Now, new results across multiple fields of astronomy are causing many to question the existence of this spike. Some scientists argue that the LHB may not have come so late. Instead of a surge in impacts, the terrestrial bodies — including the Moon and Earth — probably suffered a more general decline of collisions as they swept up the last pieces of planetary debris.

A sudden burst of collisions

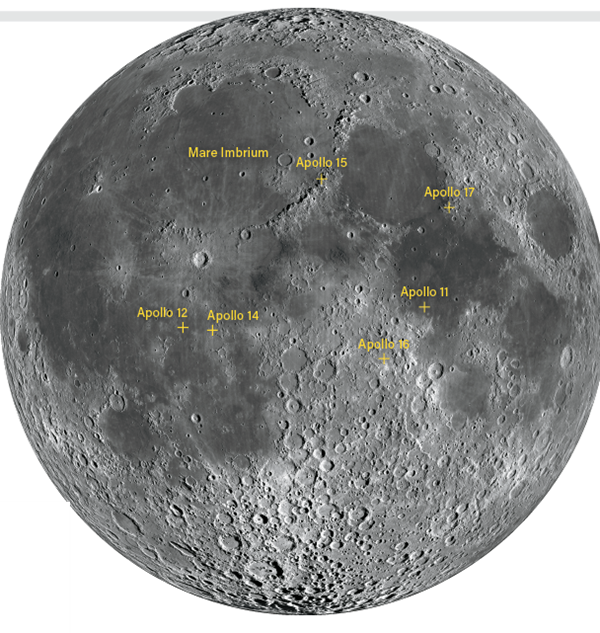

Before Apollo astronauts landed on the Moon, astronomers could gauge only the relative ages of craters to determine which came first and which were more recent. The solar system is about 4.5 billion years old, and if the Moon formed at that point — or soon after — then the oldest craters should be roughly the same age. But the Moon rocks revealed ages closer to 3.8 billion and 3.9 billion years. And it looked as though one of the Moon’s biggest impact basins, Mare Imbrium, was about the same age as another large basin, Mare Orientale. “It was really surprising,” says Nesvorny.

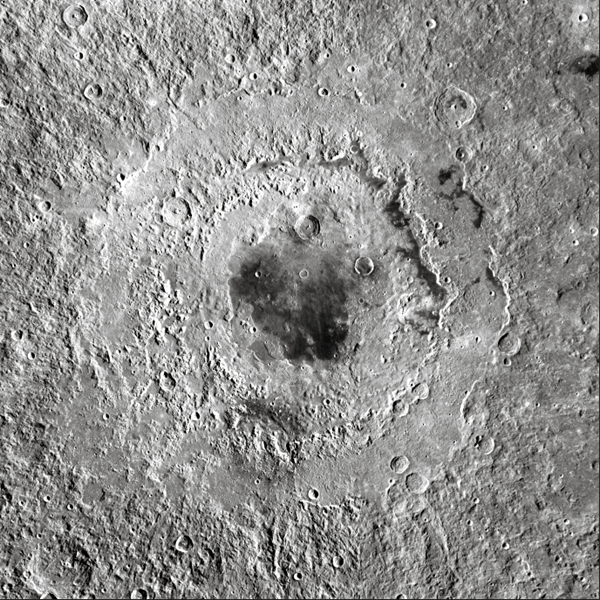

Other reports initially suggested there was no evidence for lunar impacts older than the returned lunar samples. To explain why the Moon would have suffered at least two massive collisions — estimates put the Imbrium impactor at 150 miles (240 kilometers) across, the size of a planetary embryo — so late in its lifetime, scientists in the 1970s raised the possibility of a cataclysm or spike. Something must have stirred up the solar system’s loose rocks and sent them flying toward the Moon.

Another key factor supporting the LHB was the relative amounts of highly siderophile, or iron-loving, elements (HSEs). Iron and the elements with which it bonds tend to sink into a world’s core, causing the body to differentiate and leaving a surface relatively depleted in such substances. But subsequent collisions with smaller, undifferentiated objects can provide a fresh source of these elements to the surface. Scientists expected Earth to be 20 times more abundant in HSEs than the Moon, based simply on their relative sizes. Instead, our planet contains roughly 1,000 times more HSEs than its satellite, for reasons that long remained mysterious.

Lunar samples

Although the Apollo samples allowed scientists to determine the age of individual Moon rocks, the question of their source lingered. The astronauts picked up most of the material from the ground, but the rocks didn’t necessarily form where they were found. On Earth, rocks can break off the sides of mountains or be carried away by rivers, glaciers, or the wind. Although the Moon never boasted liquid water and no winds weather the lunar landscape, it had another method of moving rocks around — impacts.

When an object flying through space crashes into our satellite, it gouges out enough of the crust to form a crater. The excavated material must go somewhere. With the Moon’s low surface gravity, most of it tends to end up in space. But that same low gravity allows debris to fly much farther across the lunar surface than it would on Earth. In recent years, some scientists have begun to question whether most of the samples came from the same source — the massive Imbrium impact. That would explain the similarities in the samples’ ages.

A key development came when NASA flew a geologist to the Moon on Apollo 17. Astronaut Harrison “Jack” Schmitt wasn’t satisfied with collecting rocks off the surface. Instead, he removed a sample from a large boulder in the Taurus-Littrow region at the southeastern corner of Mare Serenitatis. “Jack knew what he was looking for,” says Bill Bottke, a lunar scientist at SwRI. The sample revealed an age between 3.8 billion and 3.9 billion years.

But Schmitt’s massive rock may not have been source material. According to Bottke, in the last decade or so, scientists have begun to question whether that boulder originally came from Serenitatis or whether it flew over from the Imbrium impact. “It’s a tricky business,” Bottke says.

More recent spacecraft have helped improve our understanding of lunar cratering history. Missions such as the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter and the Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory have allowed investigators to reevaluate how impacts affected the Moon over time. “Craters not visible to the naked eye are visible [to the spacecraft],” says Nicolle Zellner, an astronomer at Michigan’s Albion College. Some of these covert impact scars are enormous, up to 185 miles (300 km) across, though they’ve eroded away. The presence of these early giant craters means that massive objects bombarded the solar system longer than previously calculated, which affects our picture of how the collisions trailed off over time.

Proponents of a slowly declining bombardment rate point not only to younger craters but also to the gradual emergence of evidence for older impacts. As instruments have become more precise, they can measure smaller and smaller amounts of the elements that help researchers date the rocky samples. “Both in Apollo samples and lunar meteorites, we see evidence for impacts older than 3.9 billion years,” Zellner says. “That kind of improved sensitivity in instruments is allowing us to refine our interpretation of the data as well. When you take all of those pieces together, they point to something that was not a cataclysmic bombardment in a very short period of time.”

Based on the Moon rocks and lunar meteorites, our satellite appears to have far less of these precious elements than it should. A spike in impacts was one of several reasons put forth to explain this deficit. New research suggests that such a cataclysm might not be required. Researchers simulated impacts at different velocities and found that the Moon retains material from large impactors less effectively than it does from smaller colliding bodies. This means our satellite would lose more of these iron-loving elements before they could ever accumulate on its surface. The scientists concluded that the Moon probably held on to one-third as much HSE-rich material than previously estimated.

In addition, they suspect that roughly half of this material sank into the core before our satellite’s mantle crystallized. Because Earth’s mantle crystallized more quickly, our planet’s crust retained a higher percentage of iron-loving elements. “The late crystallization overturn sequesters HSEs,” says Alessandro Morbidelli, an astronomer at the Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur, in France. “Because of late sequestration, it’s clear we don’t need an impact spike 4 billion years ago.”

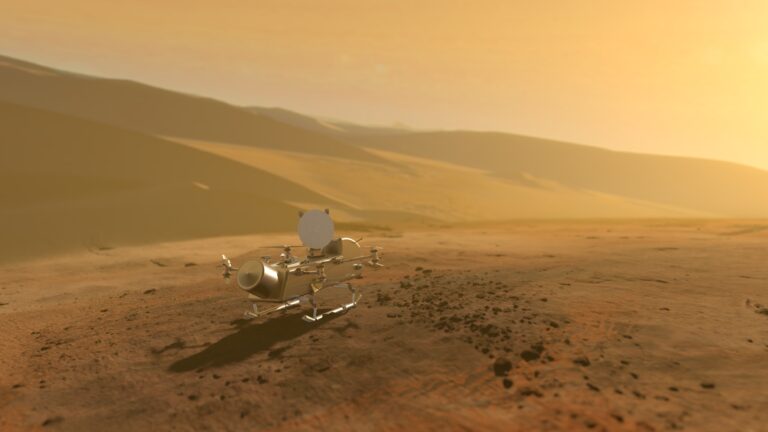

Red scars

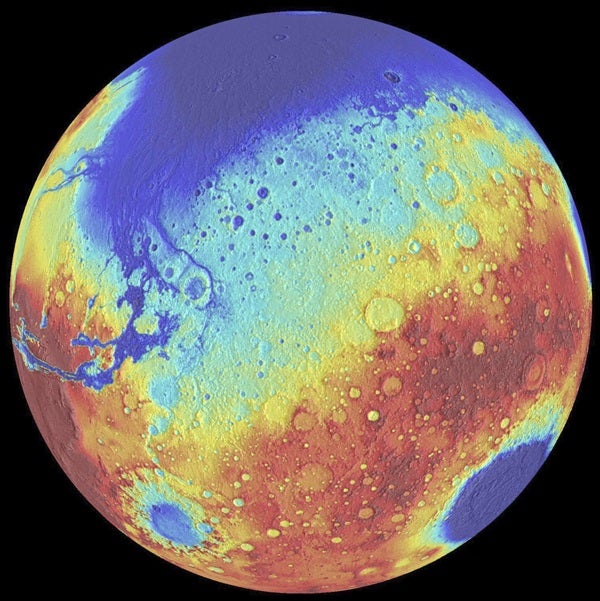

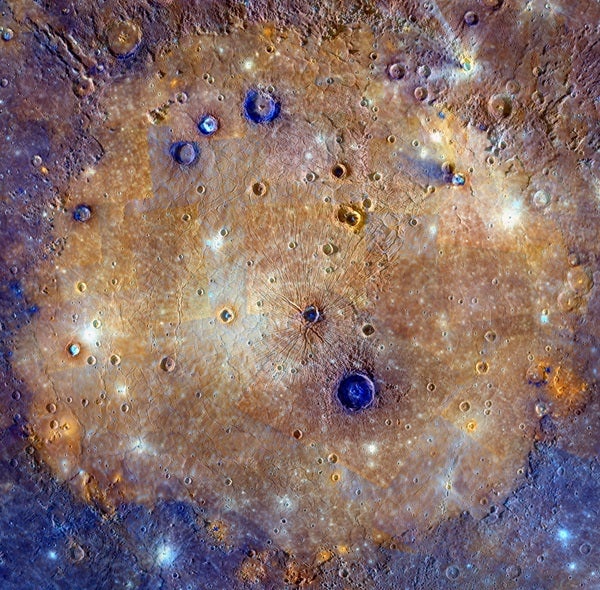

The Moon’s surface isn’t the only place capable of preserving the imprint of the solar system’s past. Mars is also a relatively unchanging target. Although it likely once harbored oceans of water, the Red Planet lost most of this liquid early in its life, leaving behind a dry surface with little water to erode its bombardment history. Mars also lacks plate tectonics, which erase impact signatures on Earth. “If we want to understand impacts on the Moon, we have to solve Mars simultaneously,” says Bottke.

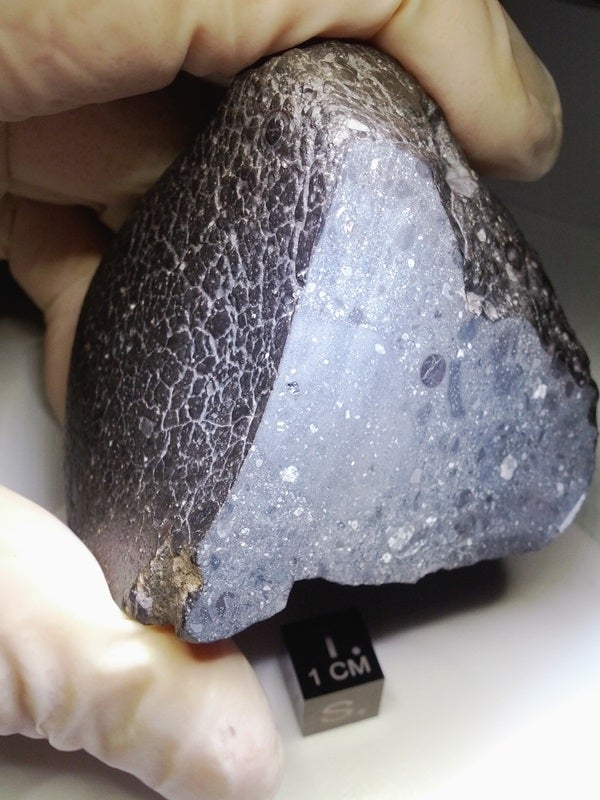

While neither spacecraft nor astronauts have returned samples of Mars to Earth, the Red Planet has obligingly shipped some of its rocks to our world in the form of meteorites. The Northwest Africa 7034 meteorite, nicknamed “Black Beauty,” came from the southern highlands and is unique among martian meteorites. Black Beauty is the only known breccia, a rock composed of bonded mineral fragments. “This is a collage of welded fragments of rocks from different places on Mars all cemented together,” says Desmond Moser of Canada’s Western University in London, Ontario.

Moser and his colleagues recently studied tiny zircons — minerals that form when lava cools — as well as the mineral baddeleyite hidden inside Black Beauty. From studies of meteorite craters on Earth, scientists know that the heat and pressure of an impact rapidly reshape most rocks. Zircons, on the other hand, react incredibly slowly to change. “Once something affects them, they really have incredible memories of those events,” Moser says. Baddeleyite, on the other hand, changes predictably when exposed to high pressures.

Although Bottke agrees with most of Moser’s conclusions, he isn’t completely convinced that Black Beauty’s unchanged zircons spell the end of bombardment on the Red Planet. “Mars is a big world, much bigger than the Moon,” he says. It’s possible that significant impacts occurred but that their pressure and temperature waves avoided hitting Black Beauty.

A dance of giants

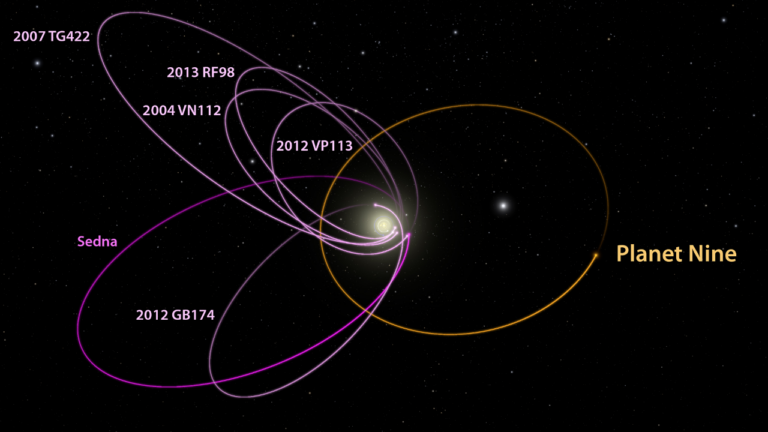

In the past few years, the Nice model has continued to evolve. The original model, which focused on the birth of ice giants in the outer solar system, was linked to the LHB through timing. As Uranus and Neptune performed an intricate dance in the outer solar system, Neptune bulldozed through the young Kuiper Belt, which was originally much larger than it is today. The marauding planet flung some of these cometary bodies out of the Sun’s domain while hurling others into the inner solar system. In addition to colliding with the Moon and rocky planets, the cometary material may have stirred up the asteroid belt, sending some of these rocky objects inward as well. “You have both asteroids and comets,” says the University of Arizona’s Kathryn Volk, a planetary scientist who studies small bodies in the outer solar system. “That always mixed up the story.”

“Dynamically speaking, I’d never been very satisfied with this late instability,” says Sean Raymond, a planetary modeler at France’s Laboratoire d’Astrophysique de Bordeaux. “If things are going to go bonkers, they do it right away.” Sometimes unusual things happen, but scientists prefer not to rely on rare exceptions as explanations.

Nesvorny described his concerns a bit more tangibly. If you set a coin on the edge of a table, it’s relatively easy to place it so that it immediately falls off. “It’s hard to put it on the edge so that it falls an hour from now,” he says. But that’s what an LHB-triggering Nice model seemed to suggest.

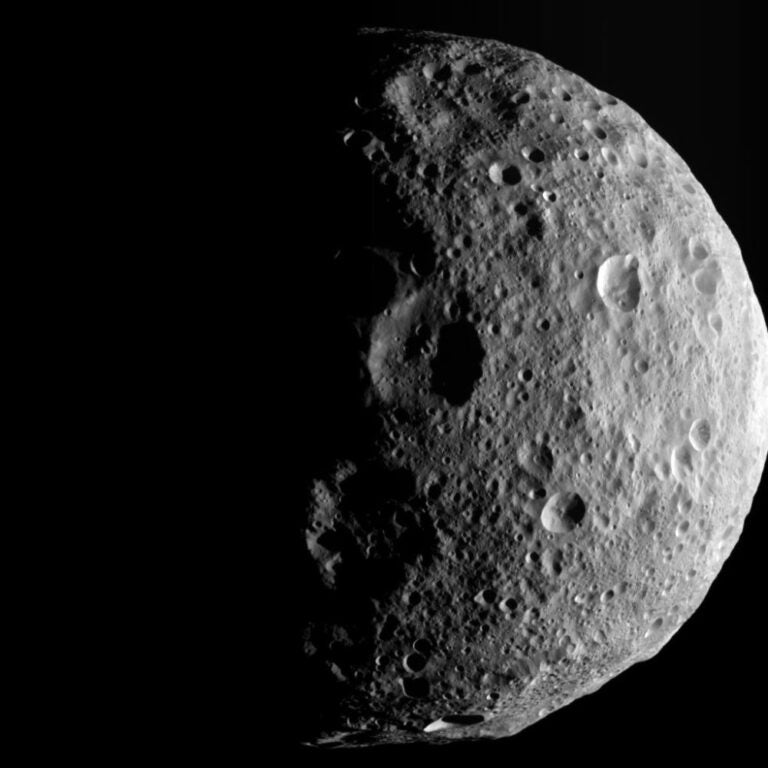

Nesvorny began to investigate ways to time-stamp the planetary dance. Astronomers think the Kuiper Belt is responsible not only for the icy debris it holds on to today and the short-period comets that periodically swoop in from the solar system’s outskirts, but also for the irregular moons around some of the giant planets and Jupiter’s Trojan asteroids. This latter group comprises thousands of objects that orbit the Sun in stable locations positioned 60° in front of and behind the gas giant. Of the more than 7,000 Trojans scientists have identified, roughly 25 are larger than 60 miles (100 km) across. Two of these form the binary pair of Patroclus and Menoetius.

Patroclus and Menoetius — targets for NASA’s Lucy mission to Jupiter’s Trojans in 2033 — orbit each other at a distance of 415 miles (670 km). Scientists suspect the pair came together in the Kuiper Belt in roughly the solar system’s first 10 million years, then traveled inward when things became unstable. But how long did they spend in the Kuiper Belt before embarking on their journey? To find out, Nesvorny modeled how long it would take the pair to become separated during the interactions of the pre-Nice Kuiper Belt. The longer the binary sat in the belt, the more collisions it would have endured, breaking their connection. Nesvorny and his colleagues wanted to know what the odds were that 1 in 25 such binaries would remain stable. They found that the Trojan binary had to have been ejected from the Kuiper Belt within 100 million years of its formation.

An early instability makes sense. According to Raymond, the most natural trigger for the planetary movement was the loss of the gas disk in which they were born. Within roughly 10 million years, most of the gas had either been swept up by the planets or dispersed by the Sun. The gas would have had a dampening effect. Once it was gone, the planets could more easily tug at one another gravitationally, changing their orbits. Nesvorny’s 100 million years was an upper limit, with the circumstances that he modeled among the most optimistic.

That doesn’t necessarily mean there wasn’t an LHB — only that if there was one, the rearrangement of the ice giants didn’t set it off. However, the Nice model was the best argument for causing an LHB, so the demise of this connection makes yet another argument against the hypothesis.

Not ready to give up

The chatter among the scientific community makes it seem as though time has run out for the LHB. Perhaps there wasn’t a sudden increase of material slamming into the terrestrial planets after all, only the last of the debris that had built the planets being slowly swept up by collisions. Case closed, right?

Bottke isn’t completely sold. “There’s things that still need to be worried about,” he says. He wants to know why Mare Imbrium and Mare Orientale, both huge basins, formed at the end of the line. Statistically, the largest rocks should have collided the earliest, leaving the more numerous smaller objects to make the final scars. More large impacts at the end can come from a spike in collisions, a change in the characteristics of the colliding population, or just bad luck. “What are the odds of two of the biggest [collisions] at the end of the line?” he asks. “I think that’s going to be a really low probability number.”

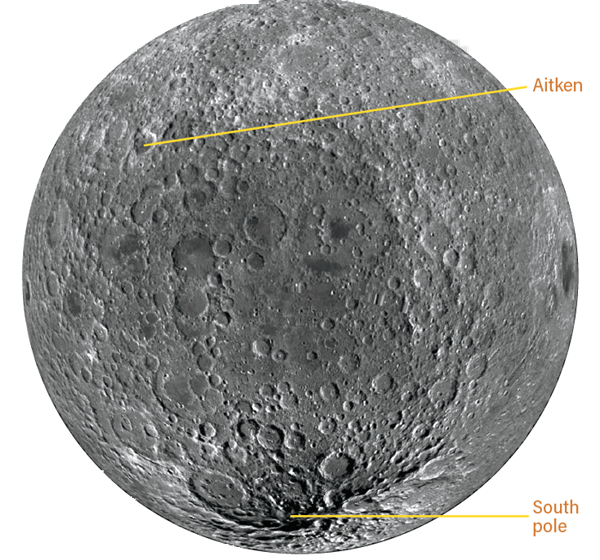

The South Pole-Aitken Basin, the largest and oldest impact feature on the Moon, is another location with a mysterious age. According to Bottke, estimates range from 4.1 billion to 4.5 billion years. Nailing down its age would be “a big deal,” he says. If it’s only 4.1 billion years old, why don’t we see signs of the craters that should have formed earlier in lunar history? Although several researchers have suggested that some process erased the most ancient craters, he remains unconvinced. “It’s not enough to just get rid of basin rims,” he says. “You have to get rid of gravitational signals and any compositional differences you have.” He’s not certain those changes are showing up on the Moon.

Finally, he points to concerns with meteorites. Meteorites from the Moon and the asteroid belt show signs that their parent bodies lost gas as a result of impact shock waves in two episodes — one around 4.5 billion years ago and the other between 3.5 billion and 4 billion years ago — but remain strangely quiet between 4 billion and 4.5 billion years ago. Bottke says this points to two components of inner solar system bombardment.

“I’m not quite ready to give up,” he says.

One of the best ways to settle the debate over whether Earth and the Moon suffered from increased collisions early in their lifetimes would be to return to the Moon for more samples. NASA didn’t select the Apollo landing sites for the purpose of nailing down crater ages, but perhaps that could be a key consideration on the next trip. Right now, NASA considers the South Pole-Aitken Basin a top choice for future landing sites. Confirming the basin’s age could help to unravel some of the mystery surrounding the history of lunar bombardment.

“If we can be more selective and careful about landing sites that give us samples from the impact basin, they can help us to fill in some of the questions we still have,” Zellner says.

With those ages in hand, perhaps scientists will be able to nail down what happened in the early solar system, revealing the end game of planet formation and perhaps unveiling when life could have first arisen on Earth and, perhaps, Mars.

“It’s an exciting time of confusion,” Morbidelli says. “Stay tuned.”