success story has made it a household word — indeed, a pop culture icon. Besides being the greatest telescope ever built, Hubble may be the single greatest technological achievement of all time. It not only influenced scores of astronomers, but a generation of everyday folk as well.

Because of Hubble, millions of people consistently turn their thoughts heavenward and contemplate our universe’s beauty and unimaginable vastness.