Our solar system shimmers with a host of volcanoes. Its erupting menagerie includes forms familiar to us, like the cinder cones and graceful shields of the martian landscape. The mountains of Venus take on more alien shapes, given the planet’s dense atmosphere and unique rock chemistry: pancake domes, spiderwebs, and ticks. Farther out, the volcanoes on Jupiter’s moon Io display violent natures, blasting material hundreds of miles above the moon’s pizzalike face.

Some volcanoes, called cryovolcanoes, even spew icy slush instead of rock: The ice worlds Europa and Enceladus have their own versions of Vesuvius, sending jets of freezing water into the void. At Neptune, the moon Triton flaunts unique eruptions, with chilled nitrogen columns wafting into dark skies. We even see hints of cryovolcanism at Pluto’s crater-topped Wright and Piccard Mons.

We thought we’d seen it all. Then came Ceres.

One of a kind

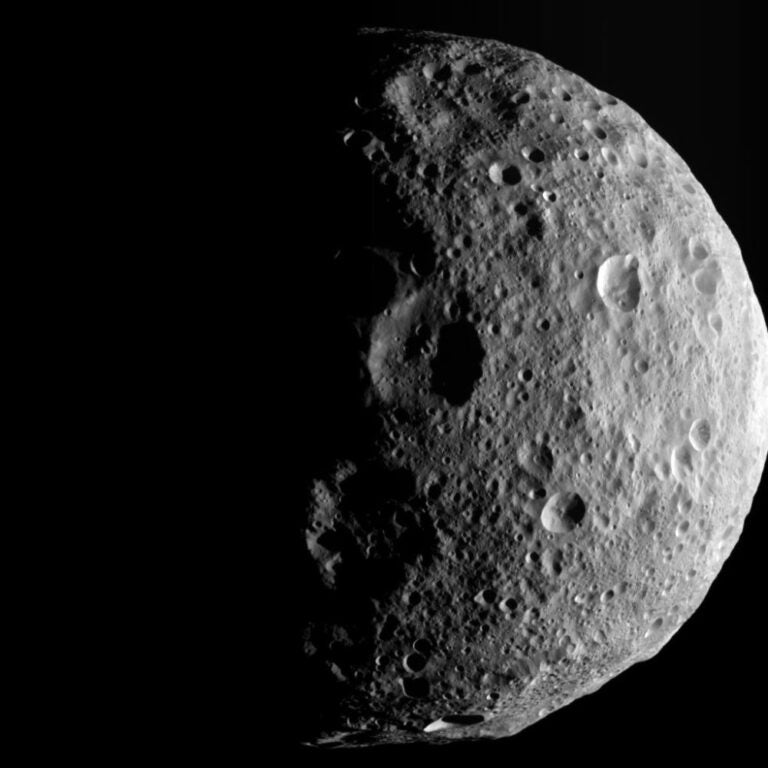

Ceres is part of the main asteroid belt, a doughnut-shaped band of rocks circling the Sun between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. As the largest member, Ceres is roughly spherical: It’s 588 miles (945 kilometers) across and constitutes nearly one-third of the mass of the entire belt. It was the first dwarf planet — and the first object in the main belt — ever discovered. However, when Giuseppe Piazzi first spotted it in 1801, the object appeared merely as a point of light, similar to a star. Hence, Ceres and its main-belt siblings were given the name “asteroids,” from the Greek word for “starlike.”

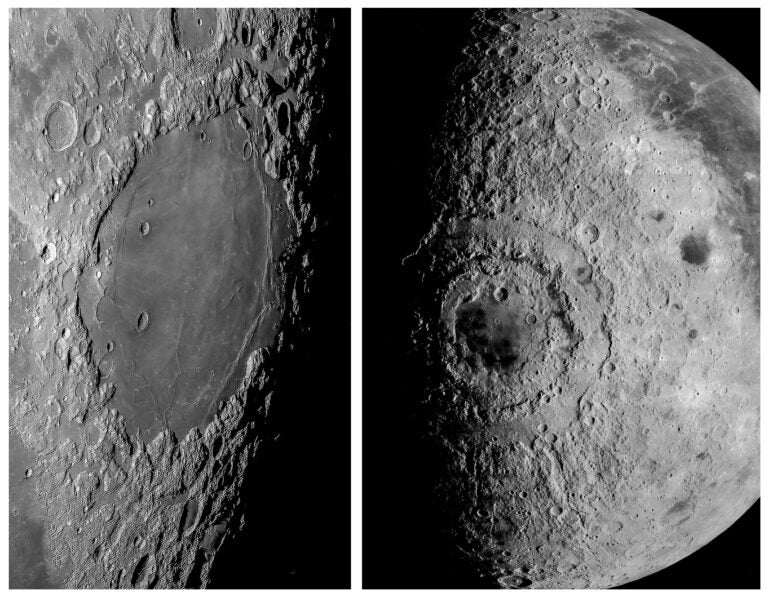

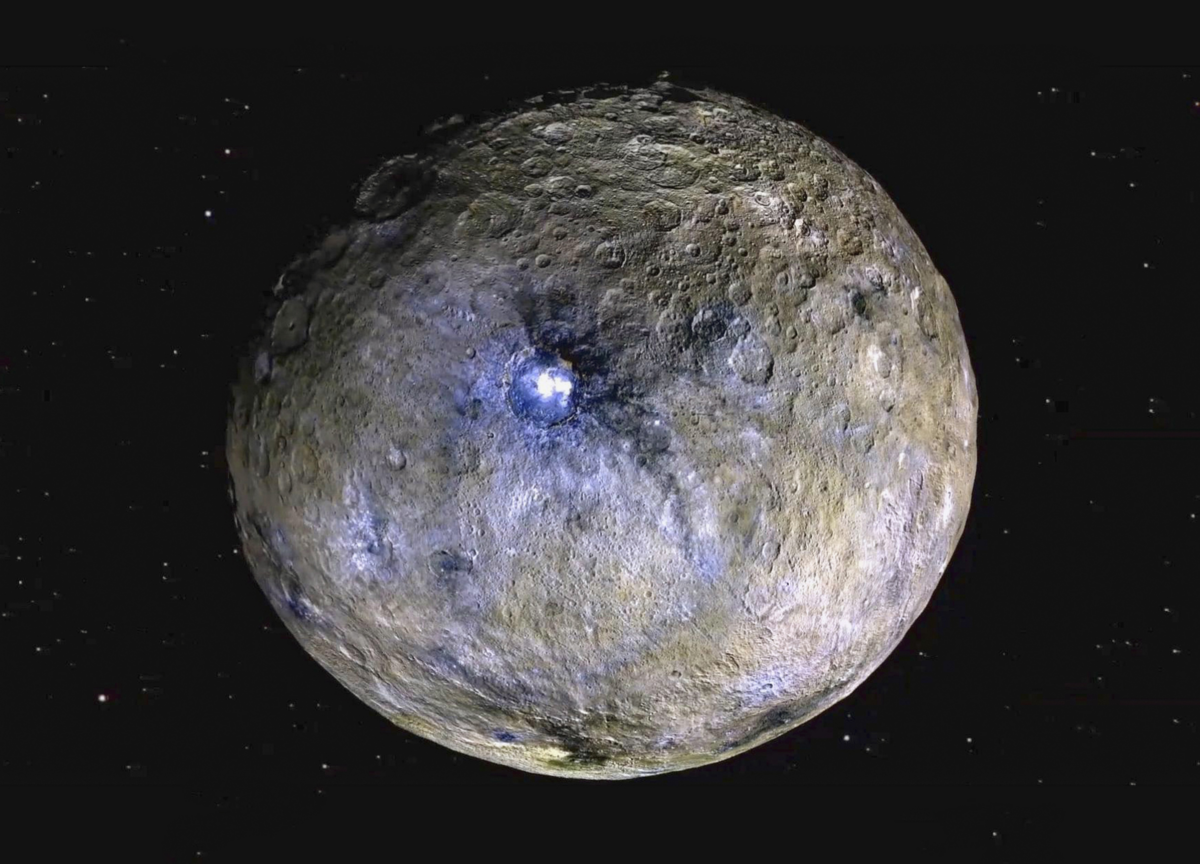

Although closer than any other dwarf planet or icy moon, Ceres is too small to study for all but the most advanced telescopes, and even those instruments resolve its face as a handful of pixels. Earth-based observations showed hints of water in its spectrum and noted a mysterious white spot on one hemisphere, which astronomers guessed might be an outcropping of water ice. Some researchers speculated that Ceres was a rocky ball with hidden ice deposits. Others theorized that the dwarf world was covered with a smooth, young surface — perhaps a Europa-like cue ball hiding an ocean beneath a dust-spattered skating-rink crust.

In fact, a visiting spacecraft revealed that Ceres is none of these, but instead encrusted with the chemistry of ancient seas, with salty mineral deposits scattered across its face. Although Ceres is a rocky body, it holds between 20 and 30 percent water, the majority of which is probably frozen. The icy dwarf is an in-between world, inhabiting a twilight zone between terrestrial, rocky planets and the water-ice globes of the Sun’s outer realm.

Dawn at Ceres

Much of what we know about Ceres comes from NASA’s Dawn mission, which arrived at the icy world in spring 2015. Dawn first settled into a high, slow, mapping orbit. As the mission progressed, flight engineers commanded the craft to spiral closer.

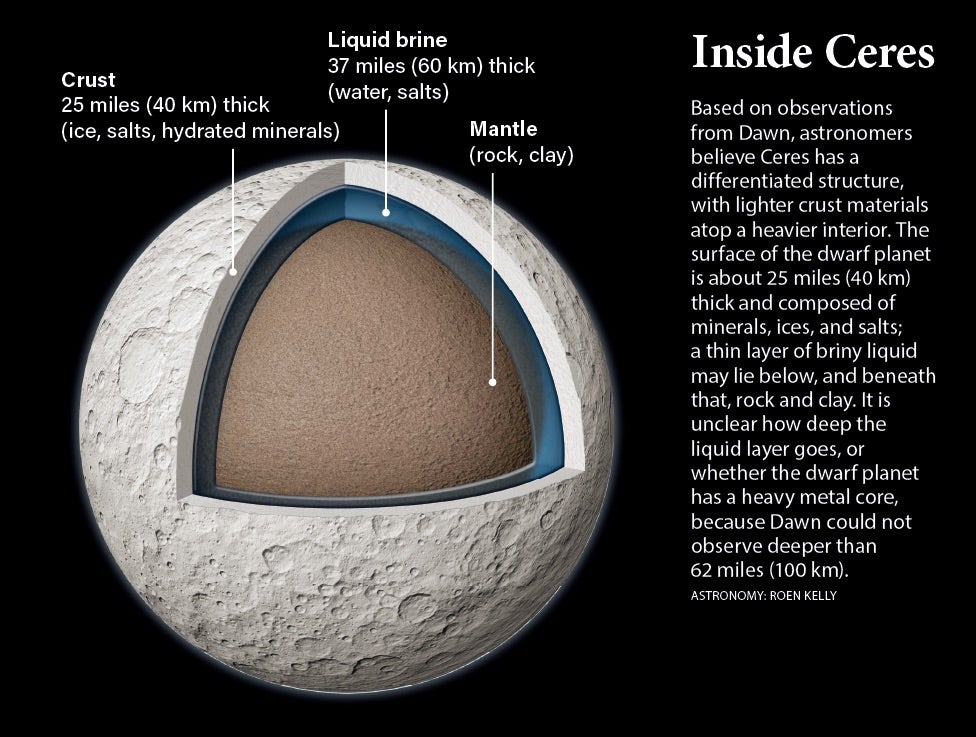

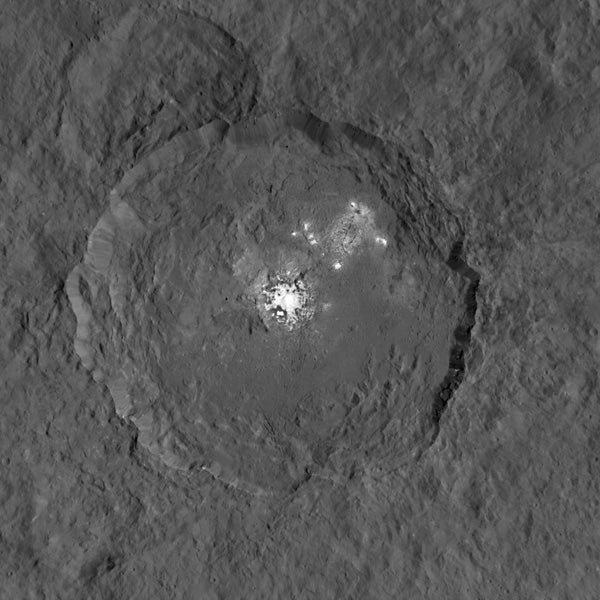

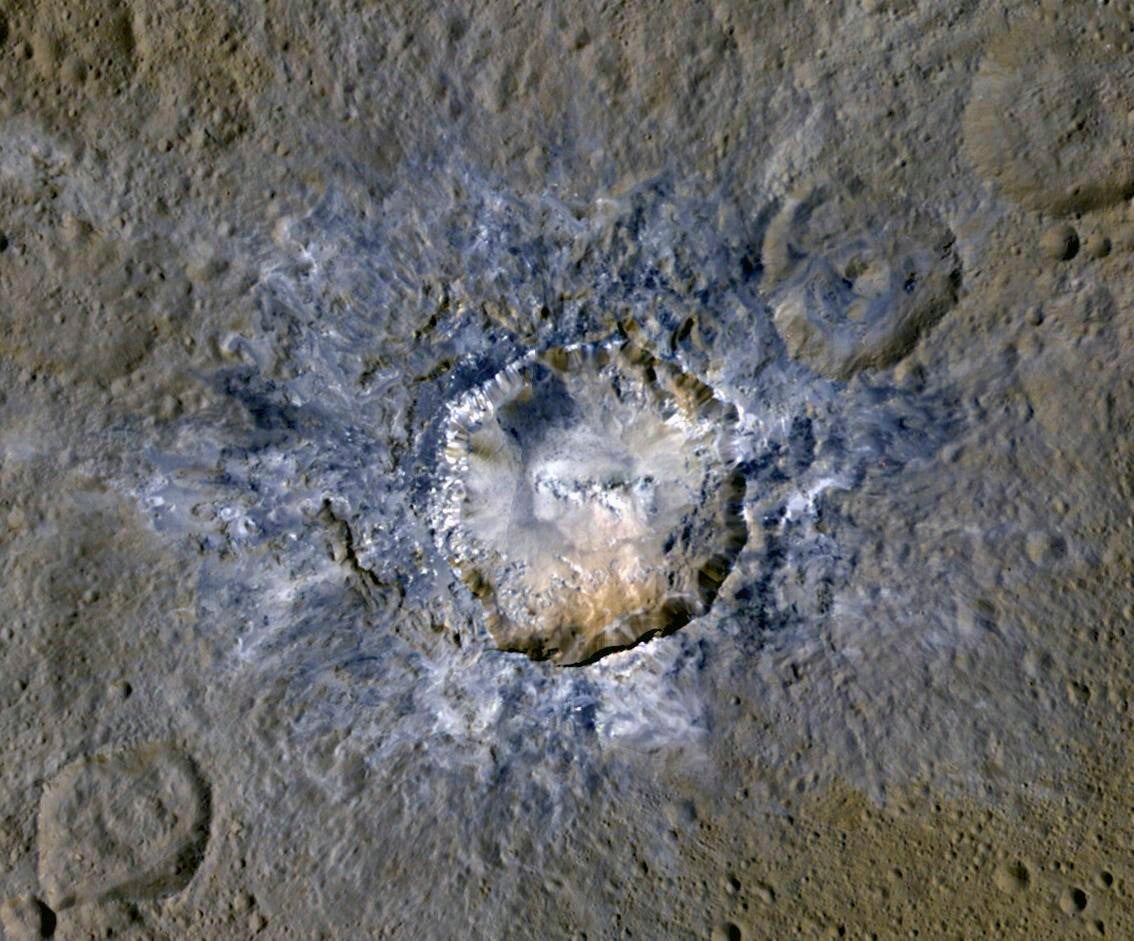

Like the traditional planets, Ceres is differentiated: Heavier rock and metal settled into a core while lighter ices and rock rose to the mantle and crust. Today, the dwarf planet’s surface is a mix of rock, water ice, and hydrated minerals such as clay and carbonates (salts). Most of Ceres is as dark as asphalt, but its spots range from a dull gray (akin to driveway concrete) to the glaring luster of the sea ice at Earth’s poles. In all, Dawn charted some 300 bright spots similar to the largest one seen from Earth.

Although astronomers originally speculated that the dazzling areas were icy outcroppings, Dawn revealed the blemishes instead consisted of hydrated magnesium sulfate, similar to Epsom salts, and sodium carbonate, which is typically left behind as seasonal terrestrial lakes evaporate. The salts within Ceres’ bright regions make it one of only three worlds whose surfaces are known to contain carbonates, which are considered markers for habitable conditions; the other two carbonate-rich worlds are Earth and Mars.

Ceres’ briny regions prove that water still exists near the surface: The majority of spots are associated with craters, so they may be the result of impacts that freed subsurface water. Exposed liquid would sublimate (change directly from liquid to vapor) into space. Ceres’ spots may also point to a primordial ocean that existed for some time beneath its dusty surface. Gravity studies show that a thin sea — perhaps a mixture of water and mud — may exist under the crust even today.

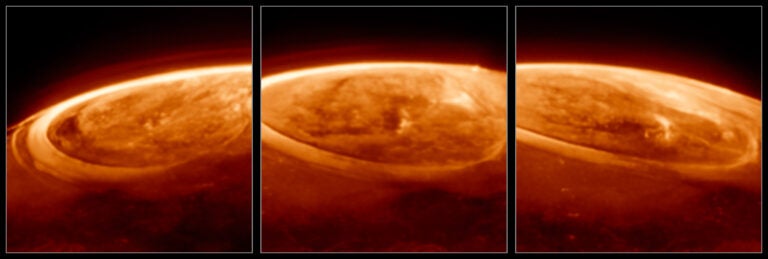

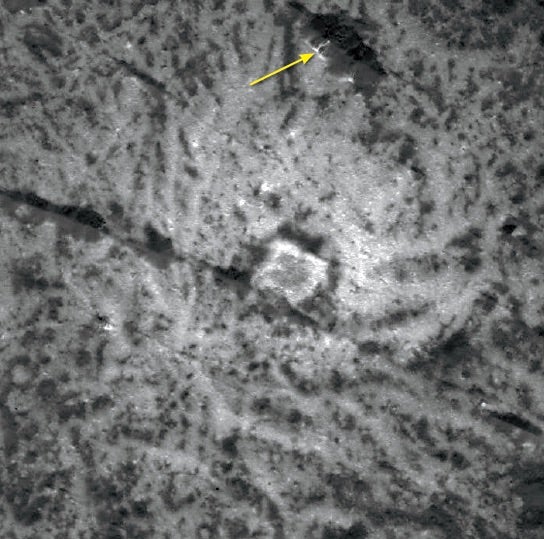

Dawn detected expanding patches of ice on the walls or floors of several craters attributed to a seasonal ice cycle. Astronomers watched one such cycle in Juling Crater, located in the southern hemisphere. According to Dawn’s chief engineer and project manager, Marc Rayman, “In southern hemisphere summer there is greater heating on the floor of that crater, so that warms the ground and releases water vapor. The vapor comes up and condenses on the cold north wall.” Researchers charted one area of ice that grew by hundreds of acres: “It’s water molecules being transported from one location to another,” Rayman says.

Ice has been observed all across Ceres. But Ceres is too close to the Sun for ice to remain stable on the surface. So, when ice is observed, it’s a strong indication of some kind of activity. “Ceres is clearly a geologically active world,” Rayman says.

A leaky world?

Geysers are one mode of transporting salts or condensing water from Ceres’ interior to its surface. The brilliant deposits may represent sites of ancient cryovolcanism, where water vapor leaked or exploded through the crust, forcing out material from subsurface aquifers or seas.

Some activity may continue even now. In 2014, the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Herschel Space Observatory detected clouds of vapor escaping from two distinct spots on Ceres at a rate of 13 pounds (6 kilograms) per second. This observation was the first confirmation of water plumes in the asteroid belt. Scientists theorized the vapor came from ice sublimating on the dwarf planet’s surface.

But the Herschel observations are quite difficult to interpret. Revised assessments have called the results into question. For its part, Dawn did not see enough surface ice to account for what Herschel detected. But if there is subsurface ice, some of it could be a source of water that makes its way up through the ground.

Another possibility is that increased solar activity produced the transient water vapor that Hershel detected. “Say the Sun produces a coronal mass ejection, so a large number of energetic solar particles impinge on the surface and themselves liberate water molecules,” Rayman says. Dawn carried an instrument to detect such high-energy particles from the Sun to investigate this possibility. Astronomers set up a coordinated international campaign between Earth-based telescopes and Dawn, but solar activity was simply too low to demonstrate whether the Sun’s activity freed water from the surface.

The search continues. “It’s a hard problem because Dawn wasn’t made to study that sort of thing,” Rayman says. Not only was Herschel’s detection a tentative one, but astronomers aren’t sure how such a haze could stick around without an atmosphere to hold water in. In 2016, Dawn changed its orbit to search for any indication of water vapor. It examined Juling Crater’s ice and looked at Occator Crater when it was on the dwarf planet’s limb, but failed to find evidence of water vapor. Researchers later directed the spacecraft to take a second look, but again were left with no results.

One lonely mountain

Nevertheless, the picture we are left with is a rocky world with a wet subsurface that periodically seeps or explodes into space in clouds and plumes. If this is the case, Ceres should be peppered with cryovolcanic features. But Dawn’s initial survey of the dwarf planet revealed only one large mountain, christened Ahuna Mons.

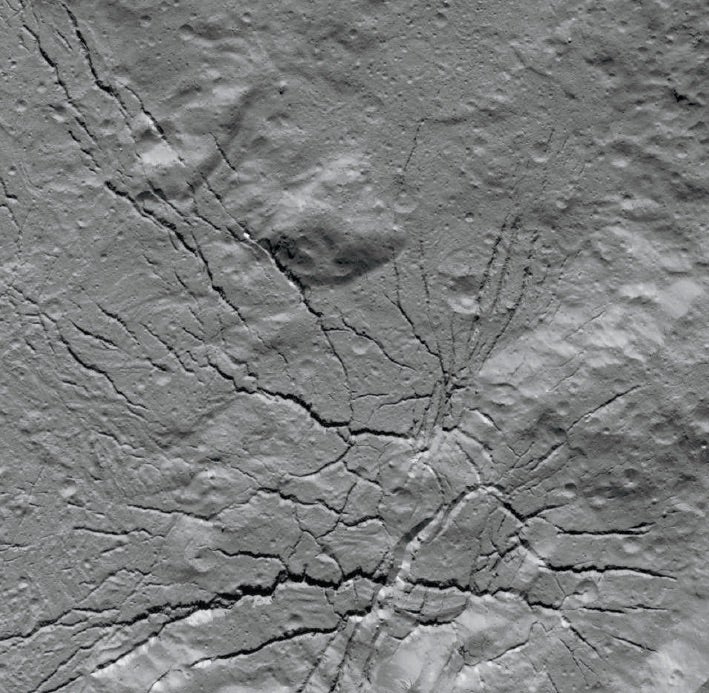

Ahuna Mons is a strange feature. It rises sharply from the cratered landscape, towering some 3 miles (5 km) on its steepest side. Pointing to a combination of characteristics, researchers are convinced that Ahuna Mons is volcanic. Its summit is cracked like those of volcanic domes seen on other worlds, such as Mars, Venus, and Earth. The mountain’s flanks appear to have been scored by rockfalls. Volcanic domes on terrestrial planets tend to form a brittle shell at the summit, which fractures and produces similar debris trails on their flanks.

Everything about Ahuna Mons indicates that the mountain is geologically young. Ceres has no atmosphere to protect it from meteor impacts, so much of its surface is weathered by the constant drizzle of micrometeorites, resulting in rounded hills and valleys. But Ahuna Mons shows sharp definition with few craters, suggesting it hasn’t experienced as much weathering. A final clue to its youth is its color: Ice and rock surfaces tend to darken over time thanks to constant solar radiation, but the dome is one of the brightest regions on Ceres.

Researchers estimate the age of the summit to be between 70 million and 240 million years old. The massif may have risen quite quickly, building to its current altitude of 13,000 feet (3,965 m) in just a few hundred to a few hundred thousand years. The idea that it might have reached that height so quickly inspires scientists like Rayman. “Even a few hundred thousand years for a structure that’s 13,000 feet high, that’s pretty fast,” he says. “Not only that: The structure is more than 70 million years old, and it’s still standing with impressively steep slopes.”

It is unclear whether Ahuna Mons still erupts cryolavas (most likely thick, muddy water). In light of its potential for geologic activity, researchers began searching Ceres’ surface for other evidence of past volcanism, but the search was difficult. Most of the world’s volcanic activity seems to have occurred hundreds of millions of years ago, and it may stretch back as far as 2 billion years. Time, impacts, radiation, and micrometeorites have nearly erased many of the ancient eruptions’ fingerprints.

But they are there. Researchers have identified at least 21 other cryovolcanic domes ranging from 10 to 53 miles (16 to 86 km) across. To find them, investigators compared computer-modeled domes with Dawn’s stereo images of the surface to reveal candidate sites that have gradually settled and sunk into the cratered landscape over eons. Temperatures on Ceres are not low enough to make ice sufficiently strong to support a massive structure like a mountain. Thus, ridges, canyons, and peaks tend to relax and sink in a process called viscous relaxation. Surface features flow slowly, like a glacier, eventually fading into the neighboring landscape. Researchers played a game of hide-and-seek, searching out rises that fit a model of a tall mountain that had lapsed into its surroundings. “[The candidate sites] are all a kilometer or more in height, and that really stands out on a body like Ceres,” Rayman says.

Data indicate that new eruptions of cryovolcanoes have broken out, on average, every million years over the span of the past billion years. But the rate at which new material is deposited onto the surface is small compared with terrestrial planets — on the order of 100 to 100,000 times less. Each year, the average volume of cryolavas on Ceres is about 13,000 cubic yards (9,940 cubic meters), or enough to fill four Olympic-sized swimming pools. This is tiny compared with Earth’s volcanic activity, which generates 1 billion cubic yards (765 million cubic meters) of molten rock annually. Scientists calculate the flow by comparing some 20 other domes on Ceres, each in various degrees of erosion, to Ahuna. Estimating their ages, researchers then get a rough average rate of cryovolcanic formation over the past billion years.

And what of the future? “Making predictions for Ceres’ future activity is definitely difficult,” says ESA researcher Ottaviano Ruesch, whose areas of interest include geology on Ceres and Dawn’s first target, the main belt asteroid Vesta. “What we can say is only on a speculative basis, but if we consider that cryovolcanism was persistent throughout Ceres’ history until geologically recent times [from a few billions of years ago up to a few hundred million years], there is no reason to exclude events in the upcoming million years.”

Feeding the fires

On the terrestrial planets, the leftover heat of planetary creation can be enhanced by heat produced in their cores when radioactive elements like uranium decay. The larger the planet, the more radioactive material gathered during its formation process; larger planets also retain heat for longer periods. In the case of Earth and possibly Venus — the two largest terrestrials — volcanism is still alive today. Mars’ volcanic era ended roughly 500 million years ago, although ESA’s Mars Express and NASA’s Mars Odyssey orbiters have located several hotspots that may indicate residual low-level activity.

Smaller objects like moons and asteroids did not have as much radioactive material to start with. Yet Ceres’ cryovolcanoes appear young enough that core radioactive heating on its own is not to blame. Something else is afoot.

Voyager revealed that volcanism can be triggered by forces other than radioactive heating. Tidal friction, that gravitational taffy-pull between planets and moons, can generate prodigious amounts of internal heat. But not at Ceres. The lonely world is too far from other objects to be significantly affected by gravitational tugging. Another possibility has to do with what’s in the water. Materials like ammonia, methane, and various salts can lower the melting point of water ice — which any cryolava on Ceres could contain — enabling water to flow and cryovolcanic eruptions to take place even in the chilly temperatures of the asteroid belt. Since Dawn found evidence of carbonates and ammonia-rich clays on the dwarf planet’s surface, its observations hint at a subsurface sea laced with these materials.

The cause of the alien volcanism on Ceres remains a mystery, but the Dawn team has put forth several possibilities. One possible explanation is that a large impactor struck the primordial Ceres after it had differentiated. The impact could have pulled hot rock and radioactive material up from the deep layers of Ceres’ mantle, placing pockets of geologically warm material close to the surface.

Whatever their origin, the bizarre sludge volcanoes of Ceres put the small world in good company with exotic Enceladus, Europa, Pluto, and the other cryovolcanic worlds of our solar system. What we do know is that Ceres challenges our preconceptions of what a volcanic world should look like, and how it should arise. But challenging our preconceptions is one of the great values of science.