Key Takeaways:

- Evidence suggests a subsurface ocean on Pluto, supported by surface fractures indicating global expansion potentially caused by ocean refreezing, the absence of an expected fossil equatorial bulge, and the mass excess in Sputnik Planitia consistent with a subsurface ocean causing true polar wander.

- Pluto possesses energy from radioactive decay within its rocky interior, sufficient to potentially melt ice multiple times; organic molecules are present in its atmosphere and on the surface, though transport to a subsurface ocean is unclear.

- The location of Sputnik Planitia, directly opposite Charon, implies a mass excess, possibly explained by a combination of nitrogen ice filling and ice shell thinning beneath, revealing a denser, water-rich layer.

- While direct confirmation of a subsurface ocean requires further investigation, the available geological and gravitational data, along with theoretical considerations, strongly suggests its presence beneath a thick, potentially rigid ice shell.

Despite decades of Earth-based observations, scientists knew little about Pluto until New Horizons studied it intensively, if only briefly, in 2015. The images it returned showed an unexpectedly diverse and active world, with mountains and rift valleys, glaciers of solid nitrogen, and a thin, hazy atmosphere.

Is it habitable?

Scientists typically assess the habitability of an environment in terms of the energy, organic molecules, and liquid water available. Pluto undoubtedly has the energy. Even before New Horizons, astronomers knew Pluto’s density well enough to deduce that it is roughly two-thirds rock and one-third ice by mass. Just like on Earth, radioactive decay within the rocks releases heat over geological time. This is Pluto’s dominant energy source, and it provides enough heat to warm the rocks in its interior close to their melting point. Other sources of heat, such as the gravitational energy released as the dwarf planet formed, are smaller but might contribute additional warming. Scientists don’t know whether the radioactive decay drives the kind of chemical interactions between water and rock we see at Earth’s midocean ridges, but it’s clear Pluto has substantial available power.

The dwarf planet also possesses organic molecules. The atmosphere contains about 0.3 percent methane. More importantly, New Horizons found that solar ultraviolet radiation splits these methane molecules apart and produces various simple hydrocarbons, including acetylene, ethylene, and ethane. Methane ice also appears on Pluto’s surface, as does a reddish material that is probably hydrocarbon haze particles settling out from the atmosphere. So the surface, at least, contains organic molecules that could provide the feedstock for life. Although it’s not clear there’s any mechanism to transport these molecules down to a possible ocean, studies of comets show that the interiors of outer solar system objects also can be rich in similar components.

An ocean on Pluto?

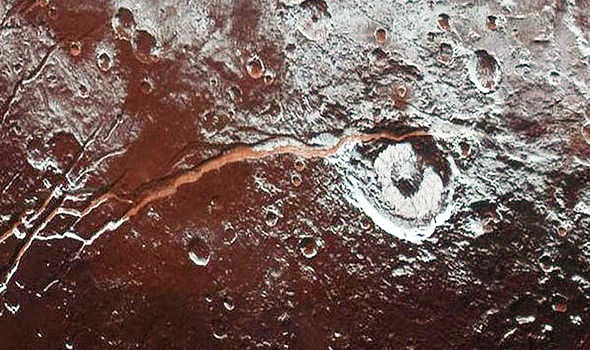

Three main lines of evidence point to a possible subsurface ocean on Pluto. The first comes from observations of the dwarf planet’s surface geology. One particularly striking aspect is the many enormous cracks or fissures that score the surface. These faults — some of which chop through older impact craters — imply Pluto has undergone a small degree of global expansion. One way to produce this planetwide swelling is to refreeze a subsurface ocean. As the water cools and converts back to ice, Pluto’s volume would increase and push the surface outward. The expanding ice shell also would press down on the water beneath, pressurizing it. If the pressure grows large enough, the water might squirt out to the surface in eruptions that scientists call “cryovolcanism.”

Saturn’s small moon Enceladus exhibits active cryovolcanic eruptions, but the evidence at Pluto is much less clear-cut. Two large structures with central depressions and strange, scalloped flanks could be cryovolcanoes, though not all of the New Horizons team is convinced of this. And some of the large fractures exhibit halos of unusual color and composition that could be a sign of material erupted from the interior, though again, not everyone accepts this interpretation. While the geological evidence is ambiguous, both the fracturing and the putative cryovolcanoes are at the very least consistent with what scientists would expect from a slowly refreezing ocean.

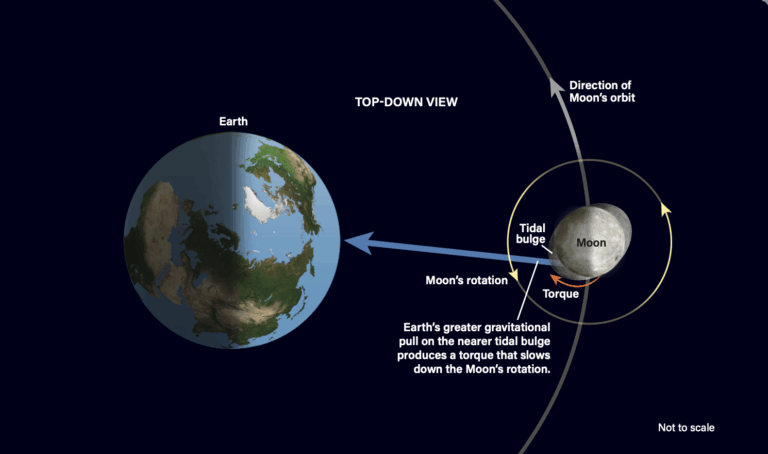

Pluto seemed a likely candidate for such a fossil bulge because it must have spun down considerably over time due to the gravitational influence of its large moon, Charon. Yet New Horizons failed to detect any such bulge. Although scientists have come up with several possible explanations, one sure way to remove a bulge is by developing a subsurface ocean — the ice shell above is simply too weak to sustain the bulge, and it collapses.

The heart of the matter?

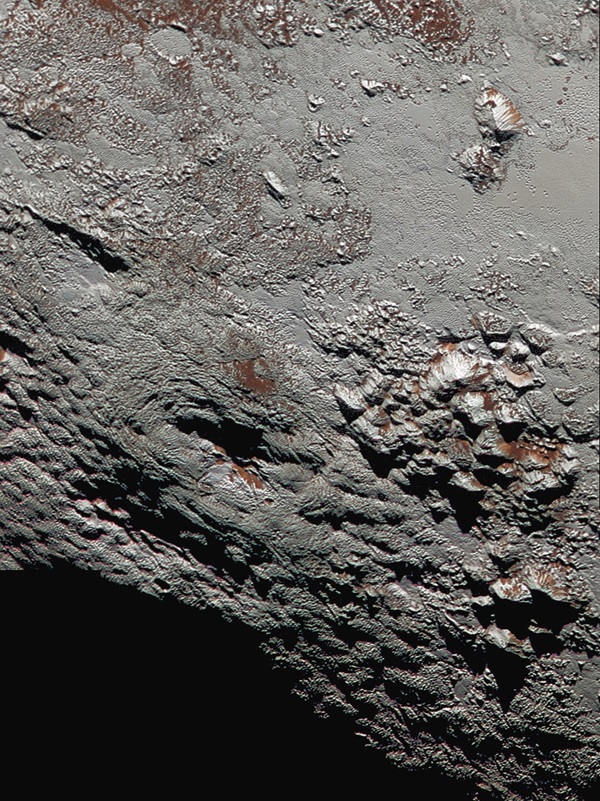

The last line of evidence is the most complicated, but also the most intriguing. It starts with the enormous, bright basin known as Sputnik Planitia. This region appears bright because nitrogen ice fills it, supplied by nitrogen glaciers that flow down from the surrounding highlands.

Another key fact about Sputnik Planitia is its location. It lies almost directly opposite the point on Pluto that continuously faces Charon. (Pluto always presents the same face to Charon, and vice versa.) If you could somehow place an extra mass, like a large mountain, on Pluto’s surface, it would cause the planet to roll over until the mountain reached Sputnik Planitia’s location. Scientists call this process true polar wander, or TPW.

One consequence of TPW is that Pluto’s surface gets distorted in response to the movement of the excess mass. This, combined with the surface expansion, produces fractures — and the observed fracture orientations match those predicted by computer models rather well.

So, Sputnik Planitia’s location makes perfect sense if it represents an area of excess mass. But how could the basin achieve this extra mass? After all, it is a hole in the ground. It helps that solid nitrogen is slightly denser than water ice, so filling the basin with nitrogen ice assists a bit. Except in the case of implausibly thick nitrogen layers, however, that contribution alone is not enough. One explanation points to a thinning of the ice shell beneath. A thinner shell means denser water has replaced lighter ice, causing an excess of mass. This combination of nitrogen loading from the top and a thinned ice shell beneath can easily produce a mass excess and cause TPW.

So, New Horizons has provided three lines of evidence that a subsurface ocean might be present on Pluto: the surface fractures and possible cryovolcanoes; the absence of a fossil equatorial bulge; and the requirement that Sputnik Planitia represents a mass excess. None of these is bulletproof, but taken together with the theoretical expectation that an ocean could be present, the odds seem to favor the existence of such an ocean.

How can we confirm an ocean?

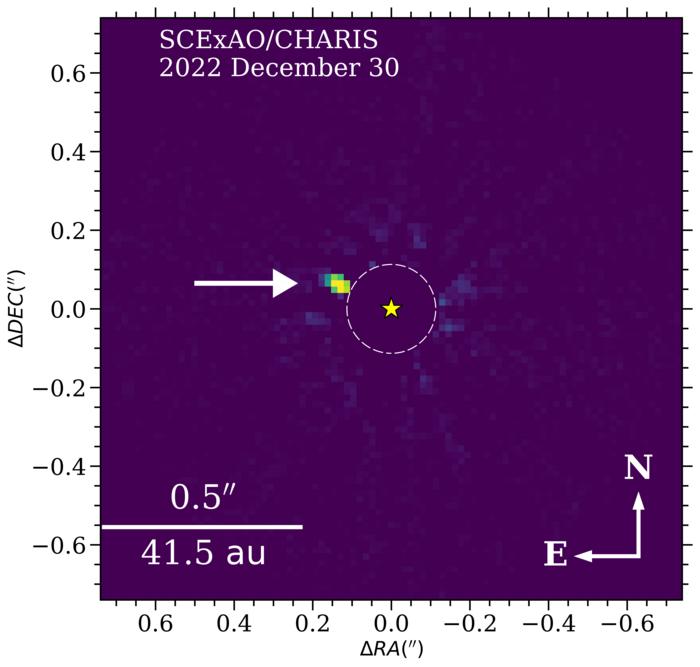

Over the past two decades, scientists have used several techniques to look for subsurface oceans on icy bodies. Unfortunately, neither of the two best methods will work on Pluto. The first requires a large background magnetic field, which induces currents in a body’s salty, electrically conductive ocean. Researchers then look for a secondary magnetic field generated by these currents. The technique has worked well on the moons of Jupiter, but there’s no large background magnetic field at Pluto to produce such a signal. The other method relies on measuring the size of a body’s tides, because large tides indicate a weak, and possibly liquid, interior. But Pluto and Charon always present the same faces to each other, so they effectively produce no tidal signal.

So, just how habitable is Pluto?

Pluto has a warm interior, organic molecules (at least on its surface), and most likely a subsurface ocean. So the dwarf planet probably meets the basic requirements for habitability. This is not to say that Pluto is a haven for life, because the degree of interaction between the ocean and the layers above and below it may be small. Although a fractured rocky core might efficiently transfer heat and perhaps organics to an ocean above, we don’t know this to be true. And if the only source of organics is material drifting out of the atmosphere, the shell would need to be in motion to supply them to the interior — and the available evidence indicates the shell is cold and rigid.

So Pluto is not as tempting a target as Europa or Enceladus, which have oceans topped by thin, mobile ice shells. But it might be a more suitable habitat for life than the large moons Titan or Ganymede, where a thick, high-pressure ice layer blocks direct contact between the ocean and the rocks below.

Pluto generates enough heat to comfortably sustain a subsurface ocean over billions of years. The evidence scientists have accumulated so far suggests such an ocean is present — although it most likely remains locked beneath a thick, rigid shell — and would be detectable by a future orbiter. Also keep in mind that Pluto is not unique: Other bodies in the Kuiper Belt have similar sizes and most likely also possess oceans. So, the outermost reaches of our solar system are not universally hostile. Despite the cold and the dark, Pluto and its brethren may represent welcoming oases.