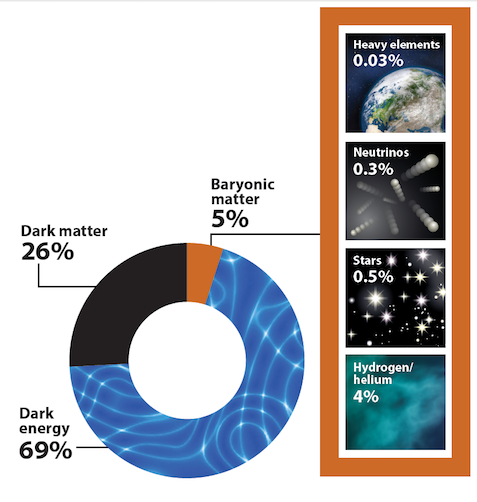

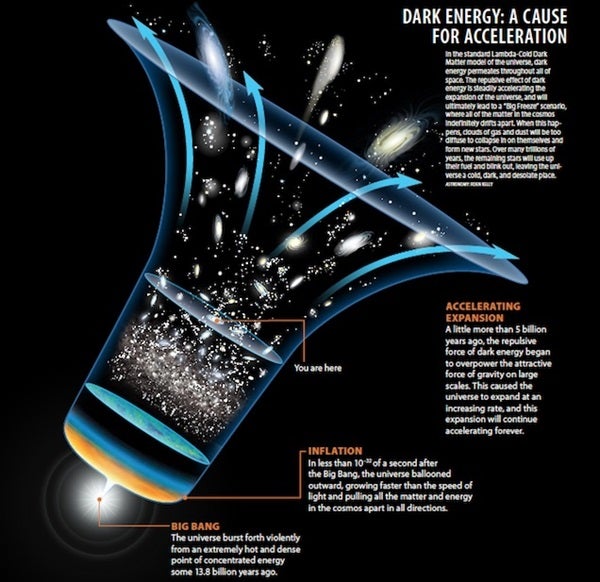

This means that the explosions were farther from us than theory predicted; while theory already took into account our knowledge that the universe is expanding, this discovery indicated it is expanding at an increasing rate. But the matter we knew about in the universe — galaxies of stars and gas, called normal matter, plus invisible dark matter — works by pulling, and therefore something had to be pushing everything apart. That something, which astronomers now call dark energy, is a repulsive force, and it also happens to make up more of the universe than normal and dark matter combined.

Discovering dark energy

To reveal this mysterious energy, scientists studied type Ia supernovae, all of which have light-intensity curves with very similar shapes. How these blasts’ brightness changes over time — becoming brighter then fading — follows a specific shape that’s always nearly the same. Astronomers can therefore compare and standardize these curves, providing a tool to study the distant cosmos.

The curves have the same shape because they start with the same type of source: a densely packed star remnant made of carbon and oxygen. That remnant — a white dwarf — lives in a binary system with a companion star. Over time, the white dwarf siphons gas from its companion, and that material builds up on the surface. The white dwarf’s mass increases until it reaches a point where it undergoes a runaway nuclear reaction, and the star explodes. Astronomers know how much energy a type Ia supernova gives off during a blast, so the observed brightness gives them that supernova’s distance.

In the late 1980s, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory astronomer Saul Perlmutter created the Supernova Cosmology Project to use these blasts to track how our universe is expanding. In 1994, astronomer Brian Schmidt, who’s been at Australian National University since 1995, co-launched a competing group, the High-Z Supernova Search Team. Then in September 1998, Schmidt’s team published a paper analyzing 16 type Ia supernovae; in June 1999, Perlmutter’s team published their analysis of 42 type Ia supernovae. Both groups found that more distant stellar blasts are fainter than they should be if cosmic expansion is slowing down — which is what astronomers’ previous model of the universe had predicted. Instead, it appeared the universe’s expansion is speeding up. It seemed that for the cosmos to do what the observations showed, only about 25 to 30 percent of our universe could be matter, which gravitationally pulls on other material.

“We have all of human experience telling us that gravity pulls things together,” says David Weinberg, a cosmologist from The Ohio State University who has been studying the large-scale structure and evolution of the universe for more than 30 years. Yet if our cosmos is accelerating, something else is at play. “That either means that there’s some new component of the universe with exotic physical properties, or that Einstein’s theory of gravity is incorrect.” Most astronomers are more convinced it’s the former: Some weird newly found component, which they’ve nicknamed dark energy, is acting against gravity.

Perlmutter and Schmidt won the 2011 Nobel Prize in Physics for their groundbreaking work, along with Adam Riess, who led the High-Z Supernova Search Team’s analysis. The discovery of accelerating expansion was hailed as the discovery of the decade.

This discovery wasn’t the only reason the paradigm shifted so easily. “Those were certainly important experiments,” says Weinberg, but there was another reason they were adopted as fact relatively quickly: “They were landing on well-prepared ground.” The work of Perlmutter, Schmidt, and Riess was the culmination of a decade of research slowly uncovering clues to an accelerating universe, and they provided a way to solve several cosmic mysteries.

Perhaps the most concerning of those mysteries involved the universe’s age. If the universe were made only of matter, it would have decelerated since the Big Bang due to the gravity of all that matter pulling on itself.

“If it had been slowing down over its entire history, then its age, [astronomers] calculated, would be about 9 or 10 billion years old,” says University of Queensland cosmologist Tamara Davis. However, stellar astronomers were finding stars that appeared to be 13 billion years old. “So we had a situation where the oldest stars were older than the entire universe,” says Davis, which was a bit of an alarming mystery. However, when the researchers incorporated the fact that the universal expansion is accelerating and not decelerating, the age discrepancy somewhat disappeared. Perlmutter’s group calculated a 14.9 billion-year-old cosmos, and Schmidt and Riess calculated a 14.2 billion-year-old one. Today, scientists know from a variety of studies that the universe is 13.8 billion years old.

So what could dark energy be? The leading theory is vacuum energy, also known as the cosmological constant, which is basically the idea that empty space is not actually empty.

“Even if you take all of the matter out of space, the light, any neutrino, any particles whatsoever, in complete nothingness, you’re never left with complete nothingness,” says Davis. What’s left, according to quantum physics, are virtual particles, which pop in and out of existence. Because these last for short amounts of time, they don’t actually violate conservation of energy, adds Davis. And these virtual particles, which are effectively manifestations of the time-energy uncertainty principle in a vacuum, would create a type of negative pressure — they push instead of pull.

But there’s a problem with the cosmological constant as the dark energy candidate: It’s not strong enough. Quantum mechanics predicts a vacuum energy density (the “weight” of empty space) that is 10 followed by 120 zeroes more than cosmologists observe. “I’m pretty confident in saying that’s the worst ever match between a theoretical prediction and observation,” says Davis, laughing.

While scientists are much more confident 20 years after dark energy’s discovery that it does in fact exist, they clearly haven’t identified it yet. But despite this, the field is still progressing, even though scientists don’t yet understand the majority of what makes up the universe.

Weinberg isn’t fazed. “I have some history of living through big questions about the nature of dark matter, and actually finding resolution of them,” he says. “So that leaves me optimistic for the future.”