The isotopes of uranium are radioactive. They eventually will decay by releasing two protons and two neutrons concurrently. After this process repeats itself several times, and several neutrons in the nucleus transform into protons, the former uranium atom will turn into a lead atom, which is quite stable. This decay occurs at a predictable rate. So, if we know how much uranium is present now in a particular star, how much was there when an ancient supernova (probably) produced it, and what this decay rate is, we can calculate the age of that uranium. This is one method that astronomers use to measure the ages of stars.

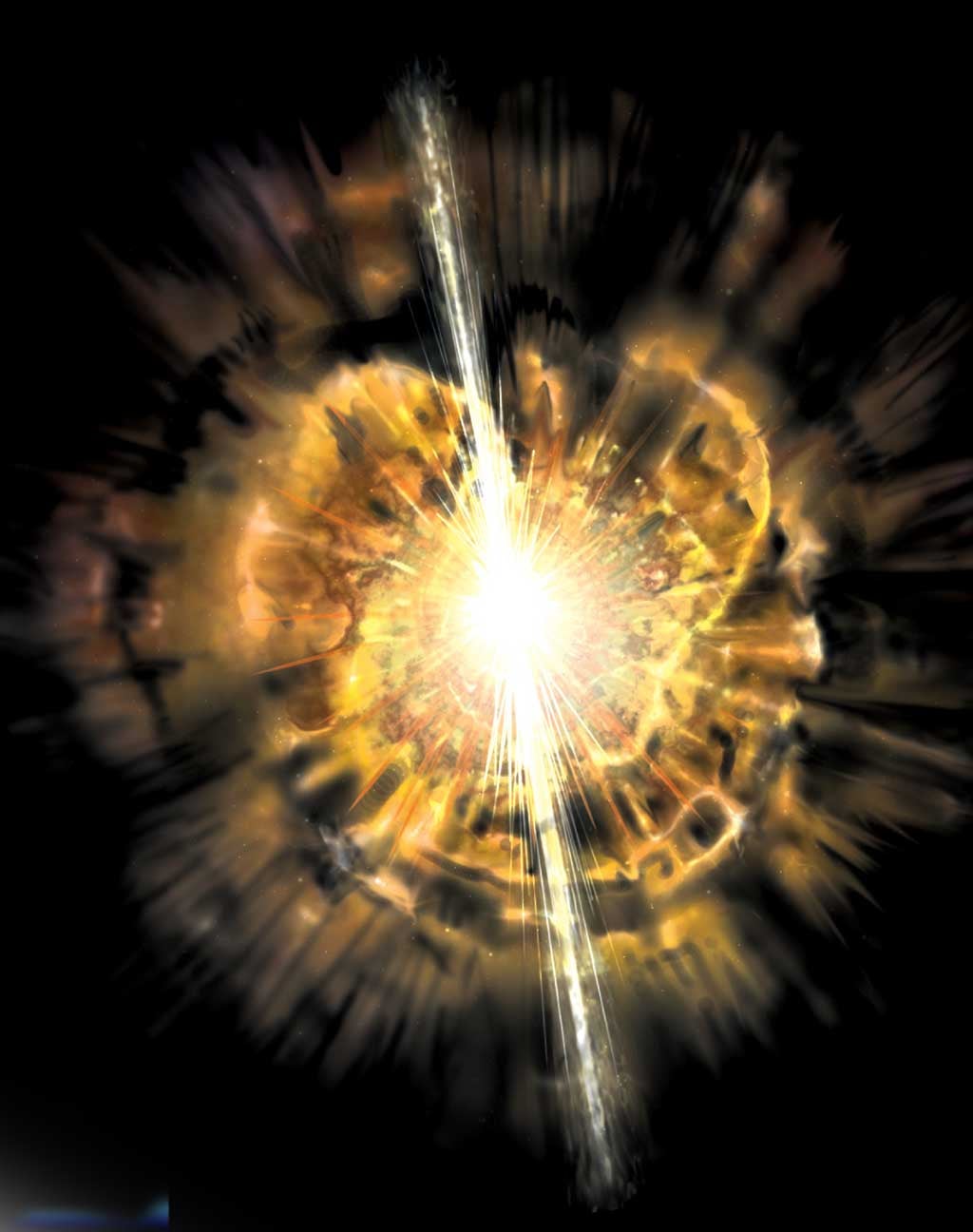

Certain kinds of supernovae, the violent deaths of massive stars, produce uranium. This uranium then likely is swept up into the next generation of stars; we still see some of the second generation today. The fact that we find uranium and other heavy elements in these ancient stars reveals an unexpected result: Somehow, the earliest generations of supernovae managed to produce elements all across the periodic table. The process for creating the heavy elements was not gradual at all.

Carnegie Observatories, Pasadena, California