The flight of Apollo 11, the mission chosen to attempt the first lunar landing, was scheduled to launch July 16, 1969. After the success of Apollo 10, it appeared that NASA would indeed keep the promise that John F. Kennedy made eight years earlier.

The crew consisted of an all-veteran, multipurpose group: Commander Neil Armstrong, Command Module Pilot Michael Collins, and Lunar Module (LM) Pilot Buzz Aldrin. For all three, it would be their second time in space.

Armstrong, 38, an Ohio-born naval aviator and test pilot, was among the second group of NASA astronauts. Along with David Scott, he flew aboard Gemini VIII in 1966. Collins, also 38, was born in Rome. The son of a U.S. Army major general, he became an Air Force test pilot before being selected to the third group of NASA astronauts. He, with John Young, was a veteran of Gemini X, which flew in 1966. Aldrin, 39, was an engineer and Air Force pilot who was selected in the third astronaut group; he flew with Jim Lovell on Gemini XII in 1966. The support crew for Apollo 11 included capsule communicators (capcoms) Charlie Duke, Ronald Evans, Ken Mattingly, Bruce McCandless, Harrison Schmitt, and Jack Swigert.

Mission planning went smoothly. Not everyone in NASA was amused by the informal names of the Apollo 10 command and lunar modules — Charlie Brown and Snoopy, respectively — so more serious names were given to the Apollo 11 counterparts: Columbia for the command module and Eagle for the LM. Eagle took its name from the emblem of the United States. Columbia borrowed its name in part from the European historical name for the Americas, and also in a reference to Jules Verne’s 1865 novel, From the Earth to the Moon.

Anticipation for the launch was immense. After years of planning, the Gemini missions, and all of the Apollo mission testing, the big day was finally near.

The Beatles played their last public concert, on the London rooftop of Apple Records. Led Zeppelin released its first album. Plans came together for Woodstock, to be held in August in New York. Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones drowned in his swimming pool. Blind Faith played its first show in front of a massive crowd in London’s Hyde Park.

And the world’s eyes increasingly turned toward that bright ball of light in the night sky.

We have liftoff

Wednesday, July 16, 1969, dawned clear and bright at Kennedy Space Center in Florida. Thousands of people crowded along roads, around the public viewing areas, and even far off in other parts of the state to watch the rocket’s towering flame head skyward. Jack King, NASA’s chief of public information, supplied commentary for TV network coverage.

The launch was picture-perfect, and within 12 minutes the craft entered Earth orbit at an altitude of about 100 nautical miles (185 kilometers). After an orbit and a half, the third-stage engine fired and moved the spacecraft into a trans-lunar injection, sending it toward our celestial neighbor. Some 30 minutes later, the crew performed the maneuver that separated the command/service module from the spent rocket stage and allowed docking with the LM. After the rocket stage was discarded, the command module and the LM headed moonward.

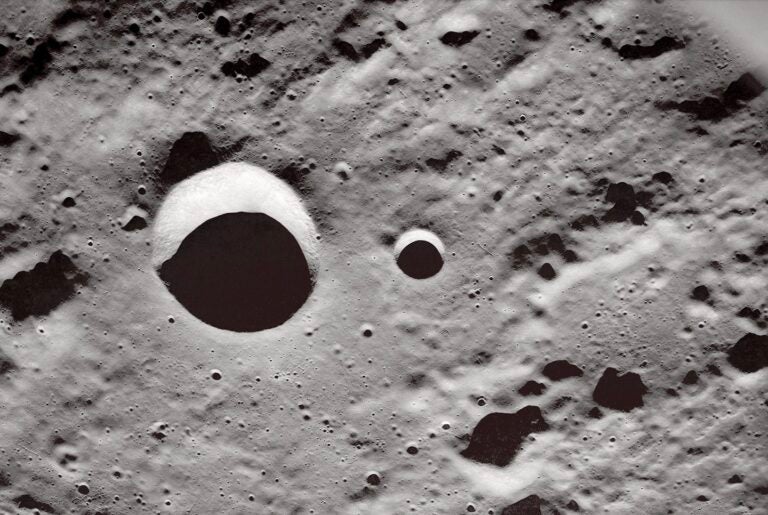

The cruise to the Moon lasted three days, and by July 19, the craft passed close enough to the Moon to fire its propulsion engine, setting it on a course to orbit the Moon. Armstrong, Aldrin, and Collins orbited the Moon 30 times and observed all manner of craters and other formations, paying particular attention to the region where they planned to land, the Sea of Tranquillity. Previous unmanned spacecraft had imaged the area, and it appeared to be a safe landing site because of its flat terrain. The exact position was about 12 miles (19 km) southwest of the crater Sabine D, a 1.5-mile-diameter (2.4 km), dish-shaped welt on the lunar surface that later would be renamed Collins in honor of the command module pilot.

Stick the landing

On July 20, operations commenced that would lead to humanity’s first steps on another world. Collins stayed aboard Columbia as Armstrong and Aldrin climbed aboard Eagle and began a descent operation. As the two craft separated, Collins carefully viewed Eagle for any possible signs of physical damage as the lunar lander turned in front of him.

Standing inside the cramped LM, Armstrong and Aldrin frantically checked readings and looked through the craft’s narrow window. As they recognized landmarks, they realized they were seeing them about four seconds ahead of the planned exercise — they were going “long,” and the spacecraft would pass the intended landing site.

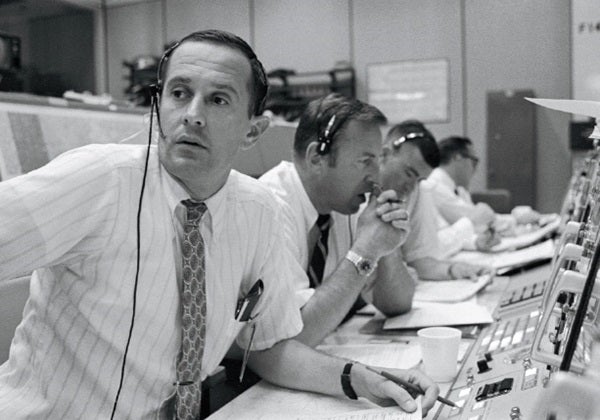

As they slowly descended and approached an altitude of about 6,000 feet, two program alarms sounded: The spacecraft computer recognized that it could not accomplish all the checks it should in real time. At Mission Control in Houston, engineers were not overly concerned, and they allowed the descent to continue. Later, NASA computer programming chief Margaret Hamilton wrote that the overload occurred due to a checklist error for the spacecraft preparation, and that the computer automatically ignored lower-priority tasks in order to focus on the descent.

As the LM slowly lowered at the speed of a hotel elevator, Armstrong peered outside and saw a boulder-strewn field, north of a crater later determined to be West Crater. He took semi-automatic control of Eagle and realized the craft had very little fuel left. In fact, the astronauts received an erroneous “low fuel” warning because of fluid sloshing in the tank and washing away from a sensor. But fuel was still running out. Mission Control was aware of the fact, too. As Eagle lowered — no one knew exactly what the landing impact would feel like — it had less than half a minute of fuel remaining.

The spacecraft sank toward the Sea of Tranquillity. Moments before landing, Aldrin called out, “Contact light!” as one of the hanging probes dangled onto the powdery lunar surface. Three seconds later, the craft landed squarely, and Armstrong said, “Shutdown.” After a few more words from Aldrin and Armstrong, Duke blurted: “We copy you down, Eagle.”

Moments later, Armstrong uttered, “Houston, Tranquillity Base here, the Eagle has landed.” Duke replied, with a bit of stumble, “Roger, Twan — Tranquillity, we copy you on the ground. You got a bunch of guys about to turn blue. We’re breathing again. Thanks a lot.”

It was July 20, 1969, at 4:18 p.m. EDT, and Duke wasn’t the only one who was relieved: Millions around the world were watching, and celebrations erupted when the news of the successful landing broke. Kennedy’s vision had come true. Humans had landed on another world. And now the fun part was coming — the exploration. What would the Moon really be like?

About two and a half hours later, Armstrong and Aldrin prepared to walk on the Moon, as Collins orbited overhead in Columbia. They were supposed to sleep for about five hours, but they were too excited. Before readying for the moonwalk, Aldrin broadcast a message home: “This is the LM pilot. I’d like to take this opportunity to ask every person listening in, whoever and wherever they may be, to pause for a moment and contemplate the events of the past few hours and to give thanks in his or her own way.” Then Aldrin, an elder at his Presbyterian church, held a communion ceremony for himself

.

First steps

About two and a half hours later, Armstrong and Aldrin prepared to walk on the Moon, as Collins orbited overhead in Columbia. They were supposed to sleep for about five hours, but they were too excited. Before readying for the moonwalk, Aldrin broadcast a message home: “This is the LM pilot. I’d like to take this opportunity to ask every person listening in, whoever and wherever they may be, to pause for a moment and contemplate the events of the past few hours and give thanks in his or her own way.” Then Aldrin, an elder at his Presbyterian church, held a communion ceremony for himself.

Peering out from Eagle’s windows, Armstrong and Aldrin could see about a 60°-wide field of the surface, which appeared bright and gray. The pair intended to plant a U.S. flag in the soil and deploy an experiment called the Early Apollo Scientific Experiment Package (EASEP), which would collect various data. After more than two hours of preparation, at 10:39 p.m. EDT on July 20, Armstrong opened the LM’s hatch and began to squeeze through it. At 10:51 p.m. EDT, Armstrong began climbing down the nine-rung ladder to the surface; a mounted slow-scan TV camera captured his descent. At 10:56 p.m. EDT, Armstrong stepped onto the lunar surface. Black-and-white TV footage of the event was broadcast to countless millions of homes around the world. As kids at the time, many of our readers surely remember the thrill of staying up late to watch this incredible moment.

Mounted on the LM was an aluminum plaque with icons showing Earth’s hemispheres, the astronauts’ signatures, and a statement from Nixon: “Here men from the planet Earth first set foot upon the Moon, July 1969 A.D. We came in peace for all mankind.”

Armstrong then collected a soil sample. Some 12 minutes later, Aldrin climbed down the ladder and joined his colleague on the surface. The astronauts planted the U.S. flag, described walking around in the light lunar gravity as “easy,” and spoke to Nixon via a telephone-radio hookup from the White House.

The moonwalkers kicked up substantial amounts of dust as they walked around. As they then focused on experiments, they shot photographs, deployed a seismometer, set up a retroreflector, and collected rock samples. The excursion was to last 34 minutes, but the tasks took longer than expected. So Houston gave them 15 more minutes. Armstrong strolled almost 200 feet from the LM.

After only 21 hours since landing on the Moon, it was time to go home. Aldrin entered the LM first, followed by his comrade. The two had collected more than 47 pounds (21 kilograms) of rocks. Aldrin accidentally damaged a circuit breaker inside the LM, leading to concern about the engine. But after seven hours of rest, the pair woke up, fired the ascent engine, and lifted off. They reconnected with Collins on Columbia and set a course back to Earth. The crew splashed down in the Pacific Ocean on July 24, returning as worldwide heroes.

The Moon had been conquered. Kennedy’s dream came true. A new era in human history began. And no one was exactly sure where this amazing moment would lead the world next.

Explore from home

The print version of this story contains several stereoscopic images for home viewing we are unable to include digitally. However, you can find these images in the July copy of our magazine, as well as in Mission Moon 3-D: A New Perspective on the Space Race by David J. Eicher and Brian May (with foreword by Charlie Duke and afterword by Jim Lovell), which presents the story of the historic lunar landings and the events that led up to them, told in text and three-dimensional images.

Mission Moon 3-D contains new and unique stereoscopic images of the Apollo Moon landings to show what it was like to walk on the lunar surface. The triumph of the Apollo 11 Moon landing takes center stage, with detailed stories and visually stunning images from the six lunar missions that followed. The book includes 150 stereo photos of the Apollo missions and space race — the largest group ever published — and presents photos never before seen in stereo.

The book delivers a comprehensive tale of the space race. New stories appear from the astronauts, including Jim Lovell’s anecdotes about the perilous return of Apollo 13.

Mission Moon 3-D also includes a history of the special and musical movements of the 1960s and beyond that transformed the world, from Vietnam and Woodstock to Live Aid. Don’t miss out on this unique treasure.

Mission Moon 3-D available at www.myscienceshop.com