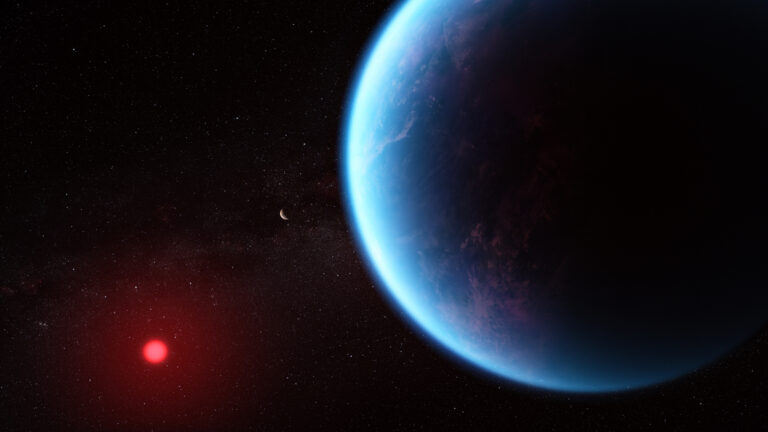

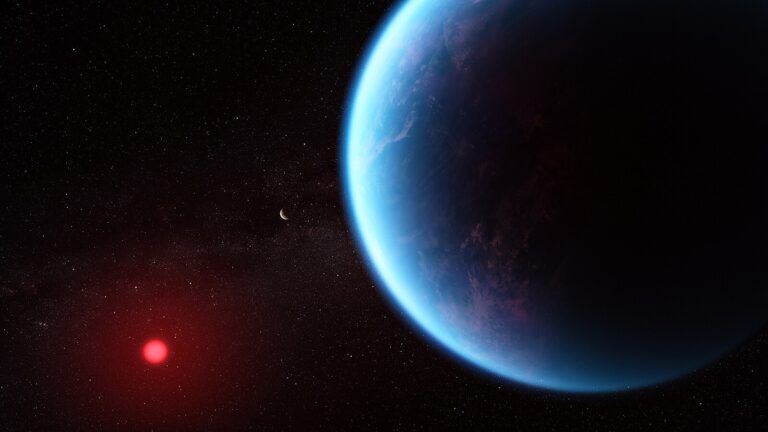

The renowned and sometimes unorthodox physicist and mathematician Freeman Dyson of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, published his ideas about this concept in 1960. He described what he considered an inevitable technological progression that ultimately would lead to a shell of such solar arrays surrounding the host star. This product of an almost unimaginable feat of engineering quickly came to be called a “Dyson sphere.”By harnessing much, most, or even all of a star’s radiation, such structures would keep most of the light from escaping. But because energy can never be destroyed, only changed to a different form, all of this civilization’s energy eventually would end up as heat.

As Dyson pointed out, humans could detect this heat emission as infrared radiation. And they also could see visible light blocked by the huge structures that nearly surround the star. (Astronomers assume, despite their name, that most Dyson spheres would not be complete shells but instead a mix of structures and voids.)That’s exactly what the new efforts to find intelligent aliens will be looking for. Vastly expanded in scope, these searches will scan the sky for the distinctive signs of Dyson spheres, both isolated ones and in collections of a million or more. At the same time, researchers will be trying to intercept communications between aliens whose level of technology and intelligence vastly outstrip our own. Using these powerful new strategies, scientists within the next couple of years may probe for signs of intelligence through orders of magnitude greater volumes of space than ever before.A whole new era of interstellar and even intergalactic espionage has begun. You can run, you aliens, but you probably can’t hide.

On the lookout for ET

Astronomer Geoffrey Marcy at the University of California, Berkeley, recently launched two different kinds of searches, each slated for an initial two-year run. In the first, he will be looking for the most direct kind of evidence of Dyson-sphere material: the blockage of all or part of a star’s light in a pattern that repeats like clockwork as the structure rotates.To find such a configuration, Marcy – the world’s most prolific planet discoverer (he and his collaborators have found about 250 so far) – and his team are developing software to sift through the catalog of data from NASA’s Kepler spacecraft. This observatory scrutinized more than 150,000 stars continuously for some four years, until a key piece of equipment failed in May and likely ended the telescope’s ability to acquire high-precision data.Kepler turned up nearly 3,000 planet candidates during its first two years of observations by searching for periodic dips in stellar light caused by an object transiting the star. Scientists initially scoured the data with algorithms designed to screen out all but the most likely planet signatures. Marcy and his team’s new strategy will look for significantly different and much broader kinds of transits.Astronomer Andrew Howard at the University of Hawaii is a co-investigator on the project. “Doing a complete Dyson sphere is the ultimate engineering tour de force,” he says, although “a rigid Dyson sphere is probably infeasible.” That’s just as well because a partial one is much easier to detect. “Kepler is good at detecting transits,” he says, including those that are much shorter, longer, or more erratic than those sought by planet hunters.The search for extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI) has reaped the rewards from decades of growing technological sophistication. Until now, however, almost all of the searches have focused on looking for aliens who were deliberately trying to get our attention. This was the low-hanging fruit, the kinds of signals that scientists could detect and distinguish most readily from a background maelstrom of noisy and unpredictable emissions.Most search strategies have concentrated on radio or laser signals that humans knew how to send (in principle, at least, if not in scale) and on technology that already existed or that we could adapt. Many of these efforts are ongoing and continue to grow more powerful and extend their reach ever deeper into our stellar neighborhood.But a whole set of new programs takes a different tack. These searches target highly advanced civilizations throughout our galaxy and beyond without assuming that they are putting any time, effort, or thought into communicating their presence. In fact, these methods should be capable of finding any such sophisticated aliens – even if they’re trying hard to make themselves inconspicuous.Such new-generation searches are predicated on the notion that any advanced technological civilization, and whatever kind of biological being is creating it, must harness energy on a vast scale and obey the laws of physics. If the aliens don’t drive themselves to extinction, the thinking goes, their civilization will keep expanding. And any such society will have an insatiable appetite for energy. Ultimately, once the extraterrestrials have exhausted the energy resources of their home planet, they will take to space and start dismantling other planets and moons to build ever-larger solar arrays capable of capturing as much of the energy produced by the local sun as possible.”If some other shaped object eclipsed its star – a big solar array [for example] – it would produce a different shaped light curve,” says Howard. To develop the techniques, the team will precisely tune their search criteria by practicing on a few stars that can be studied in detail. “The real challenge here is developing the software,” he says. “Then we’ll turn it loose. After that, it’s just computing time.” The researchers will try to look at all of the stars in Kepler’s catalog. Then, Howard says, “We’ll figure out what the oddballs are that this software finds.”Nobody else has systematically searched through this catalog for such signals. So, even if the team fails to turn up any Dyson-sphere-building civilizations in the small area Kepler monitored, it might well turn up some new and unexpected physical phenomena. Such new searches often do. Even so, Howard concedes, “We’re still just kind of scratching the surface.”

Mining the data

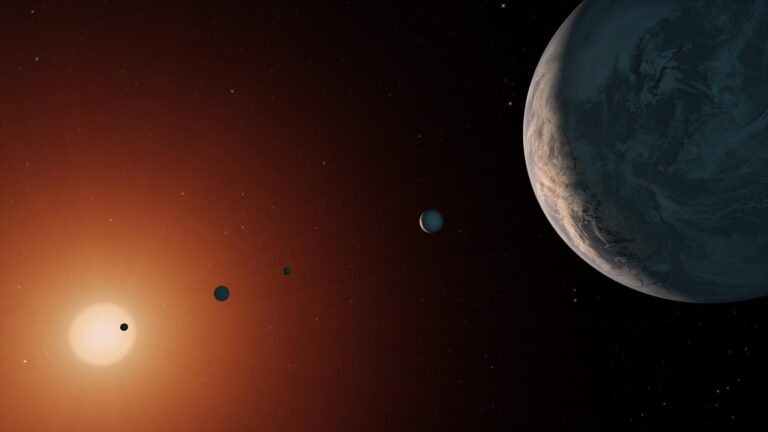

Marcy’s group is not the only one hunting through Kepler data for novel signs heralding alien engineering. Lucianne Walkowicz at Princeton University runs another such search. Her team is seeking what it calls “stellar lighthouses” and using machine-learning algorithms to find patterns in the data.”We’re looking at the data itself – how certain things group together – and looking for things that deviate,” Walkowicz says. The researchers will scour the data for both increases and decreases in light levels, which could indicate anything from laser flashes to massive structures or even partial Dyson spheres – or something as yet unthought of.”The strength of our proposal is that it doesn’t presuppose” what kinds of signals we might detect, Walkowicz says. The algorithms will be similar to those some large companies use to mine consumer data in order to target coupons for products a person might be considering. For example, just by monitoring buying patterns, she says, “They can tell when you’re pregnant.”Although the basic concept of searching astronomical data for signs of Dyson spheres is not entirely new, the tools available now make it possible to extend such searches in ways that were impossible a few years ago. “It’s the data that’s new, and the techniques that are new,” Walkowicz says.Howard says the team plans to focus special attention on a set of particularly promising targets. Kepler scientists already have discovered a few dozen stars that have more than one planet. Marcy’s team calculates the precise relative positions of the planets in these systems and then looks for instances when a line connecting two of them points toward Earth. “You can compute the times when the planets are not only aligned with each other, but also aligned with us,” says Howard. That way, if the system harbors alien beings who have colonized multiple worlds and are keeping in touch with one another, “Earth would be in the spillover region for communications between planets.”

Spheres by the millions

For several years, Carrigan also worked on a different kind of search, one that’s a bit more ambitious: looking for entire galaxies full of Dyson spheres. If Dyson-like structures surround all, or at least a significant fraction, of the stars in a galaxy, then the galaxy’s overall emission (or a sizeable portion of it) would have a strong excess of infrared radiation over visible light. He concentrated his search on elliptical galaxies. “This galactic astronomer pointed out that if you’ve seen one spiral galaxy, you’ve seen one spiral galaxy,” Carrigan says. “But if you’ve seen one elliptical, you’ve see them all. So let’s start with ellipticals.”The basic concept is that any civilization advanced enough to build a Dyson sphere in the first place will want – and even need – to expand. Such a species could propagate throughout a galaxy on a short time frame compared with the lifetime of its home galaxy. “In tens of millions of years, you can travel across a galaxy,” Carrigan says. So, in making the leap from a single sphere to a galaxy full of them, he says, “The transition can go fairly fast.”Carrigan’s initial search of galaxy data turned out to be a little more complex than he anticipated. The elliptical galaxies were a bit more diverse, he says, and while there were some interesting cases, he found no strong candidates.This is where the latest search will be picking up, using fresh data. Astronomer Jason Wright at Pennsylvania State University is running this two-part effort. “We’re going to be looking for extremely red objects,” he says. His team is scouring data from the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) satellite, which mapped the entire sky at high resolution in four different bands of infrared light. NASA is releasing the satellite data in batches, which already cover more than 500 million sources. “We’re going through that and looking for the reddest [objects],” he says.The tricky part will be ruling out galaxies that appear red simply because they lie far across the universe and their light has been highly redshifted by cosmic expansion. But those distant galaxies should have sizes and spectral signatures that would help rule them out. By finding objects that have the right signature in WISE’s four infrared bands, Wright’s team hopes to be able to home in on those that could be whole galaxies full, or at least half-full, of stars with surrounding Dyson spheres.”If every star is half-covered, or if half the stars are covered, that works out just fine,” says Wright. Like Carrigan, he’s convinced that half-full galaxies will be rare because the theoretical time to colonize an entire galaxy should be relatively short. To happen across a galaxy that’s only half-populated with Dyson-sphere builders, he says, would be like picking one human being at random out of a hundred and ending up with an infant.The second part of Wright’s efforts will be another search for Dyson spheres within the Milky Way Galaxy. The team will be looking for individual stars that appear exceptionally red. But the quest will be complicated. “We’re going to have to worry about things that are dusty” to weed out spurious cases, explains Wright. “We’re going to have to catalog where the dust is and look for the outliers.” In the end, he says, they will have a list of objects that are “redder than any natural astrophysical object.”

Are we alone?

After the two-year project and its companion searches are over, what if nothing has turned up? What if there’s no sign of either Dyson spheres or Dyson-filled galaxies?Wright says there could be a few different explanations. One obvious possibility is that we really are alone in the universe. Of course, we’ll never know this for sure because some life-bearing planets may never develop an advanced civilization.But there might be other, more life-affirming reasons. “It could be that there is life in the universe, and it didn’t end up using most of the available energy [by harnessing a whole star’s light],” says Wright. “If in a billion years we’re still around but only using about 1 percent of the Sun’s light – if that’s normal, if civilizations never use more than a small percentage of their star’s light – then we’ll never detect them.”I don’t really understand how that could be,” adds Wright, who is convinced that any technological civilization inevitably will gobble most of its star’s energy output. “But that could be, and the universe could be filled with civilizations and we won’t detect them.” Alternatively, he says, “It could be that there’s cool new physics that we haven’t discovered – ways to get rid of waste heat with neutrinos or something” that would not emit the expected infrared signal.Of course, if nothing at all shows up in any of these new or planned searches, says Wright, “The simplest explanation would be, they’re just not out there.”Richard Carrigan, a particle physicist at the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory in Batavia, Illinois, carried out some earlier searches looking for infrared excesses in the best data sets available at the time. He examined the catalog of sources compiled by the Infrared Astronomical Satellite, a spacecraft that scanned the entire sky at infrared wavelengths in 1983. He looked for stellar objects whose infrared emissions were anomalously high in relation to their visible light – just what you’d expect from a Dyson sphere.Carrigan ended up with “a handful” of interesting candidates, he says, out of the 17 anomalous stars he identified. But nothing was unusual enough to be a clear sign of some non-astrophysical phenomenon. He also tried using the Allen Telescope Array – a powerful collection of 42 radio dishes, each approximately 6 meters in diameter, dedicated to SETI projects – to follow up on some of these candidates. Carrigan wanted to see if their unusual infrared emissions correlated with any kind of unusual radio signals. “I didn’t find any candidates,” he says, though some potential targets were in the southern sky and inaccessible from the array.

Listening to their conversations

Marcy, Howard, and the rest of their team also are conducting a separate SETI project in parallel with their Kepler-based Dyson-sphere search. With this method, they hope to eavesdrop on extraterrestrials rather than look for intentional transmissions. The idea is to hunt for signals these aliens may be beaming to each other using modulated laser beams. Earth just might happen to lie along the path of these communications and intercept some of the beams.Not only are lasers the most efficient method of long-distance communications humans know of, but their beams also would have a distinctive signature – a sharp spike in frequency is characteristic of laser systems but unlike any known natural phenomenon.The technique is a new wrinkle on a strategy Harvard University physicist Paul Horowitz and his colleagues have been pursuing for some 15 years. Horowitz’s team looks for flashes of laser light, which if emitted in short pulses could outshine a Sun-like star by a thousand times in some wavelength bands – even with late-20th-century human technology.Marcy’s team uses both a spectroscope (to break the incoming light into its component wavelengths) and a photometer (which measures light intensity) to distinguish not only pulses in time but also the laser’s spectral purity. Those narrow emission peaks would provide a distinctly unnatural profile even if the light’s overall intensity is no more than that of the central star.