Key Takeaways:

Historic Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, is commonly associated with two notable astronomical bodies: Mars and Pluto. Percival Lowell, who was determined to study the Red Planet and its putative canals, established the observatory in 1895. Its centerpiece was the legendary 24-inch Clark refractor.

Lowell was convinced that the illusive canals were built by intelligent beings to irrigate the deserts of a dying world. In addition to indulging such fanciful notions, however, Lowell was also an innovator and competent mathematician who posited a trans-Neptunian planet and was determined to find it. He initiated several photographic searches for “Planet X,” but sadly he did not live to see the success of these efforts. Clyde Tombaugh discovered Pluto in 1930, 14 years after Lowell’s death.

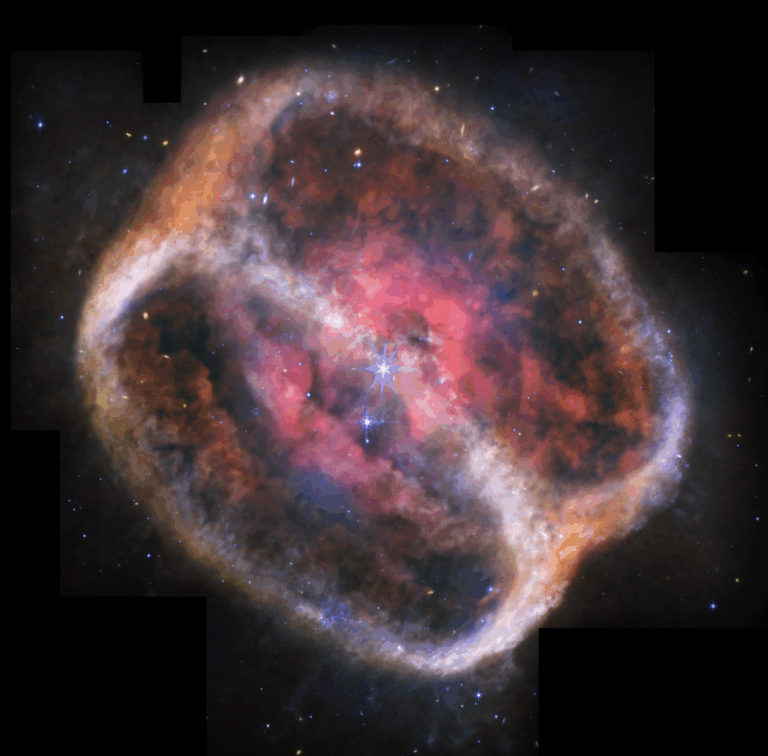

Amid all these undertakings, it is easy to forget that in the first half of the 20th century, the observatory and its great refractor were at the forefront of many other scientific discoveries. Notable among these were Lowell astronomer Vesto Melvin Slipher’s first spectra of spiral “nebulae” (later determined to be galaxies), showing that most were moving away from Earth and thereby setting the stage for Edwin Hubble’s discovery of the expansion of the universe. Slipher also discovered via spectroscopy that the Merope Nebula in the Pleiades radiates by reflected light rather than emitted light, thereby confirming the presence of the interstellar medium.

These advances led to the production of far better and more versatile refracting telescopes, as exemplified by Fraunhofer’s legendary 9.5-inch Great Dorpat Refractor in 1824. In the mid-1800s, Louis Daguerre and others developed the first photographic methods, which were quickly applied to astronomical objects. By the time Lowell founded his observatory, the preceding technological advances made much of the pioneering work there possible.

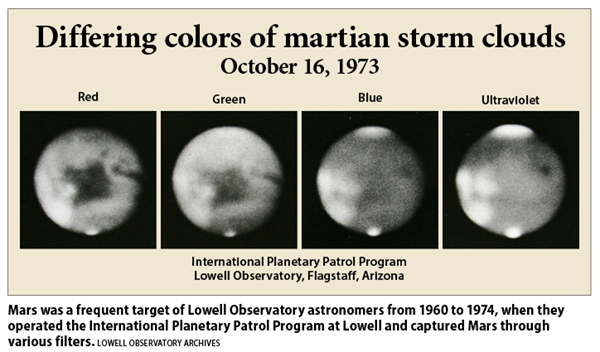

Notable in this regard was Lowell’s judicious application of photography to study the planets. He primarily attempted to photograph his controversial martian canals, to prove beyond any doubt they were “real” and not just illusive features visible only to Lowell’s eyes. Although the results were anything but convincing, subsequent work by two Lowell astronomers — Carl Otto Lampland and Slipher’s younger brother Earl C. (E.C.) Slipher — continued and perfected planetary photography well into the 1960s. Lampland was a skilled craftsman who developed novel instrumentation, including specialized cameras for the Clark refractor to facilitate large-scale, multi-image capture on a single photographic plate. He and E.C. Slipher also pioneered color filter photography to highlight different levels and compositional features of the atmospheres of Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn.

Into the modern age

The arrival of the Space Age in the late 1950s heralded renewed interest and research in lunar and planetary astronomy. Lowell Observatory and the venerable Clark refractor again played central roles. Two NASA-funded programs were initiated at that time, both centered on the observatory and partner institutions. One was the International Planetary Patrol Program (IPPP), and the other was the Lunar Aeronautical Charts (LAC) project.

The IPPP, led by Lowell astronomer William Baum, involved several observatories worldwide and was designed to constantly monitor the major planets photographically whenever they were favorably placed for observation. The goal was to garner as much information as possible on atmospheric, weather, compositional, and physical characteristics of each planet, in preparation for space probe missions to them.

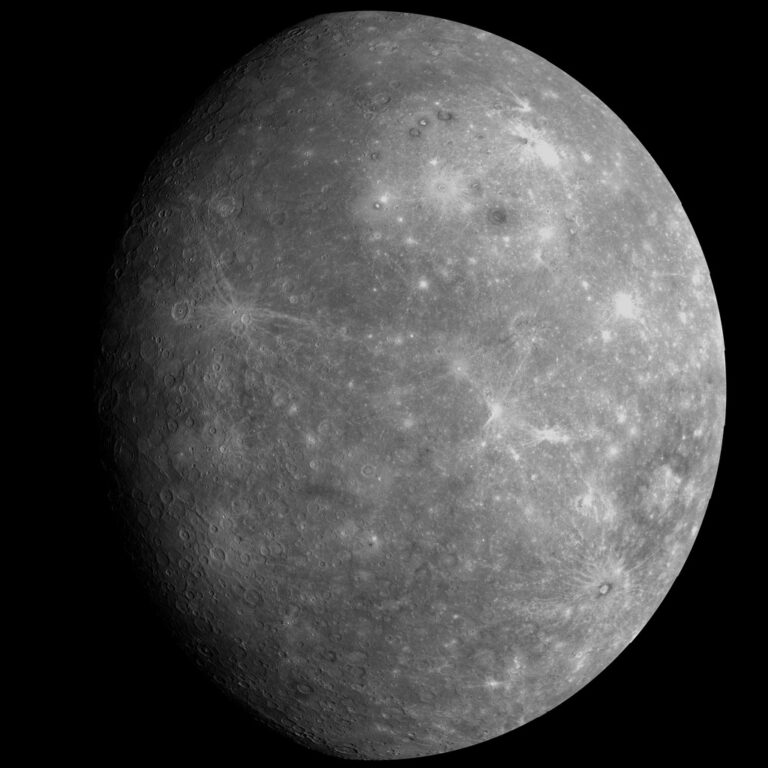

The Clark refractor’s last major scientific contributions did not involve direct photography, but provided visual backup for astronomers, geologists, and cartographers involved with the LAC project in preparation for the Apollo and early spacecraft era. This project combined the best available lunar photographs from Mount Wilson, Lick, McDonald, Yerkes, and Pic du Midi observatories, with visual observations obtained with the Clark telescope. The latter resolved far finer lunar detail than the grainy photographs of the time could record. The LAC series charts produced in the early 1960s thus marked the culmination of Earth-based lunar mapping efforts.

Today, the Lowell refractor is completely dedicated to public outreach and education, and it has enchanted hundreds of thousands of visitors over the decades. As a participant in that educational effort, I have been fortunate to try digital imaging through this classic telescope. I was particularly interested in seeing how well my results compared to the film-based images of yesteryear, and more specifically to the best lunar charts of the pre-Apollo era.

My first go at planetary imaging with the Clark was in October 2003 when Saturn was exceptionally well placed with nearly wide-open rings. Webcams weren’t popular yet, but at the time, I really needed a larger sensor to accommodate the image scale that a telescope of 9,770mm focal length produces. My choice was a Nikon Coolpix 995 camera with a (then-impressive) 3.3-megapixel CCD sensor and 4x optical zoom. I took some half-dozen exposures in quick succession and then stacked them in an early version of RegiStax.

Although seeing conditions were well above average that night, I soon discovered a more serious limitation — chromatic aberration. At the relatively fast f/16 focal ratio, the classic achromat exhibits considerable secondary color. Since the telescope is equipped with a front-end iris diaphragm, even closing it down to 18 inches left diminished, but still evident, purple color fringes. Of course, it’s important to realize that at the time of its manufacture in the late 1800s, the refractor was corrected principally for visual observations and not color photography.

Since then, I’ve enjoyed a number of opportunities to image the Moon with the Clark telescope and far better digital equipment, including a Canon 50 DSLR and just recently an ASI-120 webcam. Fortunately, chromatic aberration is not a significant issue with lunar imaging, provided one shoots in monochrome or black and white. For a telescope with such a large aperture and focal length, atmospheric steadiness, or seeing, is far more critical. This is particularly important since the Clark is always in high demand, and access to it must be scheduled well in advance with no guarantees about weather or seeing conditions. Still, I have been fortunate to have occasionally experienced seeing conditions most amateurs would rate 7 to 8 out of 10 — fair to good, but not excellent.

I take pride in sharing a few examples of modern images taken through the great Clark refractor. They include a wide-angle mosaic of the Catharina, Cyrillus, and Theophilus crater trio on the Moon, taken with the DSLR at prime focus under good seeing. The mosaic was compiled from a stack of 50 exposures combined in RegiStax 6. The smallest craterlets resolved are about 1.25 miles (2 kilometers) in diameter.

Capturing fresh images with a storied old instrument, linked to several of the great discoveries about the universe, is thrilling. If you haven’t visited Lowell Observatory, do so. You’ll find history and current science — in areas of solar system, galactic, and extragalactic — seeping from the place. It’s an amazing blend of past and present.