Aside from the therapeutic benefits, astronomy is one of the few hobbies where amateurs can actually advance the field by contributing variable star observations, novae discoveries, and the like. On another level, it’s just plain beautiful. And on a more practical note, unlike many hobbies, astronomy can be quite cost effective.

Unfortunately, anecdotally our hobby is graying and we’re a bit, well, testosterone heavy. It seems like fewer and fewer young people are becoming involved in astronomy. And that’s a point of concern.

I’ve been an educator for going on three decades, and I can tell you firsthand that it’s not without hope. I’m lucky enough to teach an elementary-level astronomy class (which typically runs every other year), and there is often a waiting list. Children are curious by nature. They want to know how the world works. If you have access to a 5-year-old, just listen to them sometime. They ask questions like, “Why is the sky blue?” and “What keeps the Moon from falling down to Earth?”

These deep questions get at the root of science and more — what it means to be human. Somewhere between birth and college graduation, though, we seem to stomp much of the scientific curiosity out of our children, at least outside the classroom. We, as adults, need to find a way to bring that wonder back. We have a generation that we can hand the hobby off to and rest assured that it’s in good hands, assuming we can cultivate that interest. So what can we do? The answer involves you, your time, and your love of the hobby.

Into the modern age

In a post-Apollo age marked by the invention of the personal computer, I somehow managed to get hooked on astronomy. Needless to say, I don’t really buy the argument that astronomy can’t compete for our children’s time. While it’s true that kids have a plethora of devices that buzz and light up, I think we can overcome those distractions. It may not be easy, but it will be rewarding.

You can start with getting involved on the school or afterschool level. Donations to programs, both in cash and equipment, are always welcome, but all too often things don’t work out like you’d want. I’m all too aware of cases where first-class equipment has been donated to a school district, but wound up just sitting in the closet. If you really want to get young people interested in astronomy, give the gift of your time.

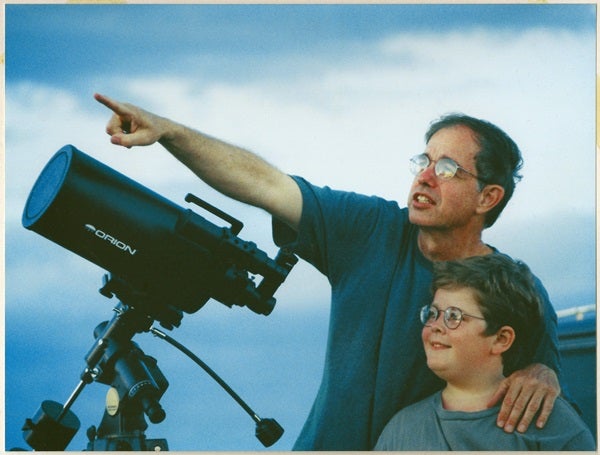

One thing I can’t recommend enough is setting your scope up for a neighborhood demo. Be prepared for touching: Kids (and even adults) have been known to get excited and do things like touch the lens or (gasp) grab the scope to help steady themselves. You may find yourself more relaxed if you have some gear reserved specifically for outreach.

If you can work with a child one-on-one, consider teaching them to operate your telescope, then standing back and letting them have their way with the night. There is nothing quite as exciting as learning to pilot your personal starship. But stick around to offer support and guidance. Lightly guided voyages of discovery often make the best impressions.

The next level up would involve setting up a scope in a public location to hold an impromptu star party. I’ve found Halloween is an excellent time to offer a celestial treat to the little ones — and some of the parents as well.

No kids in your neighborhood? Look for the nearest youth group and offer to run a session. Traditionally this group would have been Boy or Girl Scouts, but things have diversified over the last few years. Schools, churches, and communities all have programs designed for kids. Our local communities offer a plethora of programs through the Parks and Recreation Department. Scouting-type groups often have an astronomy merit badge — you can help teach it. Community colleges and universities often hold summer programming as well. One of my local colleges offers two-week outreach programs for youth. Many times they are afraid to offer astronomy because while they can handle the armchair portion well enough, they don’t have anyone who actually knows how to operate a telescope. Call up your group of choice and offer your experience.

Beyond the books

It’s easy to obsess over the numbers. (Example: The Andromeda Galaxy [M31] is 220,000 light-years across and 2.5 million light-years away.) When working with people, while it’s important to get the facts straight, never lose sight of the ultimate objective. It’s less important for you to know all the exact details about the craterlets in Plato Crater on the Moon than it is for the newbie to actually see the Moon firsthand and gain some understanding of what they are actually seeing. If people want intensive detail, they can do some independent research. When we do outreach, we’re not trying to give them a complete and total grasp of the subject, we’re trying to kindle an interest. We want to revive that sense of wonder that comes from getting a good look at the cosmos. Don’t get hung up on the numbers.

If you have a smartphone adapter, offer to help young observers snap a photo of the Moon using their phone. Not only may it cultivate an interest in astrophotography, but they’ll take it with them, right where they can show it to friends or use it as a phone background.

As for other bright subjects, Saturn and Jupiter are staples. Mars can be interesting if it’s at opposition (near to Earth). However, I’ve found most inexperienced observers are a little disappointed when viewing the Red Planet for the first time.

Getting out of the neighborhood

Bright deep-sky objects are also good choices. The Hercules Cluster (M13), is particularly neat if you have a large enough scope to resolve its stars. The Orion Nebula (M42) is an excellent target to inspire awe and wonder. With a medium-size scope, observers with young eyes may even see some color. The Dumbbell Nebula (M27) and the Ring Nebula (M57) seem to make a greater impression when you tell your guests they’re looking at a possible future for the solar system, explaining that even stars will someday die.

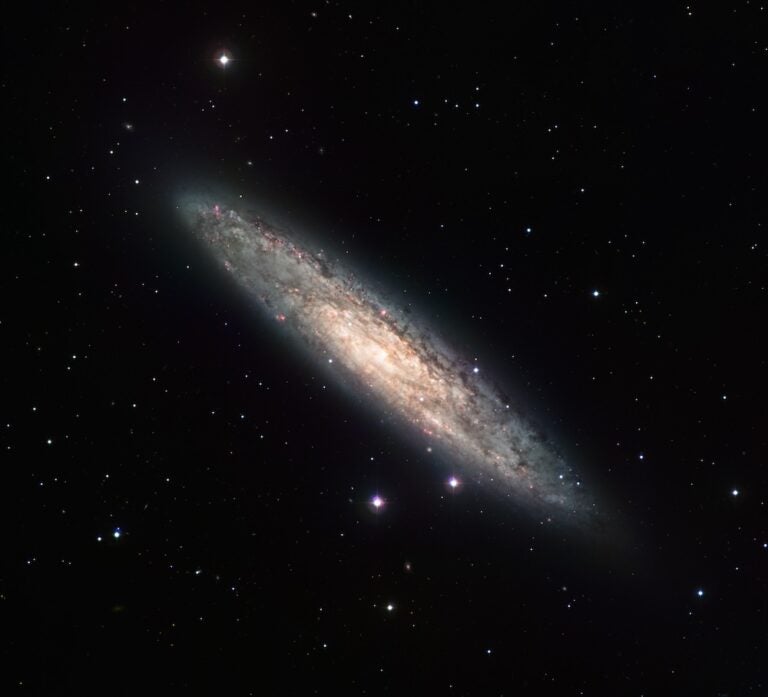

I tend to stay away from galaxies when showing newcomers the wonders of the sky. Faint fuzzies are just that — faint and fuzzy and often unimpressive to the newcomer. One exception is the Andromeda Galaxy (M31). I explain lookback time as we gaze up to the cosmos and stress just how old those photons are that are now entering our eyes.

Colored double stars and asterisms can be impressive as well. Albireo (Beta [β] Cygni) is always a great target, as is the Coathanger (Collinder 399). Consider a constellation tour, pointing out the figure, telling the story of the constellation and then leading a tour of a few impressive deep-sky objects.

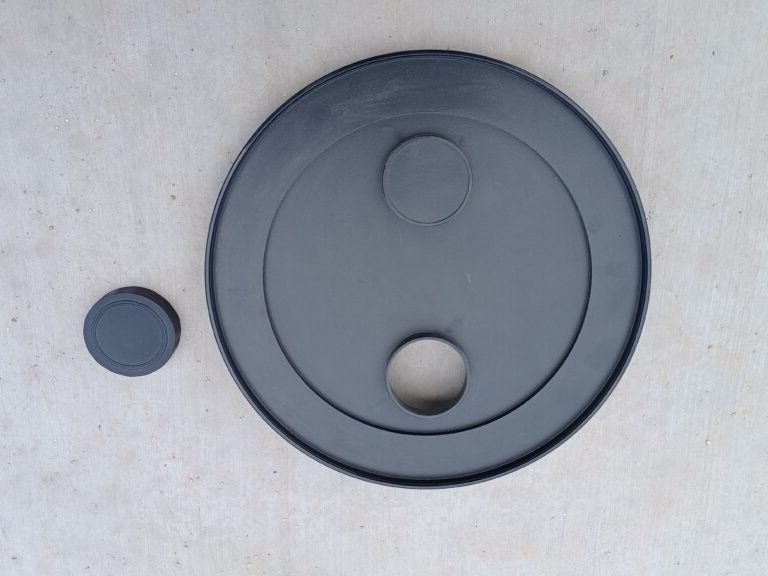

You don’t have to observe at night, either. Solar observing, with the addition of an approved filter, is an excellent option, and don’t overlook lunar viewing during daylight hours. It’s not nearly as impressive, but let’s face it — daylight is when most individuals are up and about.

Indoor fun

Observing isn’t always in the cards, but there are still other ways to get children interested in astronomy. For young kids, you might bake sheet cookies with constellations and stars marked by chocolate chips. If you’re teaching a classroom lesson, consider printing some blank star charts and letting the students create their own constellations, complete with backstory.

During the day, introducing kids to astronomy through virtual reality is a great idea as well, assuming the class size is small (one to three children) and you have the equipment. I’m fond of Titans of Space as an entry point. If you have access to a computer, you might spend some time designing and building space missions together in Kerbal Space Program. If the kids are more into the first-person perspective, NASA’s free Moonbase Alpha allows you to step into the role of an explorer in a futuristic lunar settlement. (Multiple computers are required for multiplayer games.)

If they’ve got internet access, kids might enjoy classifying galaxies through Galaxy Zoo (www.galaxyzoo.org), which gives you a chance to contribute to science and see objects that few folks have ever seen before. Galaxy Zoo is a subset of Zooniverse, which hosts a number of citizen science projects. It’s certainly worth a look. And if you’re struggling for what to do with a group of kids, NASA has a plethora of K-12 educational resources on its website.

The biggest thing that we, as amateur astronomers, can do to interest children in the night sky is the same thing we need to do to help them grow. We need to donate our time and our patience. And if you are able to donate equipment to your local school or youth group, don’t stop there. Take the extra step to ensure it’s going to be used. Gear is nice, but it’s people who make the difference.

Children are our hobby’s future. What seems like a small gesture on our part can have profound effects down the road.