Key Takeaways:

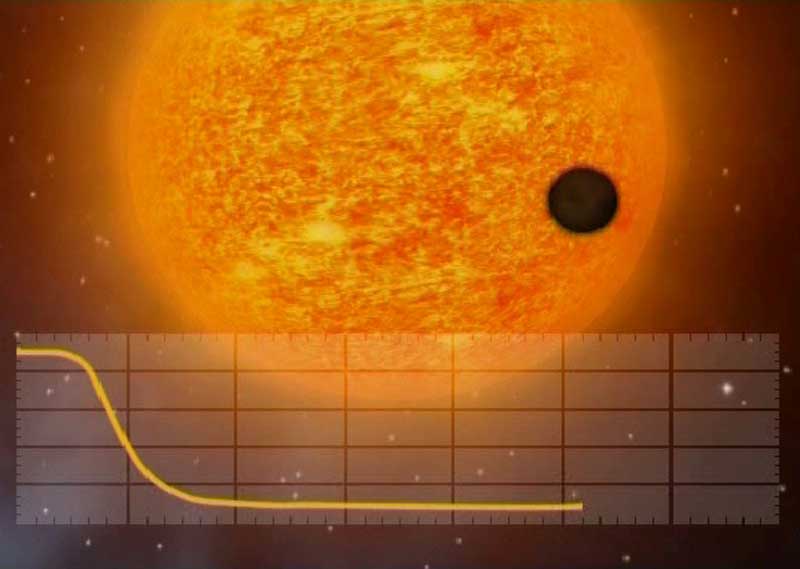

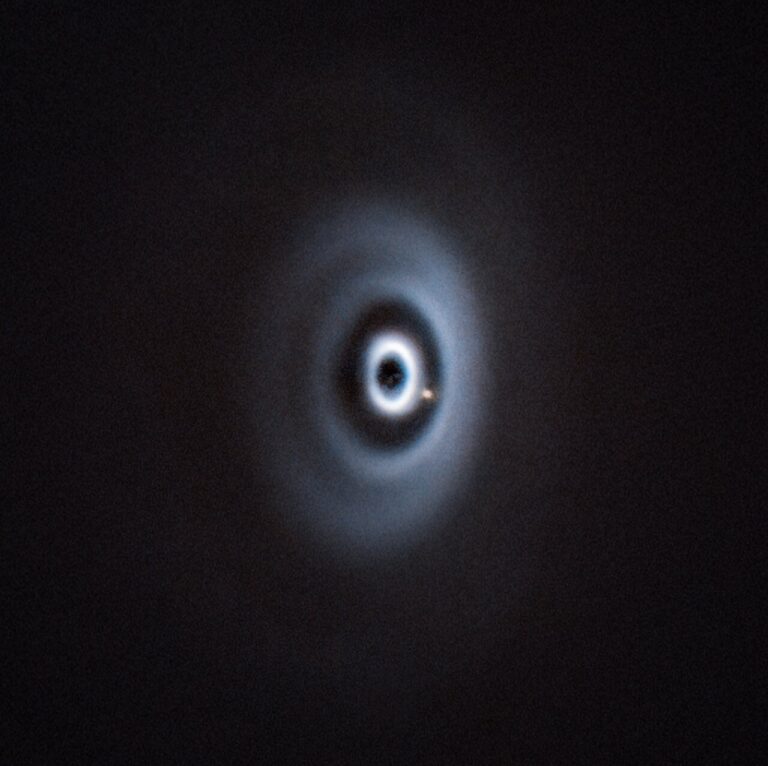

- The probability of observing a planetary transit depends on both the star's diameter (D) and the planet's semi-major axis (a), approximated by the ratio D/(2a).

- For planets with short orbital periods (a few days), the transit probability can be significantly higher (10-20% or more).

- For Earth-like planets at 1 AU, the transit probability is considerably lower, approximately 0.47%.

- The overall range of transit probability for Sun-like stars is estimated to be roughly 0.5% to 15%, with planets in habitable zones exhibiting a probability closer to 0.5%.

So, there is no single percentage to answer the question because it depends on how big the orbit is. For a planet whose orbital period is just a few days, the probability could be 10 to 20 percent or more. But for an Earth-like world at 1 astronomical unit (our planet’s distance from our star) with a period of 365 days, the probability is only 0.47 percent. Thus, the percentage ranges, roughly, from 0.5 percent to 15 percent for a star like the Sun. Because NASA’s Kepler mission team is most interested in planets within their stars’ habitable zones — where liquid water might exist on these worlds’ surfaces — the probability is close to that half-percent mark.

Another important aspect to keep in mind: Transits of planets in large orbits are rare events. You get just one transit per year of a planet in an Earth-like orbit. So, not only is the probability low of ever seeing a transit, but for the vast majority of the time the planet will not be transiting. You have to observe for many years to know for sure.

San Diego State University