NASA wasn’t always on board with astronauts taking the time to complete science experiments during the Apollo missions. “Fairly early in this business was when NASA told Gene [Shoemaker] that all [the astronauts] could do was plant the flag [during the first Moon landing],” USGS scientist Joe O’Connor said in a 2001 interview. “It was our job to convince NASA otherwise.”

Around this same time, the USGS team figured out a way to communicate, in real time, with the astronauts on the Moon. But when they pitched their idea for a Command Data Reception and Analysis facility to NASA, their aeronautical colleagues didn’t take kindly to the idea that a bunch of geologists would be “commanding” anything. In the end, the scientists were able to explain that their goal was to be available to assist the astronauts during their lunar expeditions, and NASA agreed. The Flagstaff communications room was renamed the Apollo Data Facility.

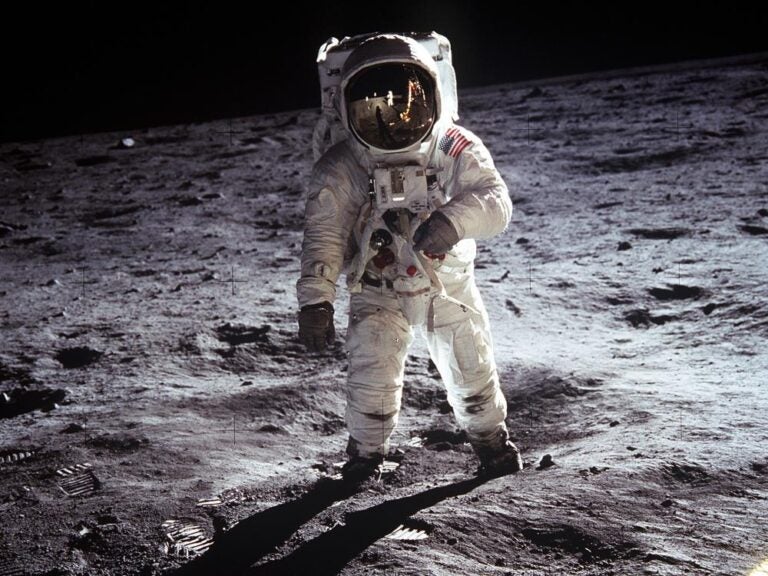

During the Apollo 11 Moon landing, Shoemaker and others from Flagstaff were in the Science Support Room at Mission Control in Houston. In the weeks after the first moonwalk, their studies of rock samples collected by Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin resulted in what would be the first of many breakthroughs in astrogeology — the geology of planetary bodies beyond Earth.