On the evening of September 11, 2017, Griffith Observatory hosted an enthusiastic group of observers. The assembled crowd looked through the 12-inch Zeiss refracting telescope, the centerpiece of the venerable public astronomy venue in Los Angeles. They watched as light from Saturn and its largest moon, Titan, passed through the telescope’s optics, where lenses bent and focused it onto their eyes.

The onlookers could see the beautiful rings circling Saturn, the planet’s yellowish cloud bands, and the orange-tinged dot of the big moon near the planet; what they couldn’t make out was a much smaller, human-made target. On that late summer evening, the Cassini spacecraft was just 75,000 miles (120,000 kilometers) from Titan on its final path toward Saturn. The spacecraft and Titan had enjoyed their “goodbye kiss,” as the astronomers and engineers on the mission called the last gravitational yank that would send the spacecraft into the planet it had been studying for 13 years.

These observers at Griffith were no ordinary members of the public. They were members of Cassini’s Project Science Group, watching their beloved spacecraft on its final journey around the giant world. “It was a magical evening,” says Cassini’s Project Scientist Linda Spilker.

Over the next few days, hundreds of scientists and engineers on the Cassini mission team would reminisce about the spacecraft, which had launched from Cape Canaveral, Florida, nearly 20 years earlier. But their thoughts were not all on the past: Cassini was still collecting data and sending it back to Earth.

On September 15, at 3:31 a.m. PDT, Cassini entered Saturn’s upper atmosphere at a shallow angle. It would travel through the gas for nearly 11/2 hours. The team members were gathered at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, where they watched and waited. “The room got quieter and quieter as we got down to those final minutes,” says Spilker. At 4:55 a.m. PDT, they saw the last signal from Cassini fade away on the screen. The room erupted in applause — not for the end of the mission, but for what the spacecraft and those hundreds of people had achieved.

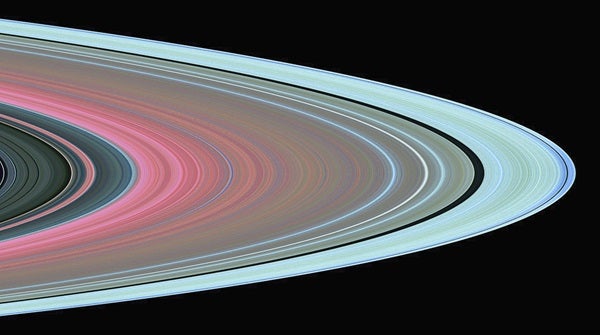

Cassini could probe Saturn’s ring structure by sending radio signals through the rings. In this simulated view of the A ring and the Cassini Division (at left center), red denotes particles 2 inches (5 cm) or more in diameter; green indicates particles less than 2 inches across; and blue signifies particles less than 0.4 inch (1 cm) across.

An extended stay

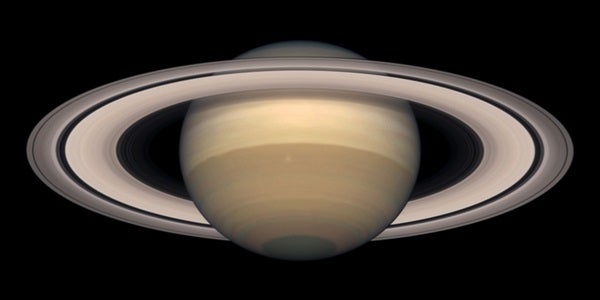

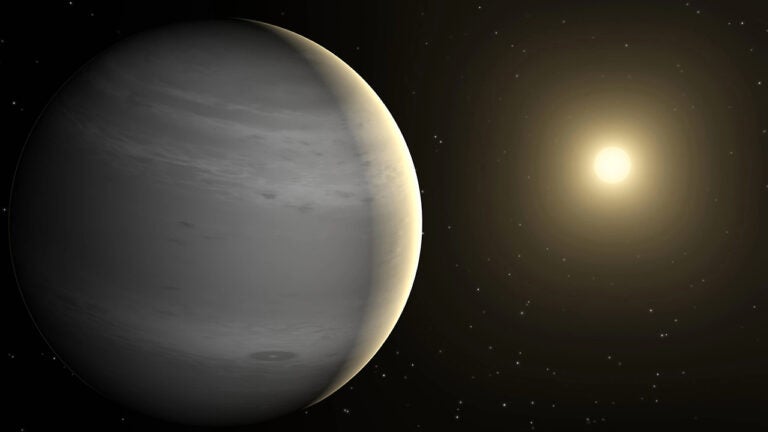

Spacecraft already had visited Saturn three times before Cassini arrived in mid-2004, so scientists had some inkling of what they might find. But as with any new mission — especially one involving a machine with 12 sophisticated instruments that would remain in orbit instead of flying past as its predecessors had — Cassini revealed a complex planet full of surprises. And that’s a good thing. “If Saturn had been exactly as expected, it would have been a lot more boring,” says Spilker.

Cassini arrived at Saturn for a primary mission set to last four years. But when mid-2008 came, the spacecraft continued with its Equinox Mission extension. And in September 2010, the mission began its Solstice extension, which ultimately bled into the Grand Finale. This final stage commenced in April 2017 and featured 22 close-in orbits that skimmed just above Saturn’s cloud tops.

Because Cassini’s 12 instruments were attached directly to the spacecraft, the entire contraption had to rotate for an instrument to point toward a specific target. That meant multiple instruments couldn’t observe the same spot at the same time. Instead, while one looked at a moon, another might observe Saturn’s rings. And that made the last five months of the mission — the Grand Finale — a work of impressive coordination. Although 22 orbits might sound like a lot, they aren’t much to work with when you have to divide the limited time during those close flybys among the full instrument lineup.

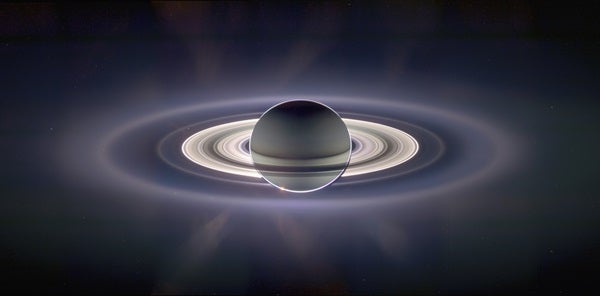

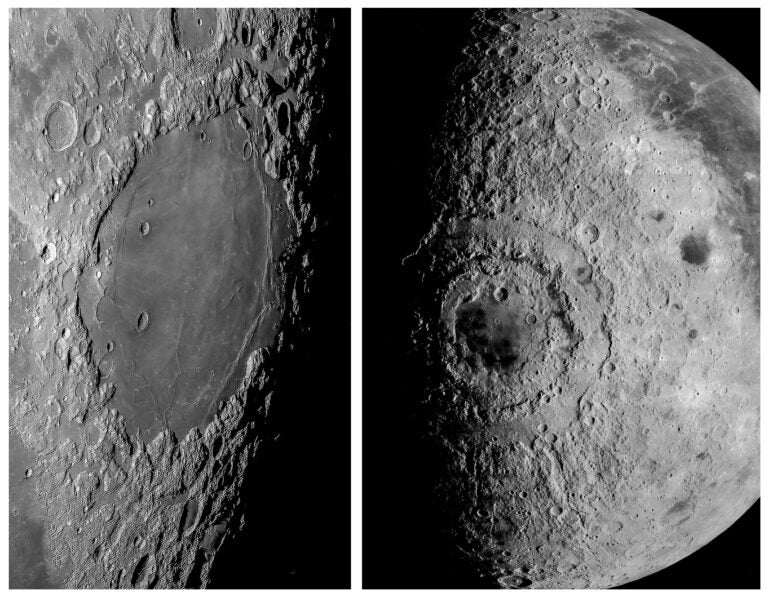

Saturn’s rings are the planet’s defining characteristic. From afar, they look like a vinyl record circling the yellow gas giant. But bring a camera close to Saturn, and the smooth disk resolves into belt after belt after belt, with spaces separating them. That was the view revealed by the Voyager flybys in 1980 and 1981, which led scientists to think the rings were probably made of tiny ice particles that slowly bump into one another as they orbit the planet.

Use Cassini’s instruments to watch as the rings filter light from a background star, however, and all of a sudden those belts become far more complex. The particles clump together and form bigger bodies. The gravity of those objects — boulders and minimoons — controls the rings, herding smaller particles and building structures and patterns. And they change quickly, says Larry Esposito, principal investigator on Cassini’s Ultraviolet Imaging Spectrograph, who has studied Saturn’s rings for more than four decades. “Structures develop within hours in the rings.”

Planetary scientists have identified several different types of structures. Some, which come and go and come back again, are called kittens — “because they seem to have multiple lives,” says Esposito. Others, called propellers, migrate slightly inward or outward. They are consequences of gravitational interactions between a small moon embedded within the rings and the ring particles themselves. The moon tries, unsuccessfully, to clear away the particles and create a gap.

Bigger moons tend to have more noticeable effects. Prometheus, for example, whose diameter averages 53 miles (86 km), “dips in almost to the edge of the F ring and pulls out streamers,” says Spilker. Several other moons also leave their gravitational imprints. Scientists had long known that Mimas creates the Cassini Division — like the spacecraft, named for the 17th-century Italian-French astronomer Giovanni Cassini — the broadest gap in the rings. But it took data from the Cassini probe to reveal that seven midsized moons combine to keep the outer A ring from dispersing.

Despite all the incredible ring structure that Cassini’s cameras and spectrometers resolved, scientists still have questions. The biggest one concerns the ring system’s mass. They don’t want to know this mass just for knowledge’s sake. Instead, the mass is linked to the age of the rings and how they formed.

This is important because Saturn’s rings are the closest example astronomers have of astrophysical disks — such as the flattened disks of gas and dust out of which solar systems form. “It’s not the same, but it’s analogous,” says Hedman. And this means, “if we don’t understand what’s going on in the rings, we could be missing things about, say, how the solar system formed.” The processes going on in the rings could give astronomers valuable insights into how planetary systems develop.

The Grand Finale data are getting scientists closer than ever to figuring out the rings’ mass. During those final months, Cassini flew between the inner rings and Saturn’s upper atmosphere 22 times. Throughout the previous 121/2 years of Saturn exploration, the spacecraft stayed outside the rings, and thus it felt the combined pull from Saturn and the rings. “When you are between the rings and Saturn, the rings are pulling in one direction, and Saturn is pulling in the other, so you can disentangle the two effects,” says Luciano Iess, who is leading Cassini’s gravity data analysis. Disentangling the two will not be easy, however. The preliminary analysis, he says, “seems to indicate that the rings did not form with Saturn.” It will take more research to firm up this result, and to find out when and how the rings formed.

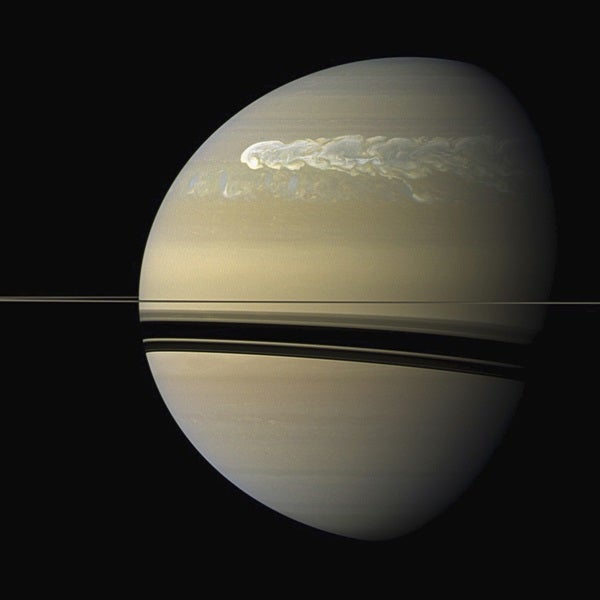

Beneath Saturn’s majestic rings lies the planet’s equally magnificent cloud tops. Cassini unveiled churning and swirling clouds in the upper atmosphere, and places where warm gases rise up through cooler layers and erupt into long-lasting thunderstorms. Cassini resolved these thunderstorm clusters into minute detail, watching them evolve and listening to the radio static from lightning flashes.

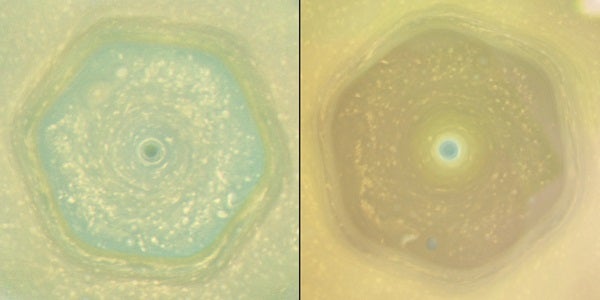

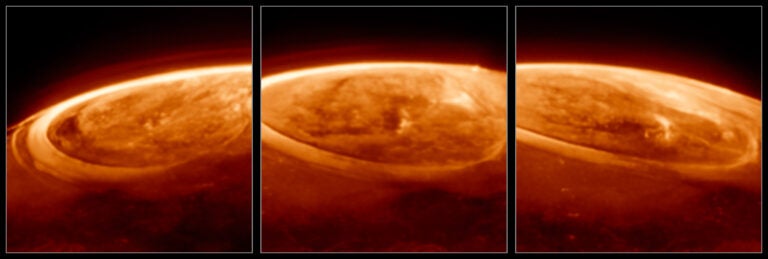

While normal photos painted pretty pictures of the whirling atmosphere, infrared images let scientists see below the cool cloud tops to warmer regions beneath. “And that’s our secret weapon for how to analyze the depths of Saturn,” says Cassini scientist Kevin Baines. “[It’s] how Saturn was revealed to be not this nice demure place, but this roiling dynamic place.” He and his colleagues watched as clouds in the upper atmosphere blocked heat from below. They also identified vortices and a giant cyclone at each of Saturn’s poles, though only the north pole features a hexagonal jet stream.

But one storm stood out from all the others. The Great White Spot erupted unexpectedly December 5, 2010. Earth-based observations of Saturn over the past 140 years had shown that a giant, long-lasting storm pops up every 30 years or so, alternating between cloud bands in the northern hemisphere and near the equator. In 1876, one appeared at the equator; in 1903, another developed at mid-northern latitudes; and in 1933, a storm emerged back at the equator. The pattern continued over the decades, and scientists expected the next storm would arrive around 2020 — after Cassini’s reign. But it fortuitously arrived 10 years early, and gifted Cassini scientists with an up-close look at how these giant storms evolve.

The jet streams in Saturn’s atmosphere carried the northern hemisphere storm along its cloud band. By late January 2011, it wrapped around the planet and stretched 9,000 miles (15,000 km) north-south. As the storm progressed, scientists used the imaging instruments and RPWS to view it. In summer 2011, after some 200 days of roiling, swirling, and spreading, the storm died out and the atmosphere cleared. The region, says Baines, “has been very boring ever since.”

Because scientists could watch the great storm evolve with Cassini’s broad array of instruments, they could piece together a coherent picture of what causes these long-lived events. Caltech’s Andrew Ingersoll and his then-graduate student Cheng Li put forth the most likely theory. They say it’s due to a convective competition between water-rich clouds and the lighter-weight atmosphere of mostly hydrogen and helium. The heavier, wet clouds can’t rise until the lightweight upper clouds become denser and sink.

But this competition is a marathon. “The air above has to cool off, radiating its heat to space, before its density is greater than that of the hot, wet air below,” said Li in a press release. “This cooling process takes about 30 years, and then come the storms.” Once the storm rains out its water content, convection shuts down, and the storm stops.

When you think of Saturn, the ornate rings and cloudy atmosphere likely come to mind first, but no object exists in isolation. So, how does the giant planet affect its surroundings? That’s where Saturn’s magnetic field factors in, and it’s why Cassini brought along instruments to study it and the region the field controls, called the magnetosphere.

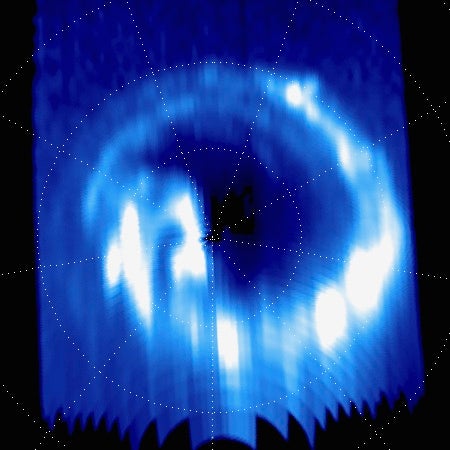

Previous observations of Saturn had shown aurorae at the planet’s poles, similar to the northern and southern lights seen in Earth’s polar regions. Cassini’s RPWS instrument monitored auroral activity by detecting the radio waves that aurorae generate, in much the same way it heard radio flashes associated with lightning. “We’ve been able to use the intensity of these radio emissions as a proxy,” says Kurth, to address questions of “how intense are the auroras and is there a lot of activity going on.” RPWS also monitored how Saturn’s magnetosphere and aurorae changed when the Sun delivered a burst of high-energy particles and radiation.

But how does Saturn produce its magnetic field? To find out, scientists used Cassini’s magnetometer. This instrument measures the strength and location of the planet’s magnetic field lines, which trace how charged particles travel. Electrons, for example, have a negative charge, and they always move toward a magnet’s positive pole. Both Saturn and Earth are essentially giant dipole magnets: They have a positive pole and a negative one. Each planet generates its magnetic field deep in its interior. For Earth, researchers have a pretty good idea of how it happens. “You have heat, you have convection taking place in the interior, you have rotation in the interior, and you have flowing electrical currents,” says Michele Dougherty, principal investigator of Cassini’s magnetometer. “All of those combine to give you the magnetic field that you measure outside the planet.”

To measure Jupiter’s day, for example, scientists track the magnetic axis and find it wobbles with respect to the planet’s rotation. The magnetic field’s axis and the rotation axis tilt relative to each other, and that wobble relates directly to how fast the planet’s core is spinning. The problem with Saturn, though, is that the two axes are nearly perfectly aligned. This makes it awfully hard to find that wobble.

The precise alignment also perplexes researchers because it implies that the magnetic field should be decaying — and scientists have seen no evidence of a diminishing magnetic field at Saturn. When Cassini flew close to Saturn during the Grand Finale, the magnetometer collected data about the magnetic field. “We really expected these Grand Finale orbits to clearly measure the tilt, and all we’ve been able to do so far is put a limit on it,” says Dougherty. The angle between the two axes must be less than 0.06°.

Mapping gravity’s pull

The magnetic field analysis isn’t the only one proving to be extremely complex and requiring precise calibration. Scientists also want to know about Saturn’s interior, and in particular, how the planet’s mass is distributed. To do that, they need to measure the planet’s gravity. That’s not as simple as it might sound. “There is no instrument aboard a satellite which can reveal the gravity field by itself,” says Iess. Instead, scientists passed radio signals between Earth and Cassini and measured the slight changes in radio frequency. Those changes arose from gravitational tugs of mass pulling on the spacecraft — the more mass, the bigger the tug. So Iess and his colleagues can use those tiny frequency changes to map the distribution of mass within Saturn. Because Cassini skimmed the planet’s cloud tops during its final months, it felt a stronger gravitational pull from those mass distributions, and was able to sense finer details.

Precisely understanding those Grand Finale orbits is crucial to the gravity analysis of Saturn. So far, the team has learned that theoretical models of Saturn’s gravity do not match the data. “The gravity field of Saturn is surprising,” says Iess. “We found Saturn has features that can be explained only by differential rotation,” meaning some portions or layers of the planet move at different speeds than others. The researchers still have more orbit trajectories to calibrate, and thus are still months away from a major announcement.

Revealing that the interior doesn’t align with models would be a fitting discovery from a mission that already has found so many surprises at the Saturn system. Cassini’s suite of instruments offered the flexibility that allowed scientists to make those discoveries. The mission’s scientists and engineers worked in sync for decades to perform what Spilker calls Cassini’s “intricate ballet.”

“It’s for the unknown, the unexpected,” she says. “That’s why you do science.”