Key Takeaways:

- Voyager 2's 1989 flyby of Triton revealed a geologically young surface with plumes, initially attributed to solar heating, but now potentially indicating a subsurface ocean.

- The presence of a subsurface ocean on Triton is supported by its "cantaloupe terrain," attributed to diapirs, and the re-evaluation of the plumes in light of discoveries on Europa and Enceladus.

- Tidal heating from Triton's orbital tilt, rather than gravitational interactions with Neptune, is hypothesized as the mechanism maintaining a potential subsurface ocean.

- The proposed Trident mission aims to determine Triton's ocean status through a flyby, utilizing a magnetometer, while a future orbiter mission is considered necessary for a comprehensive exploration of the Neptune system.

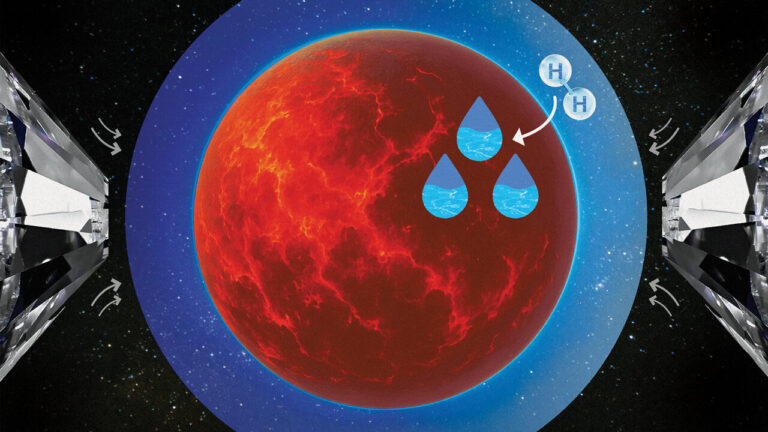

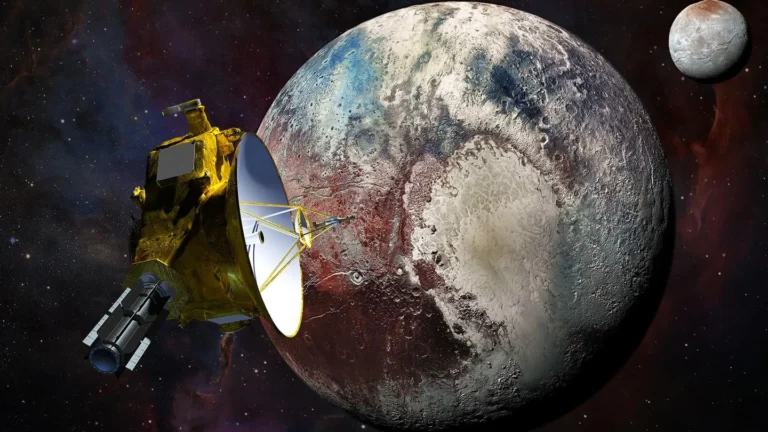

When VOYAGER 2 flew by neptune and its largest satellite, Triton, in 1989, it revealed a moon with never-before-seen terrain and plumes spurting from the surface. At the time, scientists attributed the plumes to heating from the Sun. But recent advances in understanding ocean worlds such as Jupiter’s moon Europa and Saturn’s moon Enceladus have raised the possibility that Triton’s plumes may indicate it, too, harbors an ocean under its icy crust — a place where life may have managed to evolve.

“These are not just solid rock-and-ice bodies in the outer solar system,” says Kathy Mandt, a planetary scientist at Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory. “The subsurface liquid water could have the potential for hosting life based on what we see in the depths of our own oceans.”

Longtime Triton researcher Candice Hansen of the Planetary Science Institute in Arizona agrees that ocean worlds may be key sites for life to evolve. “On Earth, if you have liquid water, you’ve got life,” she says. Several years ago, at a meeting of planetary scientists, she recalls that many of the Earth-focused oceanographers present were confident that an extraterrestrial ocean would lead to the discovery of life. “They [said], ‘You’ll find life, we’ll find it all over,’ ” Hansen says.

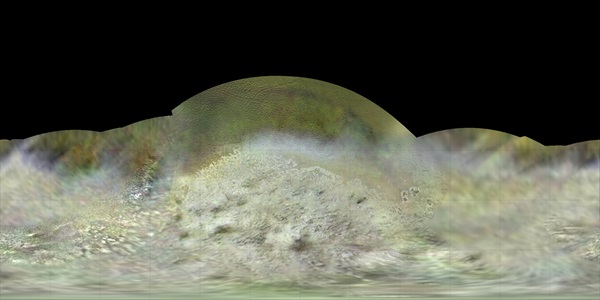

Voyager glimpsed Triton only briefly, but that glimpse was tantalizing enough. The spacecraft revealed that the moon’s surface is young, with some estimates setting its age as low as 10 million years. The reshaping and repaving of the terrain suggest that something is happening beneath the surface. Whether that process comes from the movement of rocks or the effect of an ocean remains unclear.

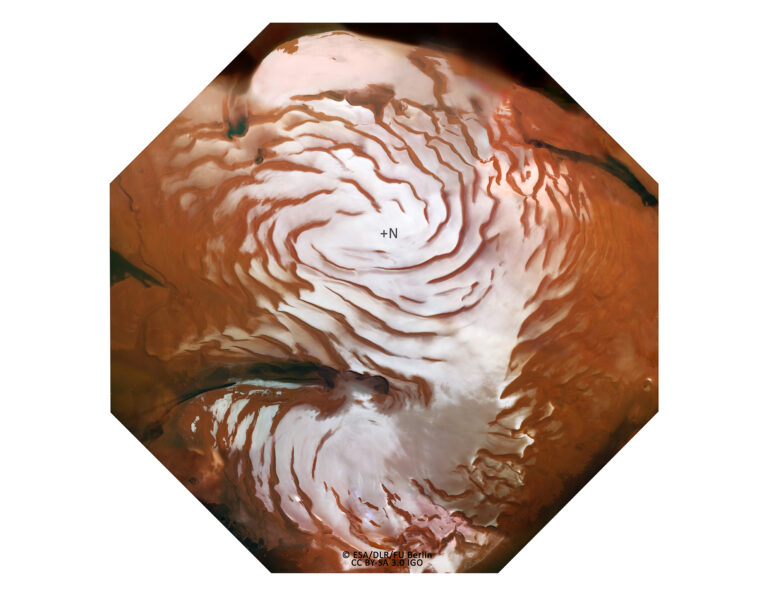

One of the moon’s most intriguing features is its cantaloupe terrain — rugged surface features that resemble the skin of the fruit whose name it bears. Planetary scientists think that rising blobs of ice, known as diapirs, cause this terrain as they are pushed upward through the more brittle surface by heating from below.

Voyager also glimpsed plumes of material shooting a few miles above the surface. “At the time, we developed a whole theory about solar-driven nitrogen geysers,” says Hansen, who was on the Voyager team. She describes some of the reasoning as circumstantial, because the geysers appeared where the Sun was nearly directly overhead. As sunlight heated the ices, nitrogen could have jumped from solid to gas to become the plumes.

With the discovery of geysers spouting water from Enceladus and Europa, scientists are taking another look at Triton’s plumes. “Maybe Triton is like Enceladus and Europa, and there could actually be water plumes coming from an interior ocean,” says Mandt.

Material from the plumes has recolored Triton’s surface: Voyager spotted streaks suggesting material fell from previously or currently active geysers. If the geysers draw water from a liquid ocean, samples of the interior may lie on the moon’s surface, ripe for the taking.

Together, these studies suggest the possibility that Triton may be hiding liquid beneath its surface, making it a potentially habitable site in the solar system. “We’ve got some tantalizing clues that it is an ocean world,” says Amanda Hendrix, also of the Planetary Science Institute.

Triton was born in the Kuiper Belt, the ring of icy rocks orbiting the Sun beyond the planets. Early in their lifetimes, Neptune and Uranus likely engaged in an intricate dance that moved them, and the Kuiper Belt, to their present locations. This cosmic shuffle also allowed Neptune to capture at least one Kuiper Belt object as a moon: Triton.

Triton’s surface probably felt the first tremors of activity during that violent grab. Tidal heating caused by energy dissipation during its capture and the slow circularization of its orbit likely caused geologic activity on the surface. Ices may have moved or melted, and its interior structure may have been briefly affected.

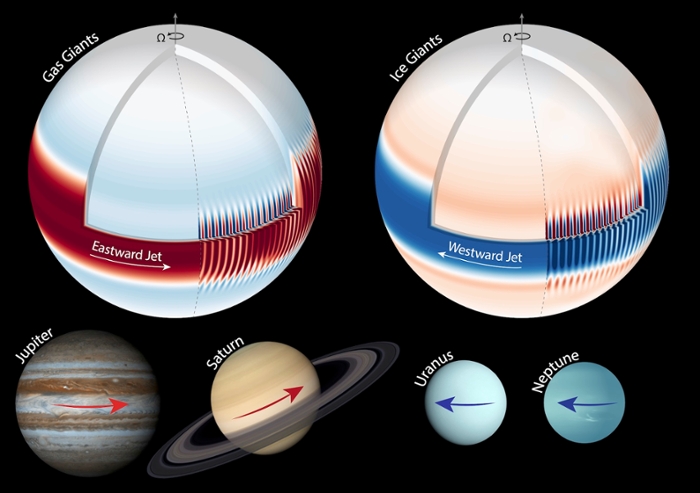

But that one event billions of years ago isn’t enough to keep Triton’s surface fresh. Something else must be warming its interior today to create a liquid ocean. On Europa, the varying gravitational tug from Jupiter and its fellow moons may be helping to maintain an ocean, but Triton is Neptune’s only large moon.

Instead, it’s Triton’s orbital tilt that may enable a liquid ocean. Although the moon always keeps the same face toward its planet, its orbit ducks above and below Neptune’s equator, allowing its poles to experience a change in seasons. As the moon orbits the ice giant, its tilt means that different parts of its interior are kneaded by the planet’s gravity. That could be enough to keep a liquid ocean from freezing solid, Hansen says.

Earlier this year, the NASA Outer Planets Assessment Group’s Roadmaps to Ocean Worlds (ROW) team named Triton the highest priority of the candidate ocean moons. Before researchers can establish Triton as a potentially habitable site in the solar system, they need to determine whether it actually boasts an ocean. “The question about Triton is not so much about its habitability as whether or not it’s an ocean world,” Hendrix says.

That means sending a mission to the moon. Mandt and Hansen are both part of the Trident mission, whose main goal is to determine whether or not Triton is a water world. Trident would make a single flyby of the moon, lowering its cost to make it eligible for funding as a NASA Discovery-class mission. A magnetometer similar to the one that helped confirm the presence of an ocean on Enceladus should help to answer the important question of whether Triton also has a subsurface ocean. Along the way, Trident would also take images of the surface. The mission is currently in the proposal stage.

Trident’s flyby may answer some questions, but an orbiter would answer many more. “I think the whole Neptune system deserves a Cassini-like mission,” Hendrix says, referring to NASA’s iconic 13-year mission exploring the Saturn system.

That may not be completely out of line. A Uranus mission was one of the highest priorities for the 2011 Visions and Voyages Decadal Survey, which outlined top scientific goals for the 10-year period between 2013 and 2022. However, the ROW study pointed out that traveling to Neptune would satisfy the requirements of studying an ice giant while also covering Triton.

“We need to go back with a mission that can really map out the compositions of these different terrains,” Hansen says, adding that the composition can tell a great deal about the origins.

Understanding whether Triton has an ocean is key to understanding not only the potential habitability of the small moon, but also establishing the way life may evolve elsewhere in the solar system. Europa and Enceladus, whose subsurface oceans are known to exist, are clearly a high priority. But Hansen is confident that the discoveries made at those sites will affect studies of Triton.

“If we find life at Enceladus, we’re going to say, ‘Do you think life could be at Europa? How unique is Enceladus?’ ” Hansen says. “If we don’t find it, we’ll want to know if it’s just Enceladus [that is barren] or is there no life anywhere — let’s test Europa. Either way, you’re going to go to the other one.”

If neither Enceladus nor Europa hosts life, then researchers will want to find other sites where life could have evolved. And even if both worlds are rich in alien life, a study of Triton could increase understanding of the various paths life does — or does not — travel to evolve. “No matter what the outcome is, you want to go to Triton,” Hansen says.

For Hendrix, the call to explore Triton is one of diversity. Currently, the Europa Clipper mission is preparing to send an orbiter to Europa to investigate the moon, and there is also talk of a subsequent lander mission. But Hendrix is wary of focusing too much on a single target. “Let’s spread out our resources a bit more evenly so we can assess the habitability at one moon while assessing whether there’s an ocean world at another,” she says. “In that way, we can be understanding the whole spectrum of ocean worlds in our solar system a little better.”