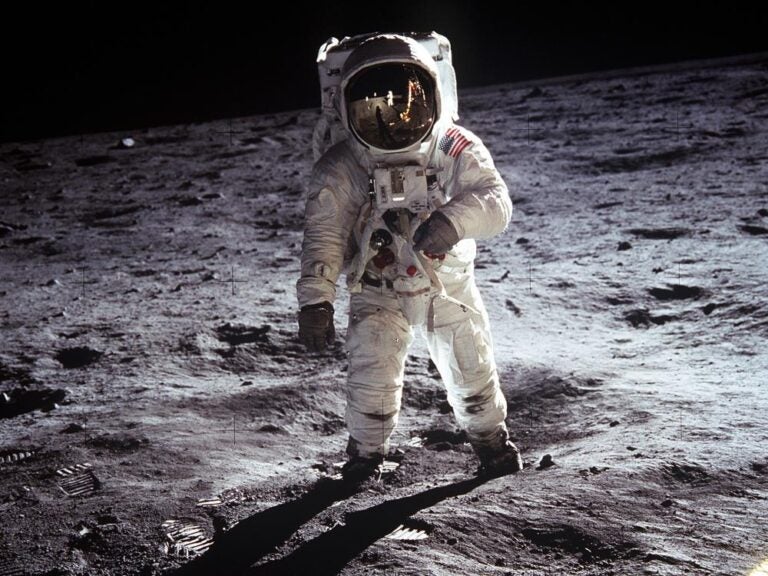

An astronaut, a little hop, and a witty quote: Neil Armstrong’s first lunar footsteps are ingrained in the minds of all humankind. But that first Moon landing might not have been such a historic cultural moment if it weren’t for NASA’s savvy public relations team.

Richard Jurek is a marketing executive and co-author of the book Marketing the Moon: The Selling of the Apollo Lunar Program. He says NASA’s move to real-time, open communication made Apollo 11 “the first positive viral event that captured the world’s attention.”

Before NASA was established in 1958, rockets were the military’s purview; that secretiveness carried over into the agency’s early days. At first, NASA followed a “fire in the tail” rule, publicizing a rocket’s launch only when it was already in the air, preventing it from being tampered with or prepared for. But as the agency evolved, it started announcing more details about the Apollo program. It championed its astronauts, talked openly about mission goals and challenges, and shared launch times so people could watch.

“If it had been run like it was under the military,” Jurek says, “we would not have had that sense of drama, that sense of involvement, that sense of wonder.”

Instead, all the PR and press hype in the years ahead of Apollo 11 brought the human spaceflight program directly into people’s living rooms.

Along for the ride

As the drama of the space race neared its climax, NASA’s PR officials pushed for live television broadcasts of the first humans to walk on the Moon.

Not everyone thought it was a good idea. The technology for airing live lunar missions, including cameras small enough for spaceflight, didn’t exist yet. Some engineers worried that developing that equipment would distract from efforts to achieve a lunar landing.

But NASA’s communications team argued that telling the story was just as important as the achievement itself. Live TV would bring the American people — and international viewers — straight to the Moon.

“I vividly recall watching the Apollo 11 landing and moonwalk at my parents’ home — it was incredibly inspiring,” says Alan Stern, principal investigator of the New Horizons mission to Pluto and beyond. “I think Apollo turned a huge number of my generation on to STEM careers and ultimately created the workforce that gave us things like the PC and internet revolutions.”

Come landing day, which conveniently fell on a Sunday night, more than half a billion people worldwide huddled around TVs and radios to tune in to the historic moment. “We were able to come together and do something that was exciting and interesting and brought the world together,” says David Meerman Scott, marketing strategist and co-author of Marketing the Moon. “I don’t know that we’ve done anything like that since.”

The exhilaration of the space race and the exploration of the Moon echoed through the arts — especially in science fiction.

Historian Margaret Weitekamp curates space memorabilia and science fiction objects at the National Air and Space Museum. A lifelong sci-fi fan, she studies how ever-changing attitudes toward spaceflight are represented by collectibles and works of science fiction.

“We talk a lot about popular culture reflecting society,” Weitekamp says. “It’s not some sort of magic mirror. It’s created by people who are very much a product of their time.”

For example, Jules Verne’s 1865 novel From the Earth to the Moon depicts Americans launching themselves to the Moon with a giant cannon, as cannons were a prominent technology in the American Civil War. A century later, during the civil rights movement, Star Trek showed an ethnically diverse crew on the starship Enterprise. This vision of different races harmoniously working together added to the optimistic tone of the show, Weitekamp says, giving viewers hope for the future of spaceflight.

A long trip for a small step

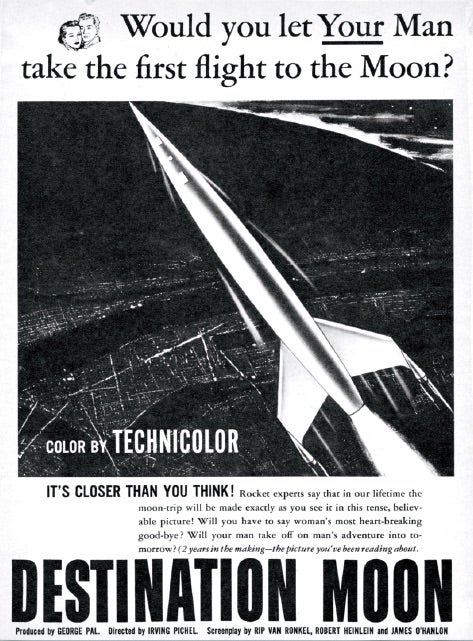

Space exploration has been featured in films since long before Apollo. In 1902, A Trip to the Moon — inspired in part by Verne’s aforementioned novel — proved that sci-fi could thrive in the new medium of movies.

Sci-fi’s vision of spaceflight evolved as the decades passed, of course. “The [portrayals] that are focused on the reality of what’s going on and realistic space programs tend to fall away in the 1960s, because they can’t really compete with the real thing,” Weitekamp says. “And so what you get are more extrapolated visions of what spaceflight could be,” as in Star Trek.

When the Apollo missions kicked off and people realized that going to the Moon wasn’t just a fantasy anymore, another prominent theme began to develop in sci-fi, says literature professor Brian Willems. Willems, of the University of Split in Croatia, studies how the Moon has appeared throughout the history of film. When it comes to the Moon landings, he says, it’s the journey, not the target, which really captured our imaginations.

For example, the film Countdown (1968) depicts the first Moon landing, but it primarily focuses on the challenge of getting to the surface instead of what happens next. In the movie, when Americans learn the Soviet Union will likely reach the Moon first, they abandon the Apollo program for a quicker backup plan: They send a lone astronaut on a one-way trip and plan to coordinate his return later. Like the real-life space race, the movie’s entire premise is beating the Soviets to the Moon.

“It was all about traveling to the Moon and the ability to do it, rather than about some experience on the Moon itself,” Willems says. He suggests such pre-Apollo 11 films reflect the real-life Apollo missions, in that their primary purpose was to highlight the American pride and sense of accomplishment that would come with besting the Soviet Union.

We’ve landed on the Moon. Now what?

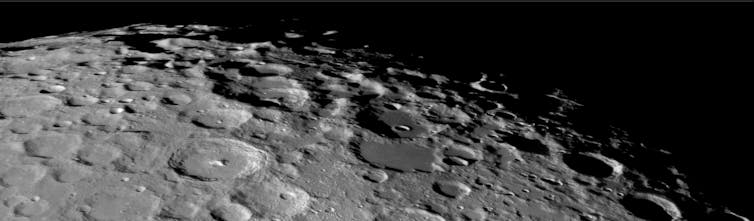

The journey to the Moon was a thrilling adventure, but the Moon itself wasn’t as exciting a subject, Willems explains. When Apollo 11 landed humans on the Moon in July 1969, it stunned the world, but it also revealed just how lifeless the lunar surface really is. So, to liven up an otherwise bland setting, wildly fantastical elements began appearing in sci-fi’s lunar stories.

The 1970s TV show Space: 1999 starts by blasting the Moon from Earth’s orbit with explosions, sending a populated Moon base hurtling through space. In the 2011 horror movie Apollo 18, viewers are shown fictitious “lost footage” of the canceled mission, which reveals deadly lunar aliens camouflaged as rocks. In 2012’s Iron Sky, it’s not aliens, but Nazis, who have been hiding on the Moon since World War II. Still other movies turned the plainness of the Moon into its own character: The root of the 2009 movie Moon is the sense of loneliness and isolation felt by a solitary person working at a dull, secluded lunar mining site.

As the fervor of the space race cooled, additional trips to the Moon lost a bit of their novelty. Landing on the Moon had made it a less exotic setting, prompting sci-fi to adapt by focusing the audience’s attention elsewhere.

While scouting landing sites for the Apollo missions in 1966, NASA’s Lunar Orbiter 1 took the first full-view photograph of Earth from the Moon; during Apollo 8 in 1968, astronaut William Anders became the first human to capture such a shot. Once we started to see the first photos of Earth taken from the Moon, Willems says, movies with lunar scenes also began to show Earth in the background. For example, in the 1968 classic 2001: A Space Odyssey, a scene prominently features our blue planet majestically floating above a Moon base.

“A lot of these films, they pretend to be about the Moon, but they’re really about the Earth,” Willems says. “It’s all about how the Earth sees the Moon and not about how the Moon is a different experience or a different place than Earth in some way.”

And this gets to the heart of how the Apollo missions influenced the visions of science fiction. Early on, creators of sci-fi saw the Moon as a bizarre and unexplored setting that could harbor surprising secrets. But as a trip to the lunar surface became more and more likely, sci-fi shifted its focus to the journey itself. And, once we finally reached the Moon, we were presented with humbling views of our home planet, ultimately forcing us to step back and reconsider humanity’s true place in the universe.

As Weitekamp says, “Spaceflight, I think, is a rich backdrop for telling different kinds of stories.”

Did Apollo boost the economy? Probably not how you think.

It’s a believable story. With the launch of the space race, the U.S. flings itself into a flurry of activity, training more scientists and engineers and creating jobs in technology and manufacturing, ultimately boosting the nation’s prosperity. But it isn’t quite clear yet how much the space race actually affected the U.S. economy.

“There’s really not that much evidence,” says economist Alexander Whalley of the University of Calgary. He and colleague Shawn Kantor, an economic historian at Florida State University, are working on a project to measure how the space race affected jobs and economic prosperity in U.S. cities. “There’s a lot of stories kind of running around, and we’re trying to actually calculate or estimate how big are those effects,” he says.

Economic productivity in the U.S. was booming in the 1960s, according to Whalley, but growth slowed in the 1970s. This calls into question just how much of a boon the space race really was.

It’s a question that hasn’t gotten much attention from economists yet — at least not in a rigorous, quantitative way. Kantor suggests the space race wasn’t quite old enough for economic historians like himself to study until recently. “It’s just now becoming economic history,” he says.

Whalley and Kantor caution that these results are preliminary; they’re working on investigating more deeply as the project continues. But so far, their findings suggest that the space race wasn’t all good news for the job market. While companies contracted by NASA grew and hired more workers, employment in other companies seemed to drop; the researchers hypothesize that improved computing technology from space race efforts might have resulted in fewer necessary workers in other industries.

Whalley and Kantor aren’t trying to say whether or not the space race was worth it. But by measuring the effects it did have, they hope to help governments make informed decisions about when and how to invest in science and technology — and whether it’s appropriate to use economic growth as a motivation for doing so.

Training scientists, or citizens?

When the Soviet Union launched the Sputnik satellite in 1957, then-President Dwight D. Eisenhower pushed for strengthening science education in the U.S., saying the nation needed more scientists. But it’s not quite accurate to say Sputnik’s launch led the U.S. to change its science curriculum, according to John Rudolph of the University of Wisconsin–Madison, an expert on the history of science education in the U.S. “When Sputnik came along, that’s what got the public’s attention,” Rudolph says, “but the science [education] reforms were already well underway in response to what [the United States] thought was going on in the Soviet Union.”

Regardless of what triggered the reforms, science education saw dramatic changes during this time. Before the mid-1950s, high school science education in the U.S. was focused on everyday applications like nutrition and what Rudolph calls “refrigerator physics” — the science you need to understand how appliances work. But scientists were calling for the American public to learn about what they actually do, like experimentation and data analysis.

The purpose of these educational reforms after the mid-1950s was to help the general public understand the research funded by their taxes and to garner support for scientific research as a whole, not necessarily to create more scientists and engineers, says Rudolph.

“If we just start focusing on trying to get people to do science,” Rudolph says, “we lose trying to understand what science is as a larger enterprise and as an institution in society.”

Scientific research doesn’t always have clear applications or result in economic gain right away. Societies must decide whether investing in science should always be a means to an end or whether it is a worthwhile goal in its own right.

“Should we, as a society, be having another space race . . . as a way to create jobs in the future?” Whalley asks. “Or is the space race more about getting people to the Moon?”

Have you ever noticed a diner, or perhaps a motel, gas station, or drive-in, that looks like it would fit in the Jetsons’ neighborhood? A confluence of car culture and the Atomic and Space Ages, Googie architecture (pronounced GOO-gee) is probably the reason behind that quirky, retro-futuristic look.

After World War II, U.S. suburbs were growing fast, leading to many more drivers on the roads. To capitalize on these commuters, businesses needed attention-grabbing buildings and signs that captivated those riding by.

“The architecture itself had to be really bold and vivid and noticeable,” says Alan Hess, an architect and historian who has written extensively on modern architecture in the mid-21st century. “At that time, one of the things that would really attract attention was anything that looked really, really futuristic, really modern, really up to date.”

The future looked bright in the 1950s and 1960s. The birth of atomic science brought promises of advanced societies powered by nuclear energy, while the beginnings of the space race made people realize that humans might soon venture to the Moon or Mars. And because a futuristic era seemed just beyond the horizon, the shift to an ultramodern architectural style was almost inevitable.

Television also reflected this optimism toward technology — it would make our daily lives easier, and allow for ever-more-ambitious achievements. In the early 1960s, The Jetsons portrayed a high-tech society with flying cars, housekeeping robots, and meals prepared with the push of a button. A few years later, Star Trek painted an idealistic future where humankind uses advanced technology to explore and understand the universe . . . as well as enjoy meals prepared with the push of a button.

Googie architecture exemplified this sanguine outlook. The style used unconventional shapes, eye-catching colors, and modern materials — including glass, chrome, and lots of plastic. It was bold, playful, and exuberant.

Because many businesses, such as restaurants, car washes, and bowling alleys, were being built in this style, Googie architecture was easily accessible to the average American. You didn’t need to hire an architect to design a modern, futuristic house for you. You could get a taste of Googie by just hopping in your car and scoping out your local diner.

“All you needed was, you know, the price of a hamburger. And you could go into any of these restaurants, and the designs of them were intended to make you feel as if you were participating in this new age,” Hess says.

By the early 1970s, however, the Googie style waned in popularity. After Apollo 11’s lunar landing in 1969, space travel was becoming less of a novelty. And with the rise of the ecology movement, Hess says, enthusiasm for futuristic technology like nuclear power was petering out. The curved roofs and shiny surfaces of Googie were no longer seen as chic, so businesses turned back to traditional styles that were perceived as more Earth-friendly.

Still, Googie remained popular for a good two decades or so —fairly long for a trendy architectural style. And although many Googie buildings were torn down after the space race, conservationists and architectural historians around the country now are working to preserve any that remain as historic landmarks. Some, like the nation’s oldest existing McDonald’s in Downey, California, have even qualified for the National Register of Historic Places.

Hess says visiting these sites can really give you a feel for their era. “You get that sense of optimism,” Hess says. “You can still go to these places and feel that. It’s very tangible when you’re sitting there, having a root beer float.”

Celebrating Apollo with postage stamps

You know you don’t need another refrigerator magnet or souvenir shot glass — so why are gift shops so enticing? Owning memorabilia is a way for us to feel connected to things larger than ourselves, whether it’s our favorite baseball teams, vacation destinations, or concerts.

“When you look at memorabilia, you get a sense of the kinds of things that people wanted to have a souvenir of, in the kind of original French sense of the word, as a way to go back or a way to remember,” says Weitekamp, the curator of space memorabilia at the National Air and Space Museum.

The Apollo missions were no exception. The Apollo program — and especially the first Moon landing — captured imaginations and spawned memorabilia across the globe.

Consider postage stamps: The U.S. alone has issued at least six stamps honoring Apollo 11, and countries worldwide have issued countless others. “Nations around the world wanted to be able to show that they celebrated this human achievement,” Weitekamp says.

Of course, not all nations were equally eager to plaster their stamps with U.S. astronauts or NASA spacecraft. After all, the space race was one battlefront of the Cold War, and the Soviet Union was busy printing its own postage stamps with the faces of its cosmonauts. And some nations’ stamps depicting the Apollo missions de-emphasized U.S.-specific imagery, like flags, to portray the Moon landings as a general human achievement rather than a specifically American one. “In the issuing of those stamps, there’s some reflection of that broader political context,” Weitekamp says.

These stamps, curated from the author’s personal collection, represent just a few examples of the diverse stamps that were created to commemorate Apollo.