Soon after his discovery, astronomers realized that Herschel had discovered the first new planet since antiquity: Uranus. The astronomical community was delighted. With one observation through a 6½-inch reflector, Herschel had doubled the radius of the solar system.

Bringing the universe to your door. We’re excited to announce Astronomy magazine’s new Space and Beyond subscription box – a quarterly adventure, curated with an astronomy-themed collection in every box. Learn More >>.

In 1820, French astronomer Alexis Bouvard compiled position tables for Uranus. He set out to define, from observations made since its discovery, the planet’s orbit. But the orbit he deduced didn’t match either pre-discovery positions of Uranus (when it had been spotted without knowing its true nature) or those made after its discovery. And its deviation from the older ones was striking.

Urbain Jean Joseph Le Verrier, an astronomer at the Paris Observatory, reduced the problem to a single question: “Can the anomaly be explained by the supposed action of a foreign and hitherto unknown body on Uranus?” After lengthy calculations, he sent the presumed object’s position to several observatories. At the Berlin Observatory, Johann Gottfried Galle discovered Neptune on the day he received the letter from Le Verrier — September 23, 1846 — less than 1° from the predicted position.

Uranus, which lies an average of 1.8 billion miles (2.9 billion kilometers) from the Sun, and Neptune, 2.8 billion miles (4.5 billion km) away, are on every amateur astronomer’s “life list.” Just seeing the ice giants through binoculars or a small telescope is a score for beginners. But what can you see if you look carefully and through a medium or large scope? This is the month to find out.

Where to look

Uranus reaches opposition October 28. When an outer planet is at opposition, it lies on the side of Earth opposite the Sun. It rises at sunset, stands highest in the south at midnight (which may be 1 a.m. if Daylight Saving Time is in effect), and sets at sunrise. The planet also is closest to Earth around opposition, so its apparent size is largest. Finally, the Sun is behind us, so the planet’s entire sunlit side is in view. Add these factors together, and you’ll get a planet that’s at its brightest. Uranus will reach magnitude 5.7 on the 28th, when its disk will measure 3.7″ across.

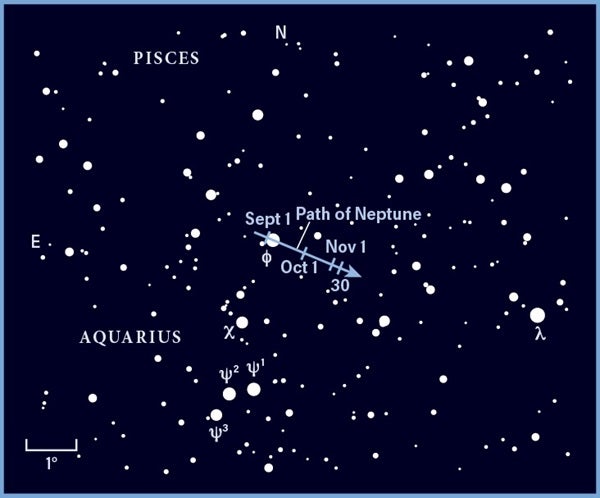

Neptune reached opposition September 10, when it shone at magnitude 7.8 and its disk was 2.4″ in diameter. However, Neptune’s brightness doesn’t vary much, so it will only be a few hundredths of a magnitude fainter by the time Uranus reaches opposition.

The orbit of Uranus tilts less than 1° from the plane of the ecliptic, so you’ll always find it close to that line. Uranus’ average apparent motion (against the background stars) is approximately 42″ per day. It takes Uranus about 44 days to move the width of the Full Moon. Uranus currently lies in front of the stars of Aries the Ram. To find it, look 10.5° south-southeast of magnitude 2.0 Hamal (Alpha [α] Arietis).

Observing Uranus

The visible atmosphere of Uranus is generally a featureless haze. But throughout the planet’s history, many observers have seen its details. The first such observer, British astronomer William Buffham, noticed two round bright spots and a bright zone in 1870. In 1883, American astronomer Charles Augustus Young reported markings, along with both polar and equatorial belts. These details, unfortunately, have one thing in common: They were exceedingly faint.

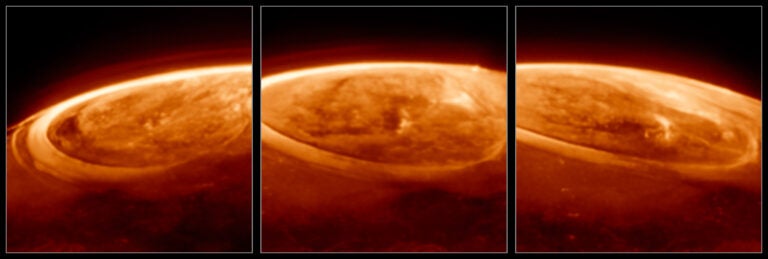

Even the Voyager 2 mission that flew past Uranus in January 1986 showed a nearly featureless globe. The best recent detail-bearing images of Uranus have come courtesy of the Hubble Space Telescope. The visible-light images reveal a bright south polar zone, dark clouds, and several faint light and dark bands.

Viewed through almost any telescope, Uranus appears as a greenish (greenish-blue through large apertures), featureless disk. At high power, you might detect that it’s slightly elliptical because of its rapid rotation. However, because the disk is so small and most of us don’t enjoy perfect seeing, it’s difficult to see any of the planet’s details.

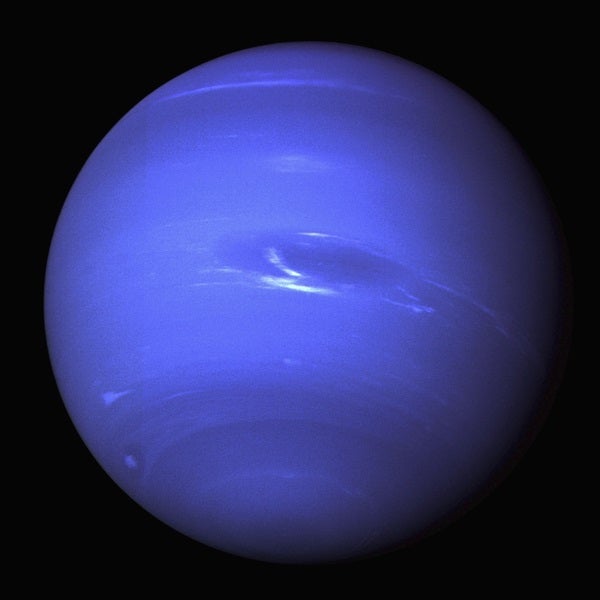

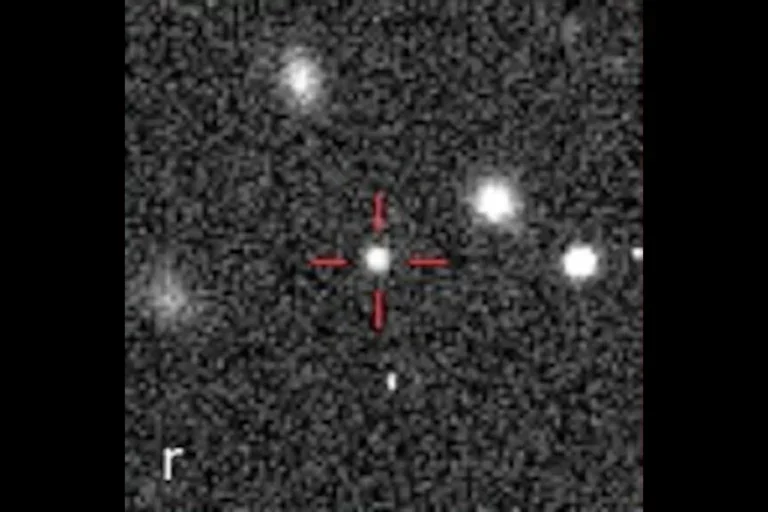

Neptune isn’t hard to find for an amateur astronomer with a medium-size telescope. It presents a small bluish disk that’s always out of the range of naked eyes. Locating it is more problematic through small optics. If you have a 3-inch or smaller scope or are using binoculars, first verify the planet’s position against the background stars by using the chart on page 53.

A telescope won’t reveal much in the way of surface features on Neptune’s tiny disk, although you should be able to see its largest moon, Triton. Basically, an amateur astronomer can’t do much better than identifying the planet among countless background stars. The thrill to observing Neptune is simply finding it.

Observing outer moons

Merely spotting the ice giants may be enough satisfaction for some novice observers, but if you’re in the mood for something a bit more difficult, why not try to spot one of these worlds’ satellites? Plan to spend some serious time on this task. Although the planets are relatively easy to find, their moons are quite hard to pick out from the starry background.

These moons’ faintness is only part of the problem, however: None strays far from its host. Oberon never appears more than 44″ from Uranus (about 12 planetary diameters away) while Titania maxes out at 33″ (nine time Uranus’ diameter). Triton is the easiest of the three to see, even though it always remains within 17″ of Neptune (not quite 7.5 Neptune diameters). It leads because it glows slightly (20 percent) brighter than the others and Neptune produces much less glare than Uranus.

The key to finding any of these moons is knowing how, when, and where to look. First, choose a dark observing site where the seeing (atmospheric steadiness) is good. Turbulence in Earth’s atmosphere will cause planetary images to appear mushy and wash out these faint moons entirely.

You’ll also want to avoid glare from Earth’s Moon. Try to observe within three or four days of a New Moon, which occurs September 28, October 28, and November 26.

After you decide when you want to look for the moons, calculate for each moon how much time has elapsed since the previous elongation. For example, if you plan to observe at 10 p.m. EDT the night Uranus reaches opposition (October 28), you’ll find Titania’s previous northern elongation occurred on the 27th at 1 a.m. EDT, so one day and 21 hours have elapsed. Similarly, seven days and four hours have passed since Oberon was at its greatest elongation.

Then use the diagram to figure out approximately where on its orbit each moon lies. The farther from Uranus a moon appears, the easier it will be to see. The illustration shows south at top to match the view through most telescopes when the planet lies highest in the south.

The same technique works for Triton. For it, the table lists greatest eastern elongations because the moon lies farthest from Neptune at that point and at the opposite side of its orbit. If you observe on October 28 at 10 p.m. EDT, the moon will be five days and three hours along its orbit. If you see a faint speck in this position, you’ve found Triton.

If these moons don’t offer enough of a challenge, Uranus has two harder-to-see satellites that will really test your observing acumen. With a 16-inch telescope, an eyepiece that gives a magnification above 250x, and excellent viewing conditions, you just might glimpse the smaller satellites Ariel and Umbriel. Ariel glows at magnitude 13.2 but remains within 14″ of Uranus (3.75 diameters). Magnitude 14.0 Umbriel never appears more than 20″ from the planet (5.5 diameters). Use planetarium software to pinpoint their positions before you begin your search.

Whether you want to hunt down the ice giants for the first time through binoculars or haul out your big scope and closely examine these worlds searching for faint moons, you’ll get an observing thrill that’s hard to beat.

Good luck!