Key Takeaways:

Apollo’s legacy extends to the naming of several lunar features. Craters honor many of the Apollo astronauts, and Mount Marilyn — named for astronaut Jim Lovell’s wife — served as a key navigational landmark during the first Moon landing. Remarkably, this recently named mountain is one of only a few lunar features that carry a woman’s name.

It’s a man’s world

Explorers, at least since Odysseus, have struggled between the urge to forge ahead toward new discoveries and to return to family and friends. You might expect this longing for home would inspire them to name newly found lands after their distant loved ones. You’d be wrong.

Christopher Columbus didn’t name anything after his wife, Filipa Moniz Perestrelo. Neither Ferdinand Magellan (whose wife was Beatriz) nor Captain James Cook (Elizabeth Batts) honored their wives with the names of faraway countries. Walter Raleigh did name Virginia after a woman, but it was his royal patroness, Elizabeth I of England, often referred to as the “Virgin Queen.” Sadly, for every million people who have heard of these explorers, perhaps only one knows the name of any of their wives.

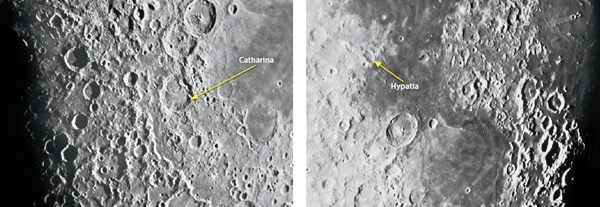

Of the two women he honored, Saint Catharine of Alexandria got the bigger prize. Catharina is an imposing crater that adjoins Cyrillus and Theophilus in an impressive chain. A much-revered Christian martyr, Saint Catharine, alas, apparently never existed. Her legend seems to be based on that of Hypatia of Alexandria — a Neoplatonist philosopher, astronomer, and mathematician — and the second woman Riccioli honored. Hypatia Crater is less than half the size of Catharina and far less prominent.

The lack of women on Riccioli’s map largely reflects the subordinate roles they played in Greco-Roman and Christian societies, and the fact that women were generally dissuaded from scholarly endeavors. It may also reflect the reality that many scholars were priests or bachelors. According to the late English astronomy popularizer Patrick Moore, French philosopher René Descartes claimed that named lunar craters are inhabited by the spirits of their namesakes. Had what Descartes said been true, the Moon would have been as singularly lacking in female company as the Monastery of Mount Athos.

Shakespeare wrote in the Moon-enchanted A Midsummer Night’s Dream, “The course of true love never did run smooth”; this has been even truer on the Moon’s rugged surface. Astronomers wanting to immortalize their loved ones sometimes had to disguise their purposes. A case in point: On the map of the Moon compiled at the Paris Observatory under the direction of Jean Dominique Cassini, a woman’s face in profile projects from the mountainous Promontorium Heraclides into the smooth bay of Sinus Iridum. Through a telescope at low power, this feature appears striking when it lies on the terminator, but under higher magnification, it disappears into a miscellany of hills and ridges.

A ladies club starts to form

As more women gained recognition for their scientific aptitude and accomplishments, selenographers bestowed their names on lunar craters. Still, women remained a distinct minority. Among those honored were redoubtable 18th- and 19th-century figures such as Nicole-Reine Lepaute, Mary Somerville, and Caroline Herschel (whose crater, C. Herschel, is much less distinguished than that given to her brother William).

More recently, women honored on the Moon include Maria Mitchell and several of the human “computers” who analyzed photographic plates at the Harvard College Observatory: Wilhelmina Fleming, Antonia Maury, Annie Jump Cannon, and Henrietta Swan Leavitt. Marie Curie, the first double Nobel laureate, was honored with her maiden name, Sklodowska, nine years before her husband, Pierre, got his own crater.

The first woman in space, Russian cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova, is the only one officially honored while alive — she’s still going strong in early 2019. In the latest count of the more than 1,600 craters on the Moon, only about 30 bear a woman’s name. Part of this reflects stringent rules set by the International Astronomical Union (IAU), the governing body for naming features on the Moon and other planetary bodies. The rules were adopted to prevent solar system nomenclature from becoming utterly chaotic and capricious. But it also, no doubt, exposes the long-standing sexism and discouragement of women in mathematics and science in Western culture.

Though generally (and in view of past abuses, not unreasonably) strict about adopting the names of people still alive, the IAU has overlooked this rule on occasion. Tereshkova is a prime example, and several Apollo astronauts also have been honored. Other exceptions have sneaked in because only insiders knew their back stories. For example, American mappers in 1976 named a small lunar crater “Kira” in tribute to the eminently worthy Kira Shingareva, principal scientist at the Planetary Cartography Laboratory at the Space Research Institute in Moscow.

Against this background of the IAU insisting on the integrity of lunar nomenclature, we come to what is undoubtedly the most interesting feature from the Apollo era to receive a personal name: Mount Marilyn. It doubles as the only Apollo landmark visible to earthbound observers through binoculars or a small telescope.

We are now 50 years removed from the historic Apollo 8 mission, in which astronauts Frank Borman, Jim Lovell, and Bill Anders first circumnavigated the Moon. Though often overlooked in favor of Apollo 11’s lunar landing in July 1969, the December 1968 flight of Apollo 8 was probably more significant — and certainly more radical. As the first manned mission to leave Earth orbit and reach the Moon’s sphere of gravitational influence, it accomplished a truly astronomical leap forward in distance. It would be as if the Wright brothers, after their first successful flight at Kitty Hawk, immediately set out to fly around the globe.

Above all, Apollo 8 raised the consciousness of people back home through that ravishing color image of a beautiful blue Earth rising over a desolate Moon. Anders took the “Earthrise” shot on Christmas Eve during the third of 10 orbits around the Moon. It gave us a cosmic perspective on our home planet, revealing the precious jewel in all its beauty, fragility, and finiteness. The photo even helped accelerate the environmental movement.

It surprises many people that this was not the first image of Earth from the vicinity of the Moon. Lunar Orbiter 1 captured a similar view in August 1966, though it was a black-and-white image that lacked the contrast — and impact — of a blue Earth above the gray Moon set against the stark blackness of space. It also mattered that a robot took the earlier image whereas a human took the second. The astronauts saw the scene with their own eyes, reacted to it, and snapped the picture.

Although Apollo 8 accomplished many firsts, it also was a trailblazer for Apollo 11. To fulfill President John F. Kennedy’s audacious goal of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to Earth by the end of the decade, Apollo 11 astronauts needed Apollo 8 to serve as a scout. One important task was to locate suitable landmarks along the approach to the prospective landing site in the Sea of Tranquillity.

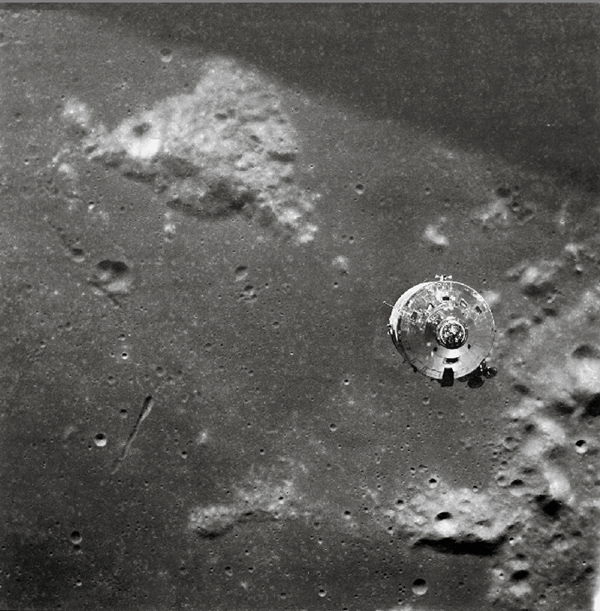

Lovell’s job was to study the lunar surface with an eye toward navigation. On Apollo 8’s second orbit around the Moon, Lovell looked down on craters that he described as resembling what pickaxes make when they strike concrete. Passing toward the Sea of Tranquillity, he took note of the crater Taruntius, then of the low ridges near the northwestern edge of the Sea of Fertility. The range, known as Montes Secchi, grazes Secchi Crater, named for Jesuit astronomer Angelo Secchi.

Mike Collins, at ground control, replied, “Roger.”

Despite Collins’ affirmative, no selenographer would have recognized the name. Lovell already had identified this triangularly shaped mountain — officially known at the time as Secchi Theta — as a significant navigational landmark from a Lunar Orbiter scout image even before he had lifted off for the Moon. (It seems rather strange now, when GPS can get us from here to there with little effort on our part, but one really did rely on printed maps to land on the Moon in those days.)

Lovell decided to name the feature after the one person whose support was most indispensable to his own success — his wife, Marilyn. Chivalry was not yet dead. Indeed, in naming this feature for his wife, Lovell showed more chivalry than had the great explorers of the 15th and 16th centuries.

A long time coming

The triangular mountain would always be Mount Marilyn to Lovell, and so it was to the astronauts of Apollo 10. During that May 1969 mission, the lunar module descended to within 8.9 miles (14.3 kilometers) of the surface. On a later orbit of the Moon, the crew saw the feature out the window. “We’ve just passed over Mount Marilyn and the crater Weatherford. Over,” intoned Commander Tom Stafford upon reaching the point where the next mission would ignite the lunar module’s engine to slow down the craft and begin the descent toward the lunar surface.

When the real thing took place on Apollo 11 in July 1969, Mount Marilyn again pointed the way:

Buzz Aldrin: “We’re going over Mount Marilyn at the present time, and it’s ignition point.”

CapCom [Bruce McCandless]: “Roger. Thank you. And our preliminary tracking data for the first few minutes shows you in a 61.6 by 169.5 orbit. Over.”

Aldrin: “Roger.”

CapCom: “And Jim [Lovell] is smiling.”

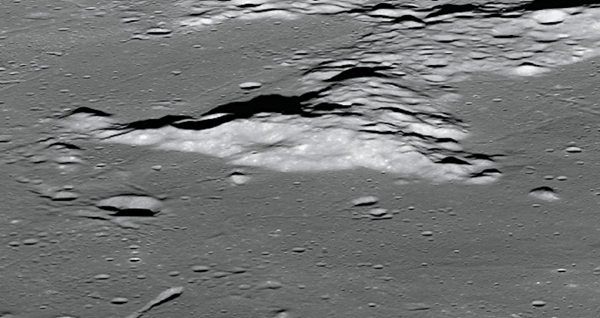

Oddly, Mount Marilyn long remained an unofficial name — despite, as Lovell told one of us, “representing a significant event in the history of spaceflight. It was the initial point where Apollo 11 started its descent into the Sea of Tranquillity. It is the only visible icon to represent that historical feat.”

In fact, starting in 1973, it became something of an orphan — a feature without a name. Not only was that the last year the IAU sanctioned the names of craters for still-living individuals, but it was also when the group abandoned a long-standing precedent of designating topographic prominences around named features. Thus, even Secchi Theta was wiped from the map. Instead, the mountain that had played such a crucial role in the history of manned lunar exploration was officially just one of the peaks in Montes Secchi.

A long and sometimes bitter political battle ensued between those wanting to see Mount Marilyn adopted and the IAU. Despite how unpopular the stance proved to be, the IAU steadfastly rejected the name chiefly on the grounds that the name Marilyn was commemorative and that it was associated with a living person.

But supporters did not give up, and after repeated attempts, the IAU finally changed its mind. On July 26, 2017, the organization decided that the name was appropriate after all. It was not meant to commemorate a specific person (Marilyn Lovell, Marilyn Monroe, or anyone else). It merely assigned a female first name to the feature. The IAU’s Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature lists the origin of the name as simply “Astronaut named feature, Apollo 11 site.” By comparison, the origin of Lovell Crater on the Moon’s farside reads “James A., Jr.; American astronaut (1928–Live).”

Thus, officially, the association of Marilyn Lovell with the mountainous feature is merely a back story, like that of Geneviève de Laistre with the lady’s face at Promontorium Heraclides. But the name will serve to remind future explorers of the important role, and sacrifice, of those “who also serve who only stand and wait” — the wives of the astronauts. They helped make history, and the triumph belongs as much to them as to their husbands who actually went to the Moon.