As a planet hunter, Endl is a member of a growing league of astronomers who seek other worlds like our own to answer basic questions: Do certain types of stars host only certain types of planets? What’s the frequency of rocky planets within a star’s habitable zone? Do the atmospheres of Earth-sized exoplanets contain biosignatures indicating possible life?

The exoplanet search is an exciting field. A generation ago, it was considered a career dead end. Now, Endl and his colleagues are zeroing in on the answers to those questions.

Endl and his colleagues find extrasolar planets using techniques simple in theory but painstaking in execution. The two most productive are the transit and the radial velocity methods. The transit method is well suited for space observatories like NASA’s Kepler spacecraft. It can stare at a field of stars for weeks while measuring any stellar brightness dip caused by a planet crossing in front of a star.

The transit method is limited to detecting planets whose orbital planes are aligned with our line of sight, presumably only a small percentage. The transit method has had success scooping up hundreds of exoplanet candidates because of Kepler’s ability to stare at thousands of stars at once.

The radial velocity method is more forgiving of observational gaps caused by daylight or poor weather and is thus better suited for Earth-based observatories. This technique uses spectroscopy to measure a star’s velocity changes. These changes occur because of a planet’s gravitational pull on its star. This works well for many stars, but massive ones are not affected much by the pull of small Earth-like planets. When a planet is detected, the radial velocity method can also be used to determine its minimum mass.

Endl has been spent 20 years using radial velocity to find exoplanets. “Today, the existence of exoplanets is no longer in doubt,” he says proudly. “The discovery rate is not as important as characterizing the known exoplanets. The goal of our research is to find the difference between the planets around M-type, G-type, and supergiant stars. Rocky planets seem to be plentiful, but we want to determine if Jupiter-sized planets are the rule.”

Exoplanet science at McDonald Observatory

The University of Texas exoplanet program is but one of many searches worldwide. It began in 1988 and routinely observes a set of 200 nearby stars with the 2.7-meter Harlan Smith Telescope. It targets nearby suns across all stellar classes. Another 250 stars are the targets of the 10-meter Hobby-Eberly Telescope at McDonald Observatory in West Texas.

Small M-type stars are popular search targets because they are more abundant than G-type stars like our Sun. Endl explains more advantages: “Being smaller, their radiation is less intense, and their habitable zone is closer to the star. Planets circle M-type stars in several days, and the star’s lower mass responds more readily to the planet’s gravitational perturbations, making them easier to detect. A planet close to an M-type star can even be detected in one multiday observing run.” Although planets around M-type stars may be relatively easy to find, Endl emphasizes that long-term observations are necessary to refine masses and orbital periods.

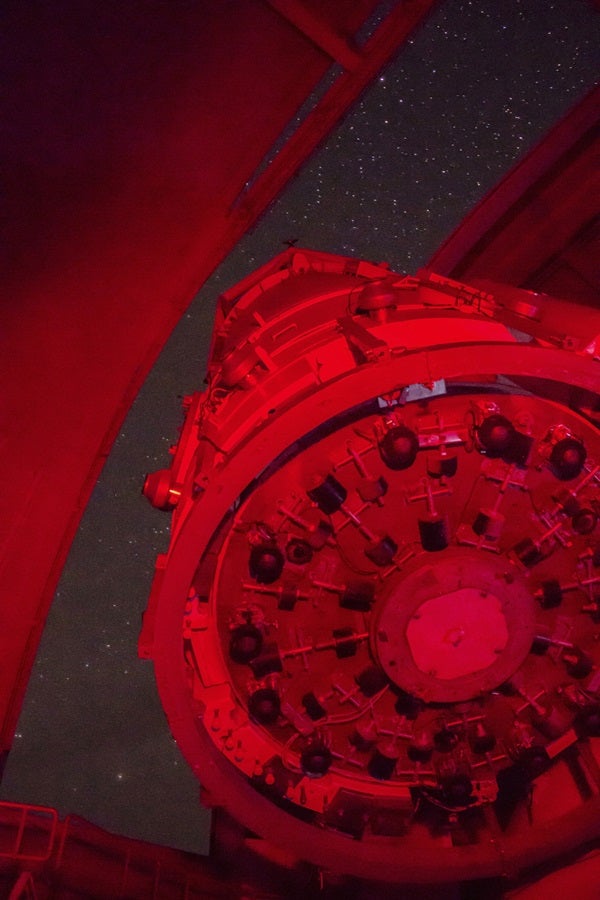

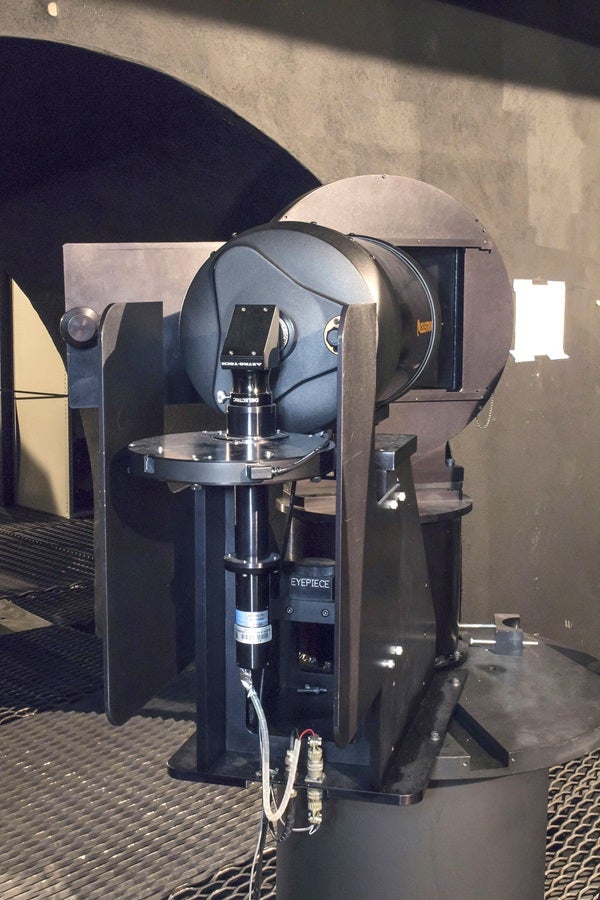

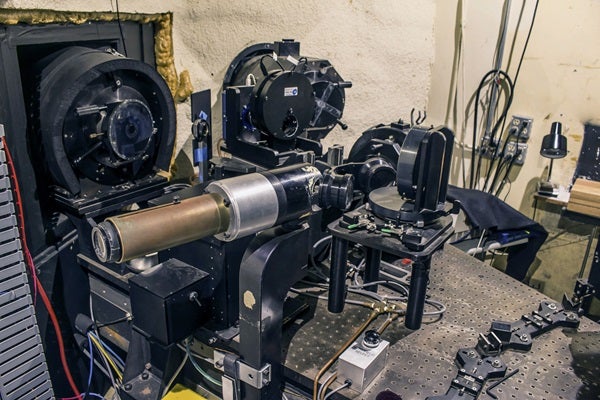

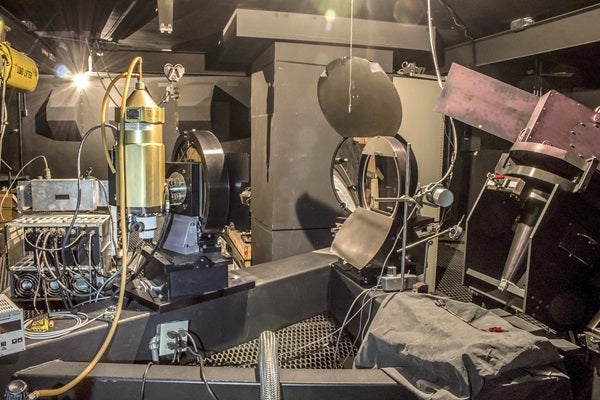

The Harlan Smith Telescope was built in the 1960s with help from NASA to support the Apollo program. The telescope can be configured to feed light into a massive spectrograph that takes up the entire floor under the telescope. It is well suited for recording spectra for radial velocity detection.

Exoplanet search time occurs during the brighter Moon phases because moonlight has little effect on spectra. Most targets are naked-eye stars, but some are as dim as 10th magnitude. The spectrograph is sensitive enough to measure radial velocities down to 4 meters per second, allowing detection of a Saturn-sized exoplanet 5 astronomical units from a Sun-like star. (An astronomical unit is the average Sun-Earth distance.)

Endl’s turn with the Harlan Smith Telescope comes every four months. Last summer I joined him at McDonald Observatory while he searched for exoplanets. Endl emphasized several things: “Important aspects of an observing run are good coffee and good music.”

As we listened to his eclectic playlist and sipped exotic coffee, I quickly deduced that finding exoplanets is not easy. There are few “Eureka!” moments when an observer spots a planet and quickly confirms it. Exoplanet searches require gathering extensive data that are analyzed over time to prove or disprove the existence of a planet around another star.

The spectrograph exposures are limited to 20 minutes, not because the sensor will become saturated, but because Earth’s motion smears the spectra and makes the star’s radial velocity hard to calibrate. Because denser layers of air absorb and distort starlight, no stars are observed below about 25° altitude.

The observer controls the telescope. The desired target stars are listed in a software script that selects the next star after each spectrum is recorded. An efficient autoguider built into the spectrograph slit guides the telescope during the exposure. A light meter within the optical path counts the photons and determines when a sufficient exposure has been recorded, often terminating the exposure before the 20-minute limit. If the star is as bright as 4th magnitude, the exposure is only a minute long.

When an exposure finishes, the telescope does not automatically move to the next target. The operator must exit the control room, walk to the telescope and dome control desk, and hold down a dead man’s switch to move the telescope. This keeps eyes on the telescope to prevent possible collisions with either the pier or objects on the dome floor. The operator returns to the control room and may record as many as 30 spectra per night.

The spectrograph’s CCD detector remains continuously below –100° Celsius (–148° Fahrenheit), cooled with liquid nitrogen. An operator calibrates the detector each evening with a thorium-argon emission lamp to match specific emission lines to specific pixels on the detector. The operator can adjust the position of the spectrum on the CCD detector vertically by tilting the prism and horizontally by tilting the diffraction grating.

A stellar radial velocity of 1,500 meters per second will shift a spectral line by one pixel on the CCD detector. The small stellar radial velocity shifts induced by a planet’s gravity cannot be seen through visual comparison of the spectra. The spectrograph data reduction software measures radial velocity shifts to the nearest 0.002 pixel, allowing the telescope to detect 4-meter-per-second stellar velocity shifts.

The spectrograph’s CCD detector is so sensitive that operators are forbidden from turning on fluorescent lights in the room because lingering emission will affect the instrument’s observations. Even incandescent lights cannot be turned on several hours before calibration or observations.

Light refracts differently as Earth’s atmospheric pressure and temperature change, altering the spectrograph calibration. To offset this, equipment keeps the telescope and spectrograph room at the same temperature. As the spectrograph creates an image, an iodine reference spectrum is simultaneously recorded near the star’s spectra. This anchors known spectral lines to known pixels in the spectrograph, allowing spectral shifts induced by telescope flexure and atmospheric conditions to be removed.

Unlike other large professional telescopes, the Harlan Smith Telescope has a closed tube. A ventilation system stabilizes the temperature in the telescope, allowing it to routinely achieve 1″ resolution.

Next, the two collaborators determine if the candidate star’s periodic dimming is due to factors such as a binary companion, intrinsic variability, or large “starspots” on its surface. If such options are ruled out, more follow-up observations search for the telltale radial velocity curve indicating the star is slowly drifting back and forth along our line of sight because of the minute pull of a planet’s gravity.

A bright future

Years of research indicate that planetary formation is a robust mechanism. Kepler data suggests that 30 percent of Sun-like G-type stars have 1 to 1.5 Earth-radii planets within their habitable zones. However, the statistical error could be as much as 20 percent; thus, Earth-like planets could be as rare as existing around only 10 percent of G-type stars or as plentiful as circling half of them.

Hot Jupiters orbiting close to their stars are rare. Researchers wonder whether such planets have migrated inward, destroying the rest of their star’s planetary system. They would also like to know whether Jupiter-sized planets are a normal part of planet formation.

Understanding an exoplanet’s atmosphere is also a key area of research. The current problem is that the spectrum of the atmosphere of a transiting planet is a fraction of the star’s total spectrum. Present-day techniques can analyze the rough atmospheric composition of transiting planets with 1.5 to 2 Earth masses, as well as the hot Jupiters that lie close to their stars. However, many of these exoplanets have a hazy atmosphere whose spectra reveal little about it.

Of course, astronomers would like to detect biosignatures — gases produced as a byproduct of life. To do this with today’s technology would require a 30 m telescope or a space mission. Perhaps the Giant Magellan Telescope under construction in Chile will be able to detect biologically produced gases in the atmospheres of planets orbiting the nearby stars Proxima Centauri and TRAPPIST-1. Direct imaging of a non-transiting exoplanet will be more efficient at detecting biosignatures, but such searches will have to wait until the James Webb Space Telescope launches in spring 2019, or when the WFIRST satellite comes online in the next decade.

In the meantime, researchers like Endl continue their detective work by scanning nearby stars and refining techniques. With each new observation, Endl fills in the blanks and comes closer to answering the persistent questions about planets far beyond our solar system. Endl’s dream of creating the exoplanet chart is getting closer to reality. His current research will be the facts of future textbooks that describe amazing alien worlds undreamed of several decades ago.