Stars form inside dense pockets of frigid gas and dust called molecular clouds. There, turbulence twists them into knots that eventually collapse under their own gravity. A central core called a protostar emerges, surrounded by a flattened disk of gas and dust. If enough mass is collected — a process that typically takes between 10,000 and 10 million years — the critical temperature of 10 million kelvins (18 million degrees Fahrenheit) is reached, triggering hydrogen-to-helium nuclear fusion.

A star is born. As the new star emits radiation, it’s absorbed and re-emitted by hydrogen in the surrounding gas cloud, creating the characteristic reddish glow of an emission nebula.

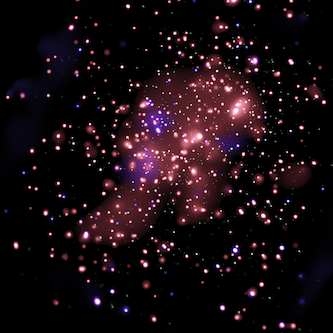

One such star-forming region is NGC 6357, located 3.3° northwest of Scorpius’ stinger stars, Shaula (Lambda [λ] Scorpii) and Upsilon (υ) Sco. Nicknamed the Lobster Nebula for its appearance in photographs, NGC 6357 is a large, irregular patch of ionized hydrogen containing many evolving protostars. These embryonic stars-to-be are shielded within dark disks of gas, akin to celestial wombs.

NGC 6357 has already spawned several hot, massive stars that are no more than 1 million years old. Fifteen of those form the sparse open cluster Pismis 24. The cluster’s brightest star, cataloged as Pismis 24–1, is actually a triple-star system, with each member ranking among the most luminous and most massive stars known.

Scorpius contains other open clusters that are easier to see. M6, the Butterfly Cluster, is a collection of 80 suns between 80 and 100 million years old, scattered in a pattern that resembles a butterfly in flight. Binoculars resolve about three dozen points in M6, while low-power telescopes display dozens more. Although most appear whitish or blue-white, the brightest is an orange stellar ember found east of the cluster’s center. Known as BM Scorpii, this spectral type K giant fluctuates slowly and erratically from 7th to 9th magnitude across an average of 850 days.

Nearby, M7, known as Ptolemy’s Cluster, is about twice as old as M6. More than 30 of its stars are brighter than 10th magnitude and burst into a beautiful array through binoculars. M7 looks even larger than M6, so use your lowest magnification for the best telescopic view. M6 and M7 are older than Pismis 24, but they are far younger than our Sun.

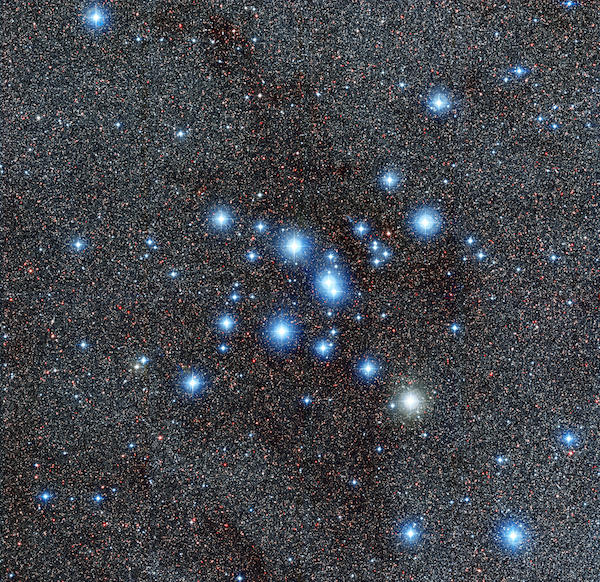

The region around Zeta (ζ) Scorpii includes stars of all colors scattered like gems. (Arranged in order from hottest to coolest, stars are classified as spectral types O, B, A, F, G, K, and M.) The striking open cluster NGC 6231, nicknamed the Northern Jewel Box, is an assortment of 120 hot type-O and type-B stellar sapphires. When viewed through binoculars or a rich-field telescope, it displays a brilliant blaze of suns bound within a 15′ circle. Based on spectral analysis, the cluster is only between 2 and 7 million years old.

Our Sun is a main-sequence star, as are several fainter stars of Scorpius, including HD 147513, a 5th-magnitude type-G star about 6° west of Mu (μ) Sco. Lying 42 light-years away, it’s 11 percent more massive than our Sun but only about 10 percent as old. At least one exoplanet orbits it. That planet, HD 147513b, is about 1.2 times the mass of Jupiter and follows an eccentric path that takes it closer to its star than Earth is from the Sun, and farther out than Mars.

If we are looking for a “solar twin,” then our best bet is 5th-magnitude 18 Scorpii, just inside the constellation’s northern border. Located 45.3 light-years from Earth, 18 Sco radiates 6 percent more energy than the Sun and is believed to be 2.9 billion years old. Some astrobiologists feel that this is one of the most promising nearby candidates for hosting life on an orbiting planet — that is, if such a planet exists. So far, none has been detected.

One of the finest globulars in the summer sky is M4, just a degree west of Antares. At first glance, M4 appears as a round blur. But a closer look will show that its core is bisected by a bright line of light. This odd appearance is visible in telescopes with apertures as small as 3 inches. Larger scopes reveal it is actually a chain of 11th-magnitude cluster stars that coincidentally line up in a row.

While touring Scorpius, don’t miss globular cluster M80, just northwest of Omicron (ο) Sco. It’s fainter than M4, but still visible through binoculars. Even 8-inch telescopes, however, have a difficult time resolving individual stars, since none shines brighter than 14th magnitude. Instead, most observers describe its texture as “mottled.”

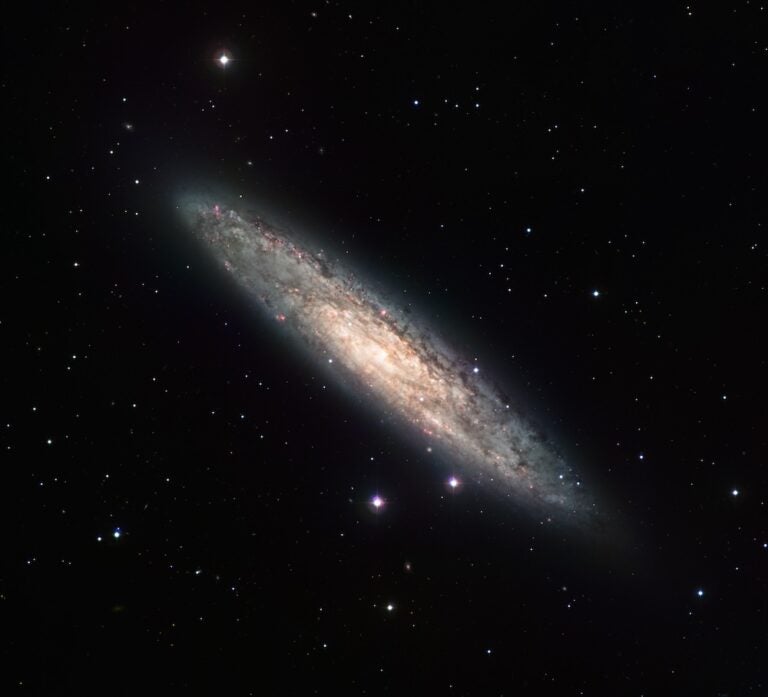

As the supply of fusible hydrogen in a star’s core dwindles, helium begins fusing. But it does so at a higher temperature than hydrogen, which causes the star’s outer layers to expand and to cool as they move farther from the core’s energy. The star finally leaves the main sequence and heads into its next evolutionary stage. Stars like our Sun ultimately will turn into red giants, while more massive stars will evolve into red supergiants.

One of the most famous red supergiants is Antares. If placed in the center of our solar system, its outer edge would extend beyond the orbit of Mars. Antares is about 12 times more massive than our Sun, but its surface is only about half as hot. Back when it was on the main sequence, it was much hotter and about 50 percent more massive than it is now. Current estimates give its age as only 12 million years.

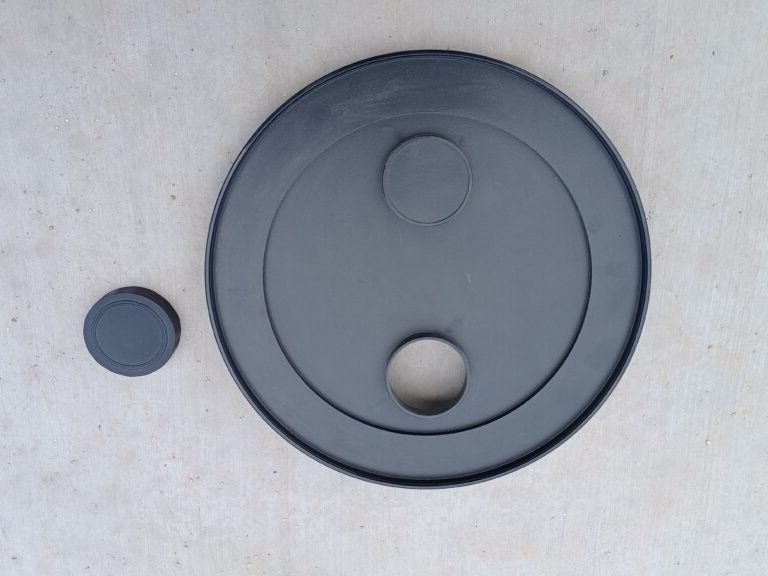

Our Sun and stars up to about three times more massive will ultimately end their days by throwing off their outer layers in an expanding cloud known as a planetary nebula. Of all the planetary nebulae in Scorpius, NGC 6302 is the easiest to spot. You’ll find it 4° west of Shaula. At first glance, it looks like a small, circular glow. But at magnifications over 100x, 8-inch and larger scopes expose the complex structure that gives rise to its nickname, the Bug Nebula. Two faint extensions, one to the east and the other to the west, look like “wings.” The central star, a white dwarf, remains hidden from view due to enveloping dust.

Another interesting planetary, NGC 6337, the Cheerio Nebula, is 2° southeast of NGC 6302 and 2.5° southwest of Upsilon. It is also best examined at moderate magnifications. A narrowband or Oxygen-III filter will also help. A filtered 10-inch scope will show a faint, perfectly round ring. An unrelated star overlaps the northeastern edge, but the central star remains invisible.

If you could slice a red supergiant in half, you would find layers, or shells, of increasingly heavier elements inward toward the core, like a stellar onion. Hydrogen would form the outermost shell, followed by helium, carbon, neon, oxygen, and so on all the way to iron. As evolution continues, nuclear fusion restarts in each shell as critical temperatures and pressures are met. That is, until iron is reached.

Neutron stars and black holes are detectable by their emission of X-rays. The first extrasolar X-ray discovered and strongest source in the sky, save for the Sun, is the neutron star Scorpius X-1, about 48′ south-southeast of 6th-magnitude HD 146850. We can’t see Scorpius X-1 directly, but it’s in a binary system, so we can at least try for its faint companion star, V818 Scorpii, which fluctuates between 12th and 13th magnitude.

Chinese astronomers recorded a supernova in Scorpius in a.d. 393. It shone as brightly as magnitude −1 and remained visible for eight months before fading from view. Today, we know the remnant as

SN 393 or G347.3–0.5. But when we gaze its way now, we see nothing. At least, not at visible wavelengths. Only its emission of X-rays and gamma rays gives it away.

While there is no visible supernova remnant in Scorpius, in one sense, everything we just examined is a supernova remnant. Just about every nature-made element on the periodic table beyond iron was likely created during a supernova. With the possible exception of merging neutron stars, no other natural process is known to possess the conditions needed to form these heavier elements. Therefore, much of the lead, gold, silver, copper, and nickel that we detect in the cosmos were created during the detonation of supernovae. You and I are, at least in part, supernova remnants. The late Carl Sagan said it best: We are all made of “star stuff.”