Key Takeaways:

- Europa is considered a leading candidate for extraterrestrial life within our solar system, possessing the essential requirements of water, energy, and chemical building blocks, predominantly within a subsurface liquid ocean.

- Evidence for this subsurface ocean includes geological features observed by Voyager missions suggesting a decoupled surface, internal heating from Jupiter's tidal forces, and magnetic field anomalies detected by the Galileo mission indicative of a circulating, conductive liquid layer.

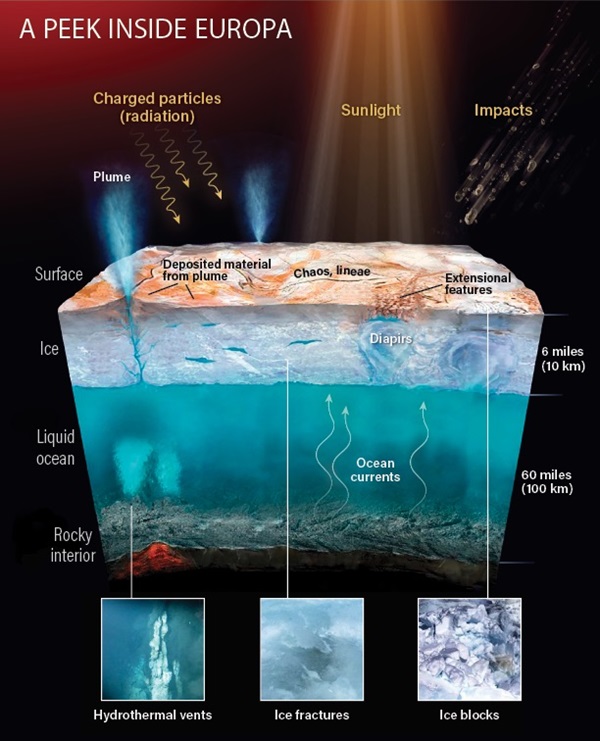

- Potential energy sources for life on Europa include hypothesized hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor, driven by tidal heating, and the breakdown of surface molecules by Jupiter's intense radiation, which could provide chemical reactants.

- Future missions, such as NASA's Europa Clipper, are designed to remotely characterize the moon's habitability, while proposed lander missions aim for direct detection of biosignatures on or near the surface, facing significant challenges in sampling and data transmission.

Europa, one of Jupiter’s four Galilean moons, is not the most welcoming place. On the surface, daytime temperatures barely surpass −260 degrees Fahrenheit (–160 degrees Celsius), and a fractured, icy shell blankets the landscape. Giant geysers occasionally blast water vapor 125 miles (200 kilometers) above the surface — the equivalent of about 20 stacked Mount Everests. If these conditions weren’t enough to deter visitors, intense radiation from Jupiter would doom any living thing on the surface.

Yet Europa is considered one of the best candidates to sustain life in the solar system. Despite its extreme conditions, the moon hits the trifecta of requirements for life as we know it: water, energy, and chemical building blocks. Although Europa is just one-quarter the diameter of our planet, it harbors a subsurface ocean twice the volume of the oceans on Earth. This aquatic environment, which has been stable for billions of years, may be a reservoir for life — and scientists want to find out whether it lurks beneath the surface.

Subsurface oceans

Life on Earth originated at sea, so it’s not a stretch to imagine life on Europa starting in a similar environment. The moon’s subzero temperatures prohibit surface oceans like ours, but scientists in the 1970s discovered an icy shell covering Europa. Studies of the surface ice show it is largely water ice with a smattering of related compounds like hydrogen peroxide, carbon dioxide, and sulfur dioxide. While the shell’s thickness is uncertain — best estimates range up to dozens of miles — scientists are certain that a liquid ocean circulates beneath.

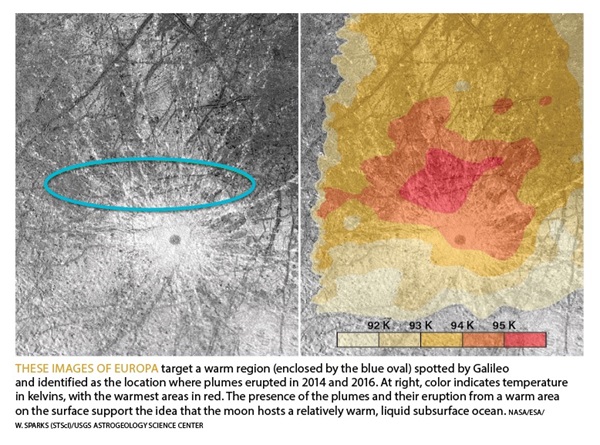

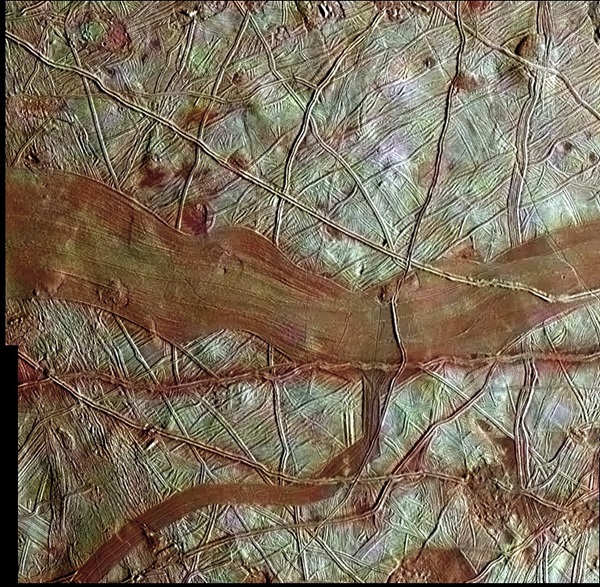

Voyager 1 and 2 took the first close-up images of Europa when they flew through the Jupiter system in 1979. The images showed a relatively smooth surface with few craters or mountains, but scratched with bands and ridges. The lack of large impact craters, which build up as meteorites strike a planetary body over millions or billions of years, meant that some process was erasing them. Separated ridges, where it looked as if icy material had gushed up between the walls, also suggested a geologically active world. Scientists observed long linear features that they determined could be created if the surface was disconnected from the moon’s interior — for example, with a liquid ocean sandwiched between them.

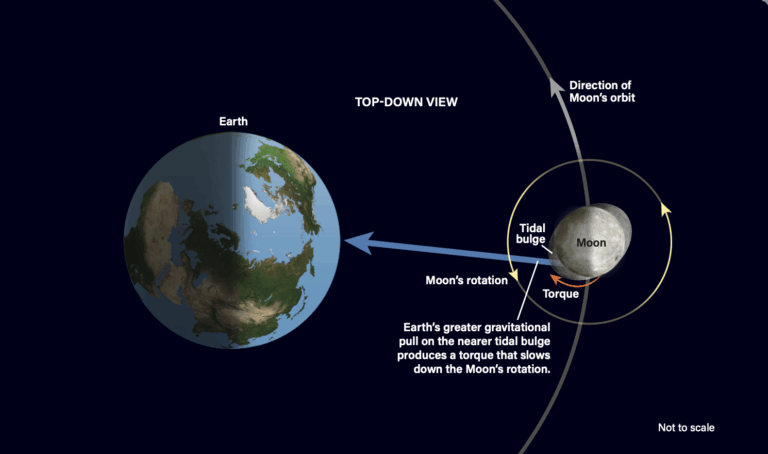

At about 485 million miles (780 million km) from the Sun, Europa does not receive enough heat to keep an ocean liquid. But it has its own heat source: Jupiter. As Europa travels in an eccentric orbit around its host planet, differences in the force of gravity from one side of the moon to the other squish and squeeze it. This friction is enough to heat up the moon’s solid interior in a process known as tidal heating. The heated rocky ocean floor could then maintain a liquid ocean and induce circulation below the crust of ice. If the ice shell is sufficiently thin in places, the heated water might even seep though, creating the jumbled surface of broken ice blocks astronomers see in images. Such heating could also generate the geysers blasting from the surface.

In 1989, NASA launched its Galileo mission to study Jupiter and the four Galilean moons — Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto — in greater detail. With 12 close flybys, the mission took new measurements that increased scientists’ certainty of a liquid ocean on Europa. Perhaps the most conclusive data from Galileo were the magnetic field measurements. As the spacecraft approached Europa, it observed a slight “bend” in Jupiter’s magnetic field, indicating that a second magnetic field is being created, or induced, within the moon. The most likely cause, researchers believe, is the circulation of an electrically conductive global saltwater ocean beneath the surface.

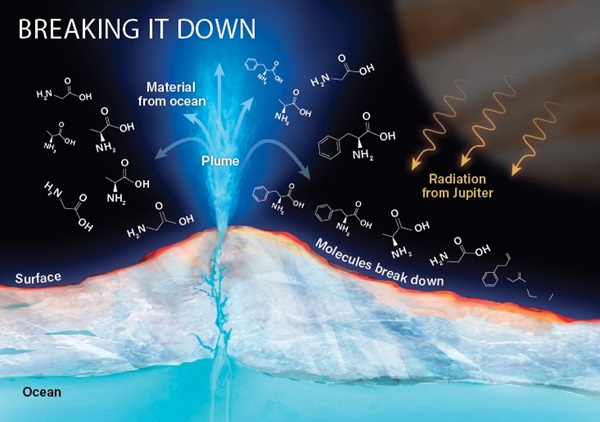

Europa’s surface could show signs of life if material containing biomolecules is ejected by the moon’s plumes. But because intense radiation from Jupiter breaks down materials on the surface, those signs could be erased, which is why researchers hope to take a direct picture of life rather than detect it through surface composition.

Astronomy: Roen Kelly, after NASA/JPL-Caltech

Microbial energy bars

In addition to water, life needs energy. Most life on Earth derives its energy from the Sun. Plants use the Sun’s energy directly, while we — and other animals — use the products they create. However, Europa’s harsh conditions likely relegate life below the surface, where the distant Sun doesn’t shine.

On Earth, microbes can live near deep-sea vents where warm, chemical-rich material bubbles up. Although no hard evidence yet exists, some scientists suspect that Europa’s tidal heating creates volcanoes and hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor, just as tectonic activity does on Earth. Providing more than just a heat source, any volcanoes or vents would also offer an important source of nutrients. The heat and activity in the interior would drive chemical reactions and bring up new material into the ocean. If Europa’s interior is highly active, there could be a large exchange of material, which would provide a steady flow of nutrients and even the chemical building blocks for life. Thus, determining just how active Europa is remains a key question for scientists investigating the moon’s potential habitability.

Above the surface, intense radiation from Jupiter also helps break down molecules. These chemical bits and pieces can then reform to create new compounds that could also be useful to microbial life. Open fissures on the surface might allow these compounds to eventually circulate below.

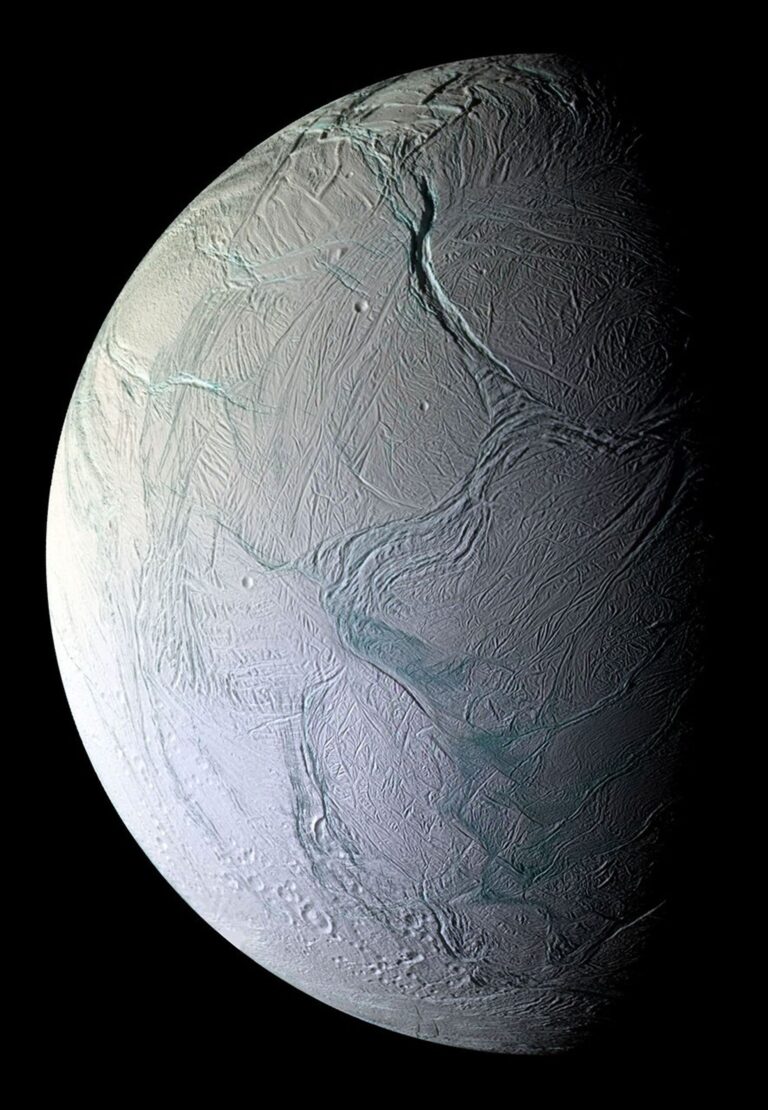

Europa’s icy crust contains a wealth of interesting topography that hints at the moon’s geologic past. This close-up image of the terrain, taken by the Galileo spacecraft, shows ridges, domes, and a jumbled area of “ice rafts” that scientists think broke away from their original locations. The smashed-up blocks of terrain are a compelling sign that the moon once had a liquid ocean.

NASA/JPL/University of Arizona

Gathering intel

Finding hard evidence of life is difficult — particularly on Europa, where it would likely lie under layers of ice.

“Biologists still struggle to put a definition on what is alive and what is not alive,” says Curt Niebur, a scientist at NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C. “It’s hard enough [searching for life] on Earth, so doing that halfway across the solar system with a robotic spacecraft is even more difficult, more complicated, and more challenging.”

Because of the seemingly uninhabitable surface conditions, any probe sent to the moon would theoretically have to drill down some unknown distance before sampling for life. Scientists are working on ways to achieve this, but in the near future, they’ll only be able to take measurements remotely.

Niebur is working on just that as the program scientist for NASA’s Europa Clipper mission, which aims to launch in 2023. By studying the moon in detail, the mission will determine whether Europa has conditions suitable for life.

Entering orbit around Europa, the craft will use nine instruments to investigate the moon’s surface and interior. At closest approach, Europa Clipper will speed by just 3 miles (5 km) above the surface, low enough to fly through geyser bursts. A mass spectrometer and dust mass analyzer will study particles ejected in the bursts, while an ultraviolet spectrograph will image the plumes from afar and identify their composition. Other instruments will look for thermal signatures on the surface to detect new bursts, while ice-penetrating radar will measure the thickness of the icy shell. A magnetometer will measure the strength of the moon’s magnetic field to probe its interior. These data will help scientists determine how deep the ocean might be, as well as its salinity.

Heat and materials from Europa’s interior might be released through hydrothermal vents on the moon’s ocean floors. Warm water rising toward the base of the icy shell could cause cracks and other features, such as diapirs, while large chunks of the surface — ice rafts — may detach and float to new locations. Plumes could spout the ocean’s contents high above the moon, while radiation, impacts, and sunlight can all cause changes on the ice from above.

Astronomy: Roen Kelly, after K. Hand et al./NASA/JPL

Proof in pictures

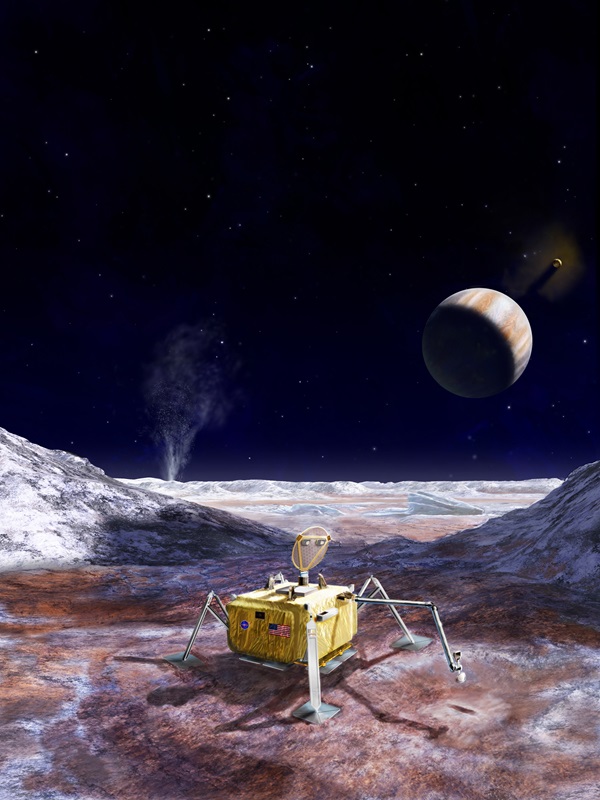

Ultimately, Europa Clipper will likely be able provide proof of habitability, but not signs of life. If selected, NASA’s proposed Europa Lander will follow after Europa Clipper and complement its mission by searching directly for biosignatures on the surface, as well as sampling the local composition of the moon.

Perhaps the best way to capture conclusive evidence of life on Europa is to take a photo. Scientists think their best bet is to equip the Europa Lander with a microscope for imaging water and ice samples.

Jay Nadeau, a biophysicist at Portland State University, and her collaborators are testing autonomous microscopes robust enough to withstand an interplanetary journey. They’re also developing a method of creating 3D images, similar to a hologram, with a camera that can simultaneously focus at multiple distances to avoid blurry images. However, such images generate a lot of data, and the proposed lander’s power supply and communications bandwidth for sending information back to Earth is limited. With multiple instruments vying for those necessities, Nadeau suspects they’ll have enough bandwidth to send back only a few 3D pictures. “There’s not much data you can send back from the mission, so we’re going to need a computer algorithm to say, ‘This picture is actually interesting and we’ll send it back to Earth,’” Nadeau says.

The first missions will likely only be able to take surface samples, which would show life that has been preserved in ice. To that end, Nadeau and her team have taken their test instruments to extreme locations in the Arctic. Through studying microbial life in 100,000-year-old glaciers, Nadeau is trying to understand what they might be able to see on Europa. These types of studies are helping her create better computer algorithms to look for life, dead or alive.

Sometimes cells [in glacial ice] can survive, but a lot of times they don’t, and you get dead microbes,” Nadeau says. But dead microbes can look a lot like inorganic specs of dust, so it’s more challenging to prove they were once alive.But how would we get at life below the surface? Some researchers have proposed a nuclear-powered drill that could melt its way down to an area shielded from the damaging radiation above the ice. According to recent calculations, protected locations could exist a foot (30 centimeters) or less below the surface. At higher latitudes, where the radiation is less intense, biomaterials could be preserved at depths as shallow as 0.4 inch (1 cm).

Along with a microscope and potentially a drill, the Europa Lander mission would carry other instruments, including seismometers to investigate subsurface structure and spectrometers to analyze surface material composition.

While it’s difficult to speculate whether life will be found on Europa, there is certainly cause to think it’s a habitable place. If the planned and proposed missions stay on track, we may have an answer within a decade. Regardless of whether Europa is habitable or not, our observations will turn up new and interesting aspects of the moon to study.

“If life didn’t arise [on Europa], that makes life on Earth all the more special,” Niebur says. “But if we find that life did arise, that frankly makes the universe all the more special.”