On the other hand, the word ephemera means something fleeting, changeable, temporary. This word refers to paper items that don’t last long or were meant for short-term use but have since become collectibles. Those 1977 ticket stubs from the original Star Wars movie are ephemera.

A great deal of astronomical ephemera exists. The material ranges from almanacs to early 20th-century astronomy-themed sheet music, from antique stereo cards to playing cards depicting famous astronomers. Then there are the tea and cigarette cards, produced for nearly 100 years, that covered how to find constellations, the development of the telescope, spectroscopy, space exploration, and more. A wide range of other items has survived the ravages of time as well.

The postcard era

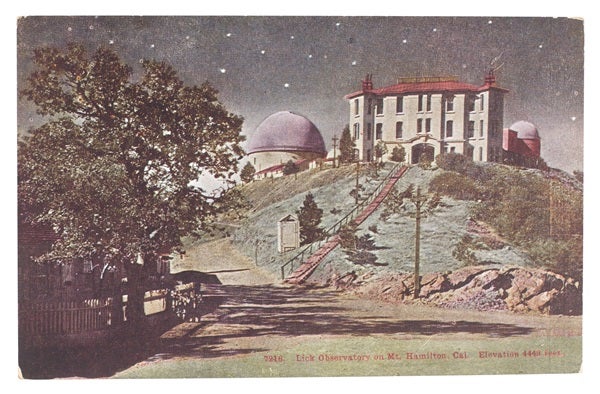

Postcards appeared with the rise of cheap and regular mail delivery. They first became popular in the mid-19th century in Europe, and then America. The cards usually showed a sentimental picture and a verse on the front, with room for the address and a message on the back. They also became “wish you were here” greetings with drawings and then photographs of interesting locations. Observatories were a favorite photographic subject.

Near the beginning of the 20th century, Lick Observatory in California appeared on many postcards. Some showed drawings of the observatory at night. A few even had holes poked out for the stars. When held up to the light, the “stars” seemed to twinkle in the sky above this marvel of 19th-century technology.

Yerkes Observatory in Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, was also popular. Postcards that span a century show many exterior and a few interior views. One card in my collection has a colorized image of the 40-inch Yerkes refractor. The message on the back is what makes it so special: “Dear Gary, this telescope gives me the idea to replace the mirrors in the baggage room.” It’s an odd response after seeing one of the most powerful telescopes in the world. Postcards of observatories from across the globe provide insights into a world that, in many cases, has been lost.

The 1910 appearance of Halley’s Comet also provided a wealth of material for postcard makers. The range of subjects ran the gamut from the artful to the comic. Originals of these cards are extremely rare. With the return of the comet in 1985, many of the 1910 cards were reproduced, along with new cards that may now be tucked away waiting for 2061, when Halley’s Comet returns.

Trade cards

Long before mailboxes were cluttered with endless color flyers and ads, merchants produced trade cards to promote their products. These were given out in stores and other points of sale. Throughout the 19th century, people collected these cards. One of the earliest cards in my collection is an ad for lessons in practical navigation. Captain E.A. Dunkerton advertised help for those who were studying to become master’s mates and pilots. This card may have been handed out in stores that sold nautical equipment.

As color printing became cheaper, cards became more elaborate and beautiful. The aim was to get consumers to keep the card because that reminded them of the product. The German company Liebig issued a series of trade cards showing different ancient goddesses, including Urania, the muse of astronomy. It is a beautiful card even though the back promotes Liebig’s Meat Extract!

Another set of such cards in Italian tells the life story of Galileo in great detail. The company that produced it also did a series about the planets and comets. Some cards used astronomical images simply to catch the eye. A trade card for optical equipment shows a number of elves deep in a cave, using a prism to create a lovely spectrum.

Decorative pieces

Antique prints, drawings, and even cartoons provide areas of ephemeral interest. It was common in the 19th century for print shops to produce decorative images for the home and collectors.

Two artists of note, Wilhelm Kranz and Etienne Leopold Trouvelot, produced beautiful astronomical artwork, which was reproduced many times. Kranz painted beautifully atmospheric images such as the Big Dipper and Little Dipper above a frozen field. Originals from these artists are quite valuable, but prints have also survived and are worth collecting.

Some images poke fun at astronomy and astronomers, and the public’s interest in both. The British satirical magazine Punch was particularly creative. One drawing shows a group of middle-class viewers bemused by a sidewalk astronomer.

The world of gaming also got into the act. Famous 19th-century astronomers such as Sir Robert Ball, Sir William Huggins, and Lord James Lindsay appeared on playing cards made by Vanity Fair.

Stereo cards

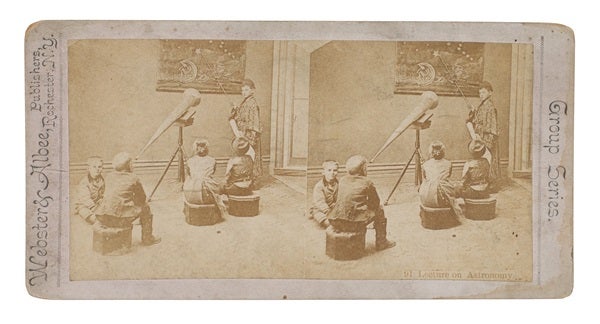

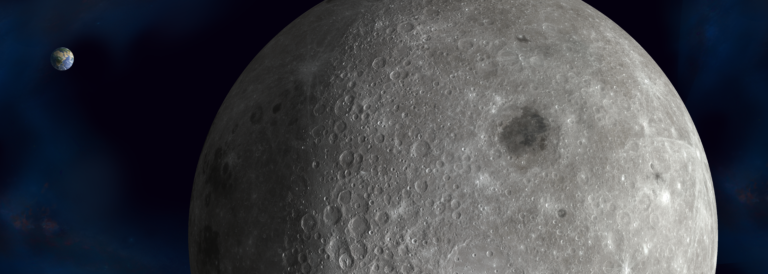

The first photograph of the Moon — taken in 1840 by astronomer John W. Draper — was printed on metal as a daguerreotype. Within a few years, paper photographs became common. Then two images were combined to create stereo cards.

By the 1860s, every middle-class home had a stereo viewer and a box filled with cards showing scenes from around the world. Some of the stereo cards boasted astronomical subjects. A stereo card of the Moon from this period was based on photographs by Draper. Unfortunately, many early cards were produced on poor-quality paper and have not survived in large numbers.

One of my cards shows a group of children involved in an astronomy lesson, with the young “professor” draped in his father’s dressing robe. Another has a fake image of Saturn with what appears to be cardboard rings. By the 1870s and beyond, both the paper quality and the artwork on the cards had become much better.

A card from 1902 shows the business end of the great equatorial refracting telescope at Lick Observatory, on Mount Hamilton in California. It almost makes the viewer want to reach in and turn the knobs. By the turn of the 20th century, these cards sported real celestial images of Saturn, Mars, nebulae, comets, and even meteors. This is how the public saw astronomy more than a hundred years ago.

Lucky Strike means …

By far, the most beautiful and prolific source of astronomical ephemera comes in the form of tea and cigarette cards. In 1875, the Allen & Ginter tobacco company began placing small, colorful cards into cigarette packages. Some of the earliest baseball cards were, in fact, produced as cigarette cards. The cards were issued in series to encourage smokers to buy more packs.

By the 1880s, the British cigarette company H.O. Willis also started to issue cards to increase sales. Other British manufacturers soon embraced this marketing idea enthusiastically, and, indeed, many of the best cards were printed in England. It wasn’t long before they were appearing in tea packages, chocolate tins, and other products. These cards covered every conceivable topic, including astronomy.

I was introduced to astronomical cigarette cards by the English astronomer of lunar nomenclature fame, Ewen Whitaker. These incredibly delightful and colorful cards are quite small, measuring only 2.5 by 1.5 inches (64 by 38 millimeters).

The cards always have a graphic image on the front and detailed information on the back. The series usually contained between 20 and 50 cards. That’s a lot of cigarettes! A collector could learn all the constellations, how telescopes and spectroscopes work, famous astronomers, and more. A real education could be gotten from these miniature cards.

At the beginning of the 20th century, John Player & Sons produced a set of 25 cards called “Those Pearls of Heaven,” showing the brightest constellations. They include Orion, Leo, Taurus, and even small finder star charts. The back of the card “Bears — Great and Little” explains: “Part of the Great Bear is the familiar Plough, also called Charles’s Wain. Between the Pointers is the Owl Nebula invisible to the unaided eye.” (Before you write in, I realize that last statement is a mistake. M97 isn’t between the Pointers.)

These cards reflect the astronomical knowledge of their time. A card by Wills Cigarettes shows a face-on spiral nebula — in other words, a galaxy. The back states it consists of “highly diffused gaseous matter, thought to have been expelled from the Milky Way.”

Mars is shown with a spider’s web of canals, while its surface is crisscrossed by waterways under a blue martian sky. The same set also illustrates volcanoes forming lunar craters. An illustration of an eclipse viewed from the Moon indicates a lunar surface that is sharp and craggy.

Many cards became small works of art in their own right. One card shows Halley’s Comet shining in a star-filled sky above a calm lake. Others feature polar explorers trudging over ice fields under the glow of the aurora australis and a fireball blazing across a darkened sky. Equipment like the Yerkes’ refractor or a brass spectroscope also appear on these cards.

Even the Zeiss projector at the London Planetarium appears on a Tonibell lemon juice card. Astronomers Sir Robert Ball, Hans Lipperhey, and Sir Isaac Newton also have places in these miniature encyclopedias of information. Of all the astronomical ephemera that might tempt a collector, these cards are the hardest to resist.

Astronomical almanacs

In 2009, Sotheby’s auction house sold a 1733 copy of Poor Richard’s Almanack by Benjamin Franklin for $556,500! This little publication of a few dozen pages was found tucked away on a shelf and forgotten for more than 270 years.

Almanacs have been around for centuries. Old European almanacs listing saints’ days and religious observances are rare and valuable. In early America, almanacs took on a different form. The agrarian society of that time needed particular information for successful farming, so Franklin and others began to fill this void with small annual publications. The Old Farmer’s Almanac (originally just The Farmer’s Almanac), which has been continually published since 1792, can still be found in grocery stores across America.

Almanacs contain a great deal of astronomical information. There was usually a page per month listing Moon phases, rise and set times of the Sun and the Moon, tides, the equation of time, and much more. Facing pages held information about planting times, seasonal changes, and general “useful” information.

Monthly weather predictions were also an important part of these publications. Unlike almanacs for professional astronomers, these slim volumes were meant to be used and then discarded. Many of them found their way to the outhouse. As a result, old almanacs are hard to find.

I have a copy of Leavitt’s Genuine, Improved New-England Farmer’s Almanack, and Scholar’s Astronomical Diary for the year 1822 in my collection. Like most almanacs, it was printed on poor-quality paper to keep down the price. This is another reason for the scarcity of such publications.

On the cover are illustrations of eclipses of the Sun and Moon for that year. Inside is more information about astronomical events, “Chronological Cycles,” and important dates. It even contains a small selection of “Pleasant [in other words, scientific] Experiments.” This is all followed by a page-per-month listing of important daily information.

It is the human connection that makes these almanacs so special. Many farmers made notes throughout them. For example, the original owner of my Leavitt Almanac recorded the first snowfall on October 28, as well as other information. This is the best type of ephemera because it reaches through time to touch us here in the future.

Brief glimpses

All these items provide a wonderful look into the history and understanding of astronomy from the 19th to the mid-20th century. Astronomical ephemera also give a fascinating look at how the public viewed this fast-developing science, and what information was important and useful to them. Many of these items are not only beautiful, but also provide incredible insight into the human response to the heavens. Whether through benign neglect, happy accident, or purposeful preservation, ephemera are a treasure for us all.