Key Takeaways:

Voyager 2 flew past Uranus on January 24, 1986, more than four years after the probe visited Saturn. Following the excitement at that ringed world (and Jupiter before it), scientists were eager to see what Voyager would reveal at the more distant and enigmatic uranian system.

Suzy Dodd, the project manager for Voyager’s interstellar mission, worked on the sequencing teams for Uranus and Neptune. The group determined exactly when Voyager’s instruments should take data in order to return the information the science team wanted. This meant understanding in minute detail how the planets and their moons moved. The sequencing team orchestrated the various instruments to use every second of the precious flyby windows to image the most valuable targets: the limb or edge of the planets, the terminators where day and night meet, the moons in their orbits, and the planets’ own broad faces.

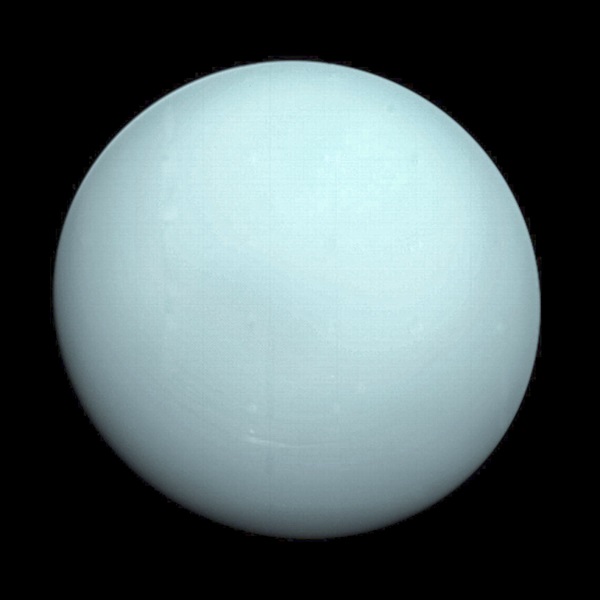

After the rich and complex atmospheres of Jupiter and Saturn, Uranus seemed pretty bland, Dodd recalls. “You didn’t get all the great storms you got at the other planets,” she says. Instead, Uranus “looked like a fuzzy, blue tennis ball.”

Voyager did reveal a previously undetected magnetic field around Uranus, comparable in strength to Earth’s. Due to its nearly 90° axial tilt, Uranus rolls around its orbit like a ball. And while Earth’s orbital and magnetic fields are offset by roughly 12°, Uranus’ are 60° apart. This results in a corkscrewing magnetic field trailing millions of miles behind the planet.

What’s more, scientists still aren’t sure why the magnetic field exists at all, since Uranus lacks the standard liquid metallic inner layer that powers such fields on other planets. Voyager also revealed intense radiation belts around the planet, similar to those seen at Saturn.

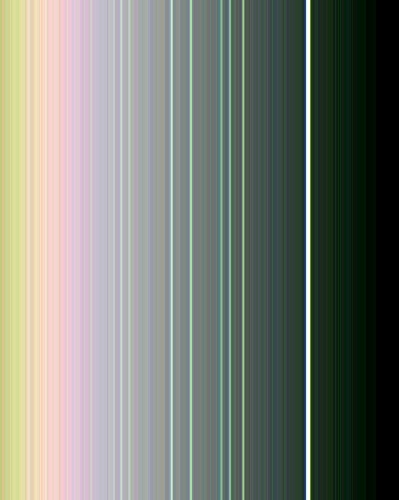

Astronomers at Cornell University discovered Uranus’ ring system in early 1977, just before Voyager’s launch. The sighting was a happy accident, when a chance alignment carried Uranus in front of a distant star. Scientists had planned to use the occultation to study Uranus’ atmosphere, but the star’s repeated appearance and disappearance before it slid out of view behind the planet made astronomers realize that a series of rings surrounded our far-off neighbor. The flyby was a chance to investigate them up close.

Voyager imaged the ring system for the first time, informing astronomers of its detailed structure. The spacecraft also discovered two entirely new rings. The close-up views confirmed that Uranus’ subtle bands are not like Saturn’s bright icy rings; they are dark and reflect little light, making them difficult to see. Scientists think the rings are probably made mostly of ice, like Saturn’s, but covered in organic material such as methane, and then baked dark by the planet’s radiation belts.

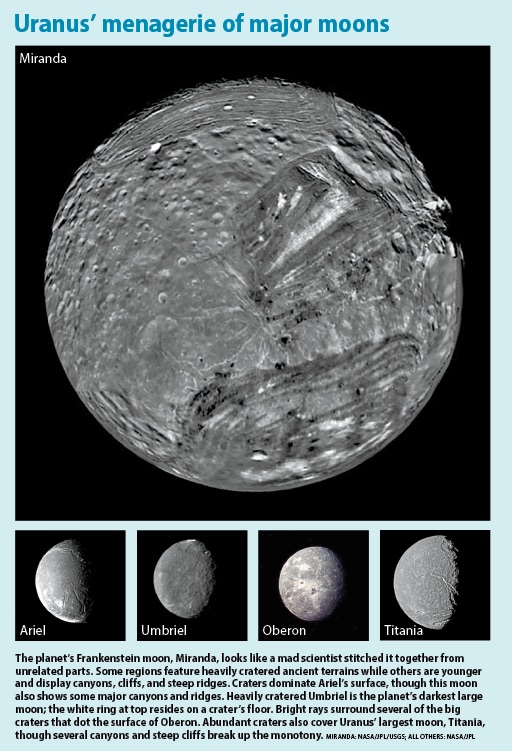

Uranus’ moons, too, camouflage well against the dark of space. When Voyager left Earth, astronomers knew of only five satellites around the planet. From observations during its brief visit, the spacecraft tripled that number, yielding 10 new moons.

“I really think the satellites were the highlight of Uranus,” says Dodd. Voyager images lent the five larger known moons detail and character, telling varied stories of violent pasts.

Two of the new moons, Cordelia and Ophelia, were identified as shepherd moons. They orbit on either side of Uranus’ outer Epsilon ring, and their gravitational pull herds the small particles in that ring along their orbital path and keeps them from dissipating into space. Uranus’ rings are uncommonly narrow; without shepherd moons, the small particles would disperse over long timescales.

Last year, astronomers from the University of Idaho revisited the Voyager data. Thirty years after the flyby, they found evidence for two more tiny moonlets shaping Uranus’ rings. “Nobody — or not many people — had looked at this in a very long time,” says Robert Chancia, who led the investigation. In fact, the Voyager data were taken before he was born. Chancia and his adviser, Matthew Hedman, usually study Saturn’s rings. But recent discoveries by the Cassini spacecraft have added greatly to astronomers’ understanding of planetary rings. So Chancia and Hedman decided to take another look at the Voyager findings, applying new theories to old data.

“There are several narrow ringlets within the rings of Saturn” that provide reasonable proxies for Uranus’ system, Chancia explains. So he and Hedman adopted techniques that planetary scientist Mark Showalter used to find the moonlet Pan in Voyager 2’s observations of Saturn’s ring system.

They found distinct patterns in Uranus’ rings consistent with “wakes” carved by moonlets circling a planet within a ring system. The predicted moonlets are tiny, only 2 to 9 miles (4 to 14 kilometers) across. And they are likely dark, like the rest of the moons and ring system. Confirming the moonlets will be a challenge. But even 30 years later, Voyager is still helping to crack Uranus’ secrets.

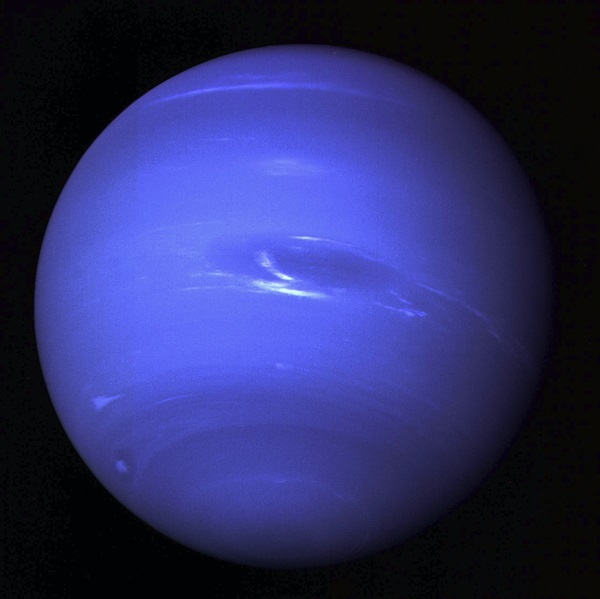

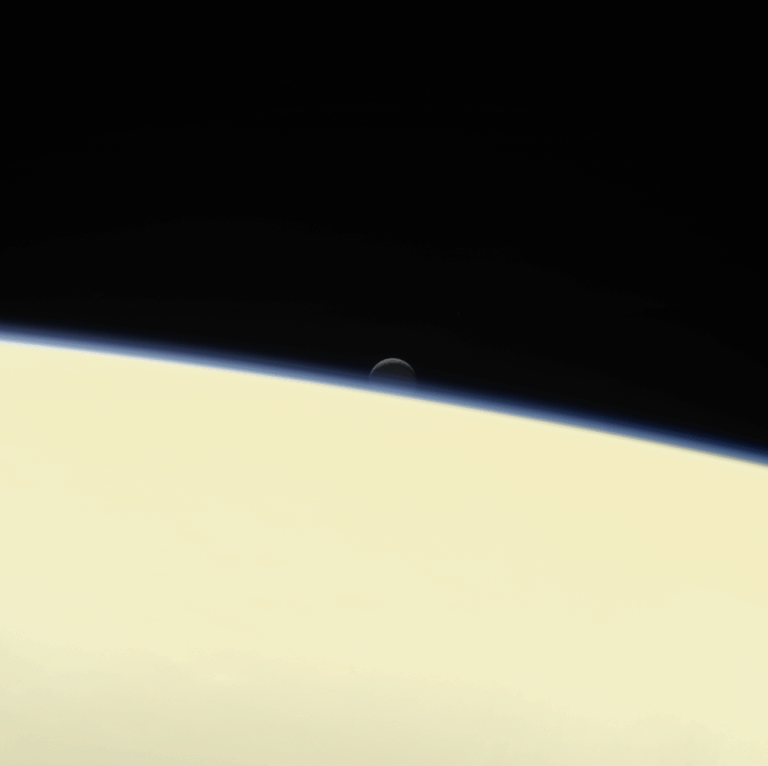

Voyager’s last planetary encounter came August 24, 1989. Far from Uranus’ “fuzzy tennis ball,” Neptune was alive with storms and bright, quick-moving clouds, delighting unsuspecting astronomers. Clouds not only appeared clearly in Voyager images, but they also cast shadows on deeper cloud layers, allowing scientists to measure the planet’s atmosphere in great detail. The “Great Dark Spot,” as astronomers termed the largest tempest, was as big as Earth, swirling in Neptune’s southern hemisphere and boasting wind speeds as high as 750 mph (1,200 km/h). In the decades since, that storm has died, while new storms have risen in its place.

“That was a bit of a surprise to me when you consider the Great Red Spot on Jupiter has been going on for 400 years,” Dodd says.

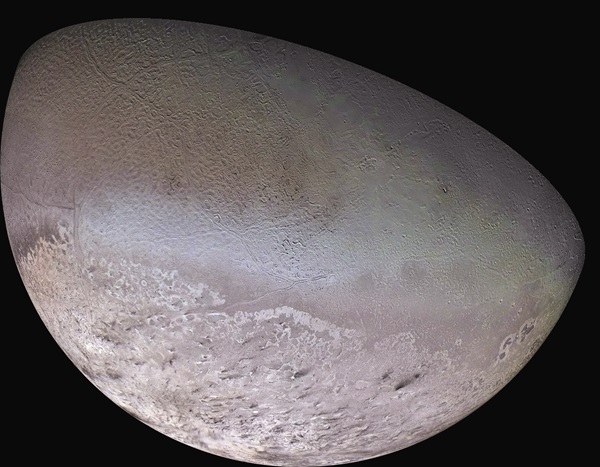

More surprises waited on Triton, Neptune’s biggest moon. Triton was already a hotbed of intrigue; it’s by far the solar system’s largest retrograde satellite, meaning it orbits in the direction opposite to its planet’s rotation. This is usually a sign of a captured object, but most other retrograde moons are small, misshapen asteroids. Triton is three-quarters the size of our Moon, and survived its capture intact. Scientists wanted close-up views of the satellite, and since it was the last target, they were free to adjust Voyager’s trajectory as needed. So the spacecraft swooped only 3,075 miles (4,950km) above Neptune’s north pole — its closest approach to any object during the mission — and flew toward its encounter with Triton.

The last world Voyager 2 visited stunned scientists. The moon boasted a thin atmosphere, polar caps, and active geysers that spewed icy material miles high. The active cryovolcanism puts Triton in a select group of satellites, in the company of other dynamic moons such as Europa and Enceladus.

Voyager also discovered six new moons orbiting Neptune and delivered clear pictures of its ring system for the first time, revealing the rings to be clumpy but complete, unlike those at Uranus.

And as it did at Uranus, Voyager discovered that Neptune’s magnetic pole is misaligned from its rotational pole, causing extreme variations in its magnetic field as the planet rotates. Furthermore, both planets’ magnetospheres are offset from center by a large fraction: about one-third the planet’s radius for Uranus, and nearly half a radius for Neptune. Both planets could have oceans of conductive icy slush that perform the work of the liquid metallic cores at Earth and Jupiter, but inconclusive models and observations have left scientists with little more than guesswork as to what exactly drives the magnetic fields that Voyager observed.

Voyager also detected aurorae on Neptune. Due to the strange and complex nature of the planet’s magnetic field, these aurorae don’t occur only at the poles; instead they are scattered across Neptune’s upper atmosphere.

Voyager also closed a contentious chapter in astronomy history by revising Neptune’s mass downward by around half a percent — or roughly the mass of Mars. This miscalculation had sent astronomers on a wild goose chase through the years as they tried to make sense of Uranus’ and Neptune’s orbits, usually by invoking the existence of a mysterious Planet X tugging on both of them. (Pluto was found as a direct result of this hunt, but its small size was never enough to resolve the initial problem.) Voyager settled the issue, as Neptune’s smaller mass means it and Uranus orbit just as they should.

To mark the final flyby, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory hosted a special event celebrating Voyager’s journey and accomplishments. Scientists shared images with the public, and rock-’n’-roll legend Chuck Berry, whose music lives on as part of Voyager’s Golden Record, played in a special concert.

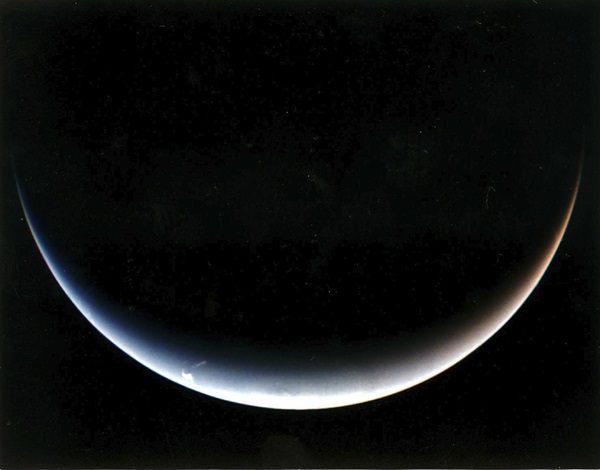

At the edge of our planetary system, 2.75 billion miles (4.43 billion km) from Earth, Voyager turned its cameras back for a last look, imaging farewell shots of a crescent Neptune. Dodd recalls her reaction to the images: “Wow. The planetary mission is done. We’re going off into the deep dark and cold realms of space. Who knows how long the mission will last?”

Epilogue

When she left her position with the Neptune team, Dodd says, no one then imagined Voyager would continue as long as it has. She returned to Voyager’s interstellar mission in 2010, 21 years after she left the project. In many ways, she admits that the spacecraft is an artifact — memory and power limited, with many of its specialists long since retired or passed on. Since Voyager’s departure from Neptune, many of its instruments have gone quiet. There is no need for imaging cameras in the dark void of space. But that does not mean the project is defunct.

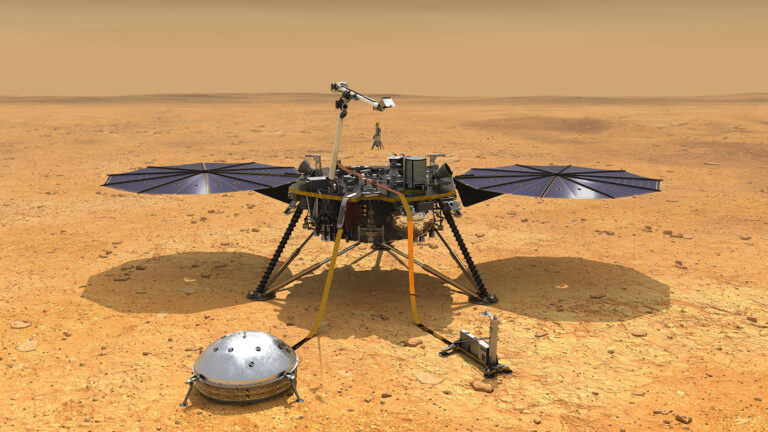

Voyager continues to measure magnetic fields, charged particles, plasma density, and more as it cruises the solar system’s hinterlands, teaching scientists about the subtle edges of the solar system’s boundaries. Voyager 1 has passed beyond the reach of the solar wind, and thus is sampling aspects of interstellar space, though it still lies well within the Sun’s gravitational influence. Voyager 2, following a slower trajectory from its two-planet detour, tags behind, still sampling the solar wind. From their distance, it takes more than 15 hours for their signals to reach Earth.

Sometime in the next decade, the spacecraft will lose power and begin to shut down. Dodd’s team will turn the Voyagers’ heaters off first, and one by one, the science instruments will succumb to the cold of space. But the spacecraft themselves and their Golden Records will journey on, carrying humanity’s imprint into the cosmos.

It will be years before any spacecraft retreads Voyager’s path to Uranus or Neptune. With at least half a century of technological advances behind it, any future craft will undoubtedly revolutionize our understanding of the ice giants all over again. But it’s safe to say that nothing will match Voyager for sheer adventure and scope. Decades after its primary mission, Voyager continues to teach, to inspire, and to explore.