Key Takeaways:

- ‘Oumuamua, the first interstellar object detected in our solar system, exhibited a reddish hue and a highly elongated shape (6-10 times longer than wide), unlike any object previously observed within our solar system.

- Its trajectory indicated a non-gravitational acceleration, initially attributed to outgassing, although the absence of a detectable coma or tail and unusual lack of CN gas challenged this explanation. Alternative hypotheses, including a low-density structure or a solar sail, were considered but deemed less likely.

- Observations revealed ‘Oumuamua's rotation, with a complex tumbling motion along its shortest and longest axes, occurring every 8.7 and 54.5 hours, respectively.

- Despite limited observational time, ‘Oumuamua provided valuable insights into the potential composition and origin of interstellar objects, prompting further investigation into the ejection mechanisms from other star systems and highlighting the need for future surveys to increase detection rates.

That night, a faint, thin streak appeared in a 45-second-long image snapped by the University of Hawai‘i’s Pan-STARRS1 Telescope on Maui. The next morning, postdoctoral researcher Robert Weryk spotted the streak and compared it to an image taken the day before. The object was there, too. It was moving steadily across the sky, covering about 6.2° each day.

By October 22, two things were clear: The object was on a hyperbolic orbit, meaning it comes close to our Sun only once and then shoots away again, never to return. And, based on its orbit, it did not originate in our solar system at all, but instead came from another star system.

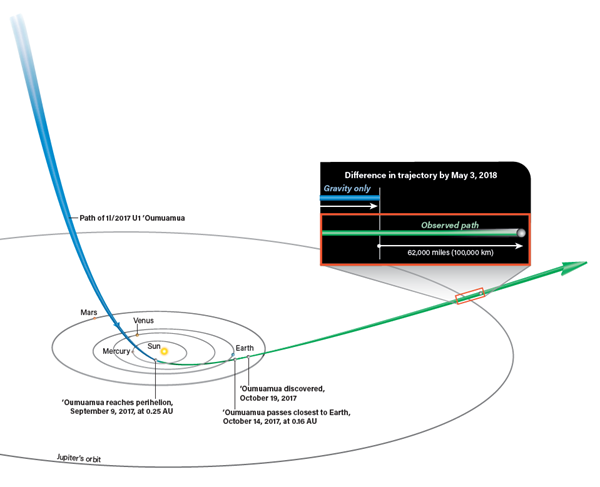

Strange space rock

Weryk spotted ‘Oumuamua less than a week after its closest approach to Earth, when it had come within 0.16 AU of our planet, more than 60 times the distance to the Moon. It had passed perihelion — its closest point to the Sun — more than a month before, flying within 0.25 AU of our star on September 9, 2017. ‘Oumuamua had entered the solar system moving about 16 miles (26 kilometers) per second and swung around the Sun at nearly 55 miles (88 km) per second. Even the Hubble Space Telescope would lose the ability to spot it after January 2018.

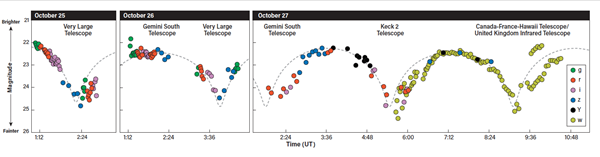

Between October and January, astronomers scrambled to observe ‘Oumuamua with as many telescopes as possible. In all, more than 800 observations were made. Researchers started by measuring the light it reflected, which over time allowed them to create a light curve that showed how it rotates in space, as well as offered clues to its size and shape.

‘Oumuamua’s reflected light also showed it is tumbling through space, turning on its shortest axis every 8.7 hours and spinning on its longest axis every 54.5 hours. This type of motion is common among small solar system asteroids, particularly those of ‘Oumuamua’s size, but astronomers can’t tell whether the object has been spinning like this since it left its home or if the complex rotation is more recent.

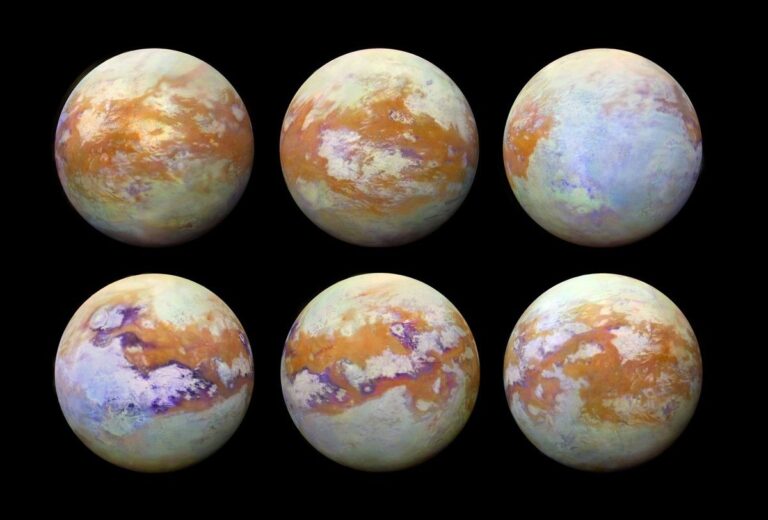

Its surface is red, which is typical of several classes of objects in our solar system, including comets; D-type asteroids, which are found in the outer main belt or sharing Jupiter’s orbit; and bodies past Neptune, known as trans-Neptunian objects. But ‘Oumuamua’s color reveals frustratingly little about its composition because several factors can turn a body red: patches of organic material, including the tholins that color worlds such as Arrokoth; iron deposits on the surface; or space weathering, in which exposure to factors such as micrometeorites and sunlight alter a body’s properties over time.

Migrating jets

Some calculations showed that normal comet outgassing at the rate needed to match ‘Oumuamua’s motion would actually cause it to spin too quickly and ultimately fly apart. But this conundrum was solved in a May 2019 study published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters led by Darryl Seligman of Yale University, which proposed ‘Oumuamua had “migrating jets.” As ‘Oumuamua twirled, the study says, the portion of its surface directly heated by the Sun would shift. If only that Sun-warmed area produced a jet, then it would cause ‘Oumuamua to gently rock back and forth like a pendulum on one axis as the region undergoing outgassing shifted. Such motion, the team calculated, could produce the light curve astronomers saw. This is because often, many different types of motion can create the same type of light curve, making it difficult to distinguish between possible scenarios without more information. Seligman’s work suggested that if ‘Oumuamua is a comet, it likely lost about 10 percent of its total mass through outgassing on its journey through our solar system.

Asteroid or comet?

Astronomers expected the first identified interstellar visitor would be a comet. That’s because comets, for their size, are brighter than asteroids, which makes them easier to spot. In our solar system — and likely others — incoming comets originate far from the Sun, where they’re easier to knock loose as the star’s gravity wanes with distance.

Many comets also have orbits that are highly eccentric. A perfectly circular orbit has an eccentricity of 0, elliptical orbits fall between 0 and 1, and orbits with eccentricities greater than 1 are hyperbolic, or non-returning. ‘Oumuamua plunged into the solar system from above the ecliptic plane in which the planets orbit with an eccentricity of 1.2, meaning it would slingshot right through the solar system and never return. The most eccentric solar system comet, C/1980 E1, has an eccentricity of nearly 1.058 — it was freed from the Sun’s gravity by an encounter with Jupiter. But ‘Oumuamua’s eccentricity was so much higher, it indicated the object came not from the Kuiper Belt or Oort Cloud, but another star entirely.

The Minor Planet Center initially classified ‘Oumuamua as a short-period comet on October 20, says Karen Meech of the Institute for Astronomy at the University of Hawai‘i, a member of the team that discovered and first studied ‘Oumuamua. On October 24, with more orbital information, ‘Oumuamua’s classification was updated to C/2017 U1 — a long-period comet. But ‘Oumuamua had already swooped around the Sun by the time it was discovered with no tail in sight. Meech’s team contacted the Minor Planet Center, which then reclassified ‘Oumuamua by October 26 as A/2017 U1, using the A designation indicating a long-period comet orbit, but no coma or tail, Meech says. Ultimately, the astronomical community developed a new naming system for interstellar objects, christening the discovery 1I — the first interstellar object.

Then, a June 2018 Nature paper led by Marco Micheli of the European Space Agency’s Space Situational Awareness Near-Earth Object Coordination Centre in Frascati, Italy, reported that ‘Oumuamua was not moving as an asteroid should. Instead, ‘Oumuamua’s path indicated a “really strong nongravitational acceleration,” says Meech, who is also a co-author on the paper. That meant gravity was not the only thing dictating ‘Oumuamua’s motion. Something was causing it to speed up as it departed the solar system.

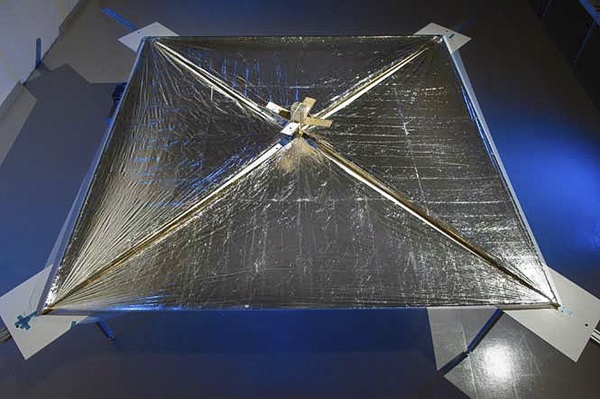

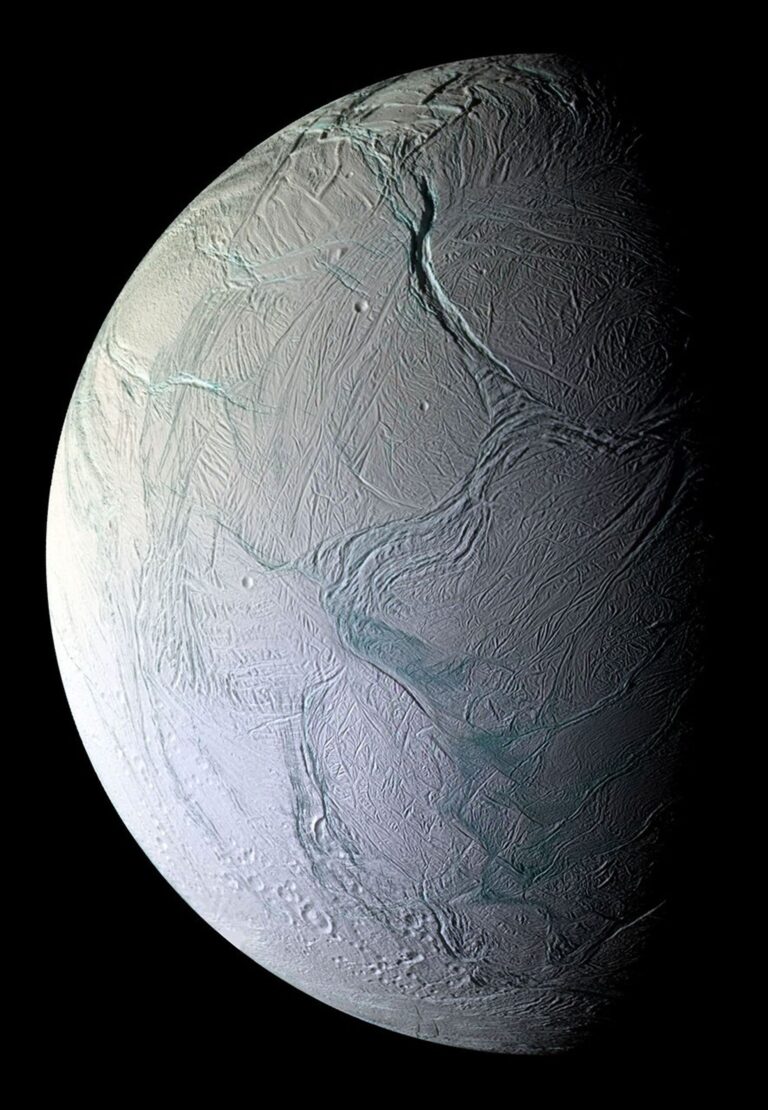

One by one, they ruled out these scenarios. Friction or drag would pull it toward the Sun, not speed it up in the opposite direction. Images of ‘Oumuamua showed no additional objects large enough to affect its motion in the way astronomers saw. And even a high magnetic field would not cause enough interaction with the Sun’s charged particles to push ‘Oumuamua as observed. For solar photons to push ‘Oumuamua hard enough, the space rock would need an incredibly low density, like that of aerogel, a substance that can be up to 900 times less dense than water. Or, speculated Shmuel Bialy and Abraham Loeb of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, ‘Oumuamua could be incredibly thin with a large surface area — like a solar sail.

Although the idea that ‘Oumuamua is an alien spacecraft or abandoned extraterrestrial technology is certainly exciting, Meech and others argue it is extremely physically unlikely, especially given that one explanation the team investigated did work quite well: “The only thing that was left, which was the most logical, is that it’s outgassing,” Meech says.

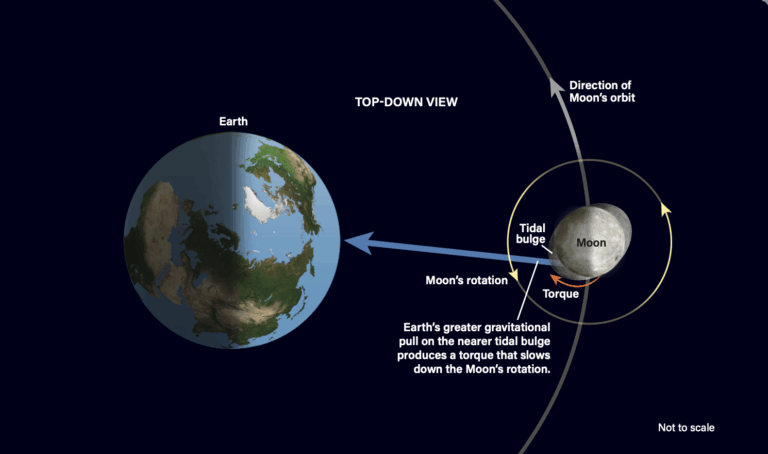

Outgassing is the escape of gas and dust as ices on the surface of a comet sublimate, turning directly from a solid to a gas as the object approaches the Sun and heats up. The escaping gas gives the comet an extra push in the opposite direction. “This was the same level of strength as you would typically see in comets,” says Meech of ‘Oumuamua’s acceleration, if it were losing about 2.2 pounds (1 kilogram) of material each second. Based on what we know about solar system comets, that’s not unusual. And, after all, astronomers had expected ‘Oumuamua to be a comet in the first place.

But ‘Oumuamua still had no tail, even in the deepest observations. Meech was part of a team looking for gas escaping ‘Oumuamua, including CN, CO, CO2, and H2O. CN gas, which is bright and easy to spot, gets dragged off comets in our solar system when water leaves the surface, Meech says. It can be used as a proxy for water, which is harder to observe. The team also expected a fair bit of CO and CO2 because, as ‘Oumuamua zipped farther from the Sun, temperatures dropped and water became harder to sublimate from the surface.

The researchers tracked ‘Oumuamua for 30 hours with the infrared-seeking Spitzer Space Telescope, but nothing showed up. That was strange, because they expected “a fair bit” of gas, particularly water — and, thus, CN — to be escaping if ‘Oumuamua’s acceleration was due to outgassing, Meech says.

Still, Moro-Martín’s paper concludes, “There are many open questions that need to be addressed in order to assess the viability of this scenario,” such as how such a porous object might survive not only ejection from its solar system, but also its journey through interstellar space. And Meech’s team deemed that unlikely: “We have no examples of anything like that in the solar system. While theoretically plausible on a mathematical scale, it’s not physically sensible,” Meech says.

“It’s always a little bit tricky to interpret too much out of not seeing something,” she cautions. But still, “it’s not quite hanging together as a typical comet.”

When gas escapes from a comet, it generally carries surface dust with it; the stronger the outgassing, the larger the grains of dust it can liberate. Meech’s team also looked for dust, but spotted none. But even that doesn’t kill the comet theory — Meech says that even if the comet was devoid of small dust, large dust could have been coming off the surface. Large dust is harder to see at visible wavelengths, where they were looking.

She and her colleagues conclude that ‘Oumuamua is a comet, albeit an unusual one, with chemistry unlike that of the comets we see in our solar system. “But that’s nothing surprising,” Meech says. “It’s coming from a different star system.”

What does ‘Oumuamua tell us?

With so much unknown, it may seem there is little ‘Oumuamua can teach us. Admittedly, ‘Oumuamua is a sample size of just one. But even one object can tell astronomers a lot, especially when compared to their expectations of what the first interstellar visitor would be like.

“ ‘Oumuamua is probably an ejected planetesimal or building block from the birth process of planets,” Meech says. As such, its discovery has implications for the number of such objects available for us to find. That’s because Pan-STARRS, which discovered ‘Oumuamua, began full science operations in May 2010 and was expected to see few, if any, interstellar objects larger than 0.6 mile (1 km) after 10 years of operation. Researchers mainly hoped to put a limit on the number of interstellar objects passing through our solar system, particularly smaller ones like ‘Oumuamua.

As more surveys put eyes on the sky, astronomers are able to estimate, based on the amount of sky being covered and the rate at which they expect bodies to be ejected from around other stars, how many and what kind of interstellar interlopers we should see.

But the expected numbers depend on several factors, from an object’s size — ‘Oumuamua is smaller than our first expected find — to the rate at which planetary building blocks are tossed out of their home systems. The latter depends on even more factors, such as the size of the system, the number of giant planets available to scatter objects away, and whether other stars have passed close enough to nudge objects out of distant orbits around their suns.

What ‘Oumuamua did reveal was that, based on its speed and trajectory, it is likely young and has been journeying between stars for only about 2 billion years, less than half the age of our solar system. Coryn Bailer-Jones of the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg, Germany, calculated ‘Oumuamua’s track — which originated in the direction of Lyra the Harp — back to before it first entered the solar system. His calculations rewound the clock several million years to compare ‘Oumuamua’s path to the past positions of 7 million stars in the Milky Way measured by the Gaia satellite. Because stars are moving in the galaxy over time, he had to rewind their orbits, in addition to ‘Oumuamua’s, to look for places where the two might reasonably overlap.

The high speed would be more likely, she says, if ‘Oumuamua came from a binary star system. But none of the four candidates are binaries. “So, while these were our best candidates, none of them stood out as, ‘This is it! This is the home system!’ ” she says. The next Gaia data release — expected in late 2021 — may help, allowing astronomers to trace back the motions of even more stars and possibly find better candidates. “It would be great to revisit this in a couple of years,” Meech says, when more data are available. But for now, astronomers are unable to pin down just where ‘Oumuamua came from.

Why didn’t we see ‘Oumuamua sooner?

If ‘Oumuamua entered the solar system almost two centuries ago, why did it take astronomers this long to see it?

‘Oumuamua’s trajectory brought it down from above the plane of the solar system. That’s an unusual and unexpected place to search for near-Earth objects, which is exactly what the Pan-STARRS1 Telescope was tasked with when it spotted the interloper. In the time shortly before its discovery, ‘Oumuamua was just coming out of solar conjunction, when it was hidden behind our star. “You’d have to be pointing your telescopes really close to the Sun,” to have seen it, says Meech, “which you don’t do.”

Additionally, ‘Oumuamua is small — and therefore faint. Prior to solar conjunction, it was simply undetectable by any telescope, including Hubble. Although one pre-discovery image taken by the Catalina Sky Survey on October 14 shows ‘Oumuamua, Meech says, even then it is too faint to pick out without knowing it’s already there. “If you know there’s something there, then you can actually see it. You can see it moving, and it’s moving at the right rate in the right direction, but you would’ve never picked it up on its own,” she says.

Only the beginning

Since the last Hubble observations in January 2018, ‘Oumuamua has been beyond astronomers’ reach. According to Meech, ‘Oumuamua should reach the Kuiper Belt in about 2024 and pass its edge in late 2025. ‘Oumuamua will pass the most distant location the Voyagers have reached in about 2038. By 2196, it will again be 1,000 AU from the Sun, although our Oort Cloud is projected to extend beyond 100,000 AU. So, when ‘Oumuamua truly passes the “edge” of the solar system, she says, depends on where you define that edge.

Although it is gone from sight, it is not out of mind. Astronomers worldwide continue to speculate on the mysteries that remain. “We really wanted to know what [‘Oumuamua] was made of. We wanted to know its chemistry. And that experiment couldn’t be done well,” Meech says. “But finally, for ‘Oumuamua, it had that very strange elongated shape. And to me, that was one of the biggest puzzles that we couldn’t solve.”

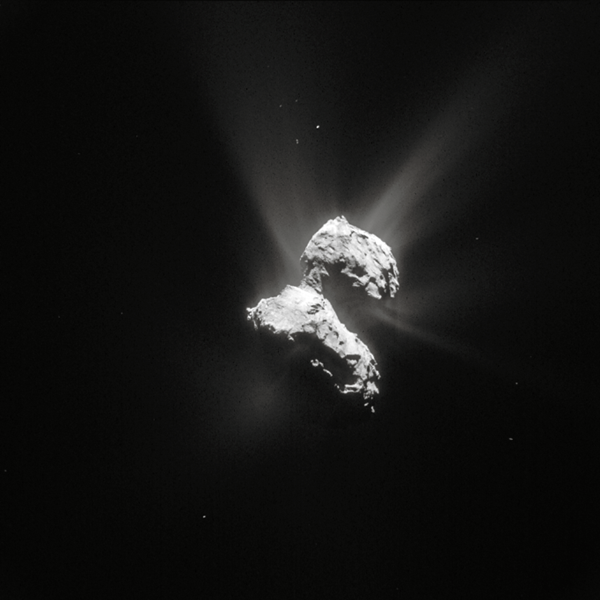

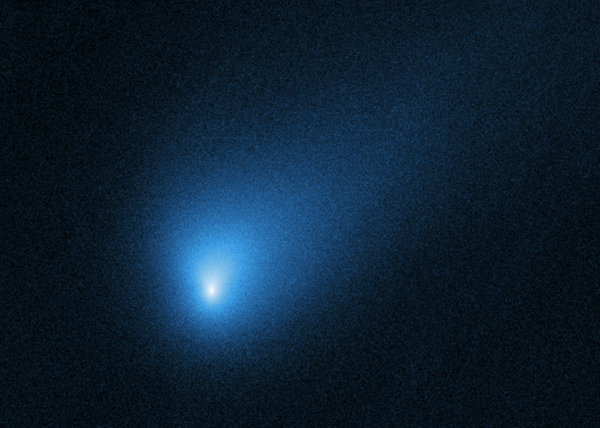

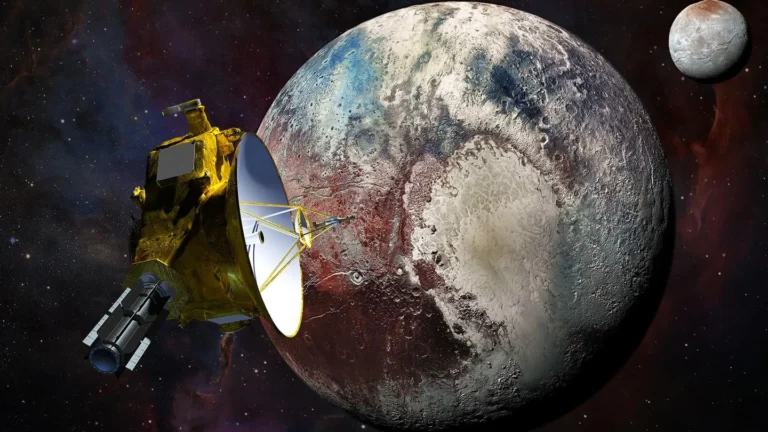

Now it appears ‘Oumuamua is not alone. On August 30, 2019, amateur astronomer Gennady Borisov at the MARGO observatory in Nauchnij, Crimea, spotted a new comet moving through the sky. Designated 2I/Borisov, it was moving at 93,000 mph (150,000 km/h), faster than expected for an object at its distance of roughly 2.8 AU from the Sun. Based on its blazing speed and its trajectory, which shows it delving into the inner solar system at an angle of 40° relative to the ecliptic plane on an orbit with a staggering eccentricity of 3.7, it too did not originate in our own solar system.

Unlike ‘Oumuamua, Borisov has a clear tail, marking it immediately as a comet. And it is still on its way toward the Sun, estimated to swing around perihelion December 8, 2019, at a distance of about 2 AU from our star. That means it’s going to get brighter before it gets fainter again, potentially reaching magnitude 15 by the time it passes closest to Earth on December 28. That’s a magnitude amateur scopes larger than 10 inches can achieve under excellent viewing conditions. Even after it fades from amateurs’ sight, professional observatories will be able to track Borisov through October 2020.

Meech’s team has already observed the object and estimates its size between 1.2 and 10 miles (2 and 16 km). They’ve already spotted CN gas coming off its surface, although the comet was still too faint in October 2019 to detect other gases, she says. But “with 2I, we have a really long observing period of a year,” Meech says. That will allow astronomers to explore its chemistry — unlike ‘Oumuamua — even if, she says, the comet’s gas and dust may hinder attempts to get a good handle on the shape and size of its nucleus. But ultimately, “[2I] looks like a comet, and it’s red, and it’s got CN.”

That means it looks very much like a typical solar system comet — and paints a very different picture of an interstellar traveler than ‘Oumuamua. But those differences are valuable for astronomers trying to learn more about how other solar systems form, whether they are like or unlike our own.

Regardless of how many interlopers we eventually see skimming through our solar system, ‘Oumuamua will always be the first. And although it’s left astronomers with outstanding questions, it also represents the beginning of an era in which we may finally unlock many of the mysteries behind how stars form their planets, and what happens to the pieces they lose along the way.