At the time of their flybys, both craft brought incredible clarity to Jupiter and Saturn and their moons, which had previously been visited by Pioneers 10 and 11 and their more primitive cameras. At the time the Voyagers launched, there were no close-up images of Uranus and Neptune; two of our outermost planets were mysteries. The world waited for the spacecraft to fly past each planet and send back whatever treasures they found. Glimpses of the light teal of Uranus, the bright blue of Neptune, and those textured rings of Saturn infiltrated the nightly news and the collective consciousness.

“At the time, the mission was all over the news,” explains Voyager Project Manager Suzy Dodd. “In those days, the press came in person, and we would have these live press conferences every day from JPL.”

Each week, people watching the news would see the planets grow in size as each spacecraft got closer, and the public followed loyally along with the mission. Earthlings suddenly knew more about their home solar system, and that excitement bled into popular culture, especially science fiction. Just two years after the launch of the Voyagers, Star Trek: The Motion Picture was released, featuring a familiar spacecraft. In the film, they called it “V’ger.”

“The main thing people reference when they talk about Voyager in the media is Star Trek,” says Dodd. “V’ger, V’ger, they always say.”

When NASA designed Voyager, they knew that someday it would leave the solar system entirely and might be visible to alien civilizations — if there were any out there to intercept it. In Star Trek, the fictional Voyager 6 has encountered a sentient artificially intelligent species that gave the spacecraft the gift of self-awareness. By the time the crew of the Enterprise meet V’ger 6, it’s likely the craft had encountered several civilizations.

After the discovery of the parked spacecraft, Spock decides to venture inside and find out more about what exactly V’ger is. As he’s flying through the ship, he says, “Curious. I’m seeing images of planets, moons, stars, whole galaxies all stored here, recorded. It could be a representation of V’ger’s entire journey. But who or what are we dealing with?” What Spock is seeing is a recorded database of V’ger’s encounters. Before the missions had even reached Saturn, people were already looking to Voyager as our future interstellar emissary.

In perhaps the perfect blending of real life and science fiction, Star Trek’s Voyager 6 encounter is what scientists had dreamed of when they launched Voyager 1 and 2 into space.

Out there

Star Trek wasn’t the only sci-fi hit to jump on the Voyager bandwagon. In a 1994 episode of The X-Files titled “Little Green Men,” FBI agent Fox Mulder narrates the story of Voyager while visiting the Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico. He starts the episode, “On August 20 and September 5, 1977, two spacecraft were launched from the Kennedy Space Flight Center, Florida. They were called Voyager. Each one carries a message. A gold-plated record depicting images, music, and sounds of our planet, arranged so that it may be understood if ever intercepted by a technologically mature extraterrestrial civilization.”

Mulder is searching (as always) for evidence of extraterrestrial life, and the Golden Record containing a message from Earth, calling attention to our own existence, is a fitting parallel to his journey. In the episode, a classical music selection from the Golden Record plays while Mulder has a bizarre alien encounter in Arecibo.

The Golden Record in and of itself is a vessel for a mixture of popular culture and general documentation of what it’s like to be an earthling. There were musical selections from the likes of Chuck Berry and Beethoven; rights management prevented “Here Comes the Sun” by the Beatles from being placed on the record. (The Fab Four were in favor of the move; their record label, which owned the rights to the recording, was not.) The record also contained 116 photos and images of scientific concepts and daily life worldwide; a “hello” in 55 languages; a recording of human brainwaves; various sounds of our planet, both human and geologic; and countless other time-capsule sights and sounds. Etchings of Earth’s position, guided by the position of local pulsars, were included on the outer cover.

Carl Sagan, who was a member of the Voyager imaging team at the time, found the right colleagues to work on the record. Jon Lomberg, an astronomical artist, chose the images. Linda Saltzman-Sagan, a writer and artist, compiled the language greetings; Ann Druyan, an artist, handled the everyday sounds; Rolling Stone editor Timothy Ferris lent his particular support on the musical selections; and SETI founder Frank Drake lent to the project his vast knowledge of trying to home in on the best way to communicate with alien species.

Since the 1970s, the symbolism of the record has shown up in TV shows, film, and even clothing. The record even recently became popular again when a Kickstarter campaign to reissue the full Golden Record set received over $1 million in funding from 10,000 people wanting their own copy of history.

The shores of the cosmic ocean

While working on the Voyager mission, Sagan and Druyan created a TV show called Cosmos. The PBS show, which debuted in 1980, not only highlighted the beautiful intricacies of Earth, but it gave viewers a perspective about our place in the cosmos, coinciding with the mission’s journey toward Saturn. (Sagan and Druyan met while working on the Golden Record and married in 1981.)

The impact of the show on popular culture is so great, it’s hard to quantify, though one benefit is that Cosmos ultimately inspired an entire generation of scientists. Jim Bell, a planetary scientist at Arizona State University who worked on Voyager at the beginning of his career and would ultimately memorialize the mission in the oral history book The Interstellar Age, credits Cosmos with inspiring his career path.

“Voyager launched back when I was in high school, and the show Cosmos by Carl Sagan was enormously impactful,” he says. “It was the first time that science was on TV and being communicated by a real professional communicator who could speak the language of science and translate it.”

A mote of dust on a cosmic ocean

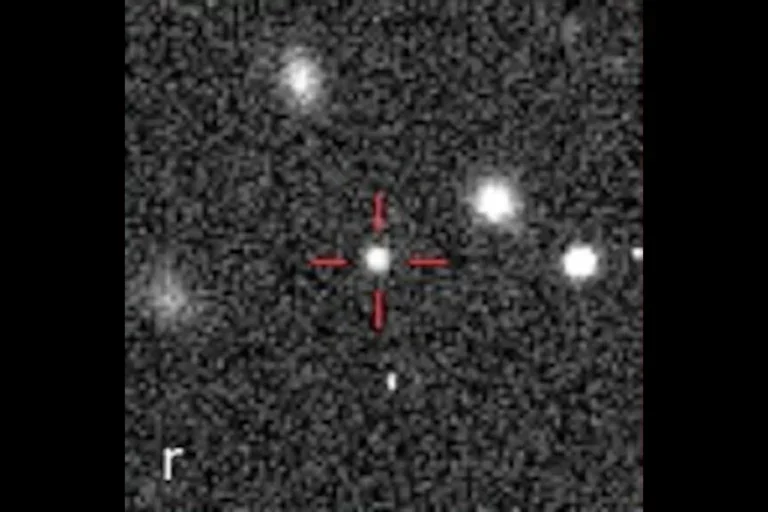

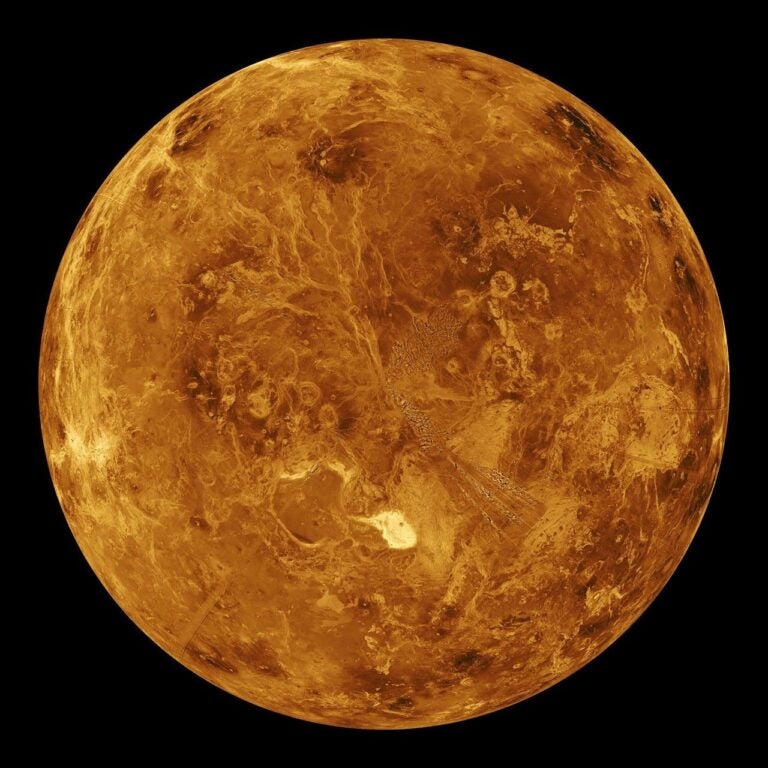

Perhaps more than anything else though, the biggest influence the Voyager mission had on popular culture came in the form of a single photo. The “Pale Blue Dot,” taken February 14, 1990, by Carolyn Porco and Candy Hansen at Sagan’s request, no doubt changed the world and how we saw ourselves. As one of its final images, Voyager 1 pointed its cameras toward Earth and snapped one final shot before the cameras were shut down to save power.

Sagan would later say the dot represented the human experience: “Look again at that dot. That’s here. That’s home. That’s us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives. The aggregate of our joy and suffering, thousands of confident religions, ideologies, and economic doctrines, every hunter and forager, every hero and coward, every creator and destroyer of civilization, every king and peasant, every young couple in love, every mother and father, hopeful child, inventor and explorer, every teacher of morals, every corrupt politician, every superstar, every supreme leader, every saint and sinner in the history of our species lived there — on a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam.”

As photos of Earth taken from space had done in the 1960s, the Pale Blue Dot put humanity’s place in perspective. We weren’t just one species uniting for our planet — we also weren’t the rulers of the universe, but rather an “insignificant planet of a humdrum star lost in a galaxy tucked away in some forgotten corner of a universe in which there are far more galaxies than people,” Sagan says.

“To my mind, there is perhaps no better demonstration of the folly of human conceits than this distant image of our tiny world,” Sagan says in Cosmos. “To me, it underscores our responsibility to deal more kindly and compassionately with one another and to preserve and cherish that pale blue dot, the only home we’ve ever known.”

The photo inspired Sagan’s book Pale Blue Dot, which, in turn, would go on to inspire short films like Wanderers and television shows like The Expanse with its grand vision of humans wandering from the cradle of our planet into the wider expanse of our solar system and, eventually, the universe.

The closest thing to the Voyager mission in the modern age may be the New Horizons flyby of Pluto. Today, we can search every major body in the solar system online and find an image of that object, but it wasn’t always that way. In 2015, the previously blurry dot we called Pluto became crisp with color, geological features and even a heart-shaped glacier, as the spacecraft undertook a six-month reconnaissance of the distant planet and its moons. Like the Voyagers, New Horizons’ discoveries help us understand Earth’s place in the cosmos.

“For the first time, we have the power to decide the fate of our planet and ourselves. This is a time of great danger, but our species is young and curious and brave. It shows much promise,” Sagan says in the first episode of the original Cosmos. “In the last few millennia, we have made the most astonishing and unexpected discoveries about the cosmos and our place within it.”

Thanks to the Voyagers and our continued exploration of the solar system, this statement still rings true. We know more about our place in space and can imagine other civilizations having an encounter with an artifact of humanity. Sometime around 2025, both Voyagers will go dormant. But they will always carry a cultural legacy that few robotic missions have before — or may ever again.