Key Takeaways:

The most common way to produce entangled states — where two particles remain mysteriously correlated regardless of distance — is when particles or fields interact or are created together. Since we believe quantum mechanics would hold during inflation, entanglement between different degrees of freedom in these exotic fields would be a natural outcome. It is an open question whether inflationary-era entanglement could survive the chaotic process of reheating.

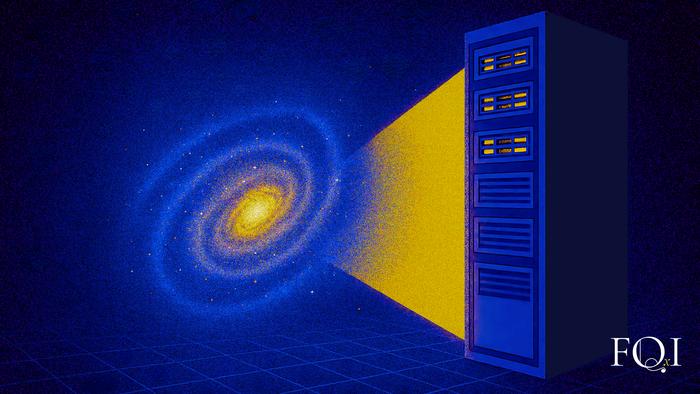

Purely considering causality, inflation makes regions of space separate faster than the speed of light (this is allowed in general relativity). So today, regions once in causal contact during inflation are now out of causal contact, beyond each other’s so-called cosmic horizons.

The main question is whether any entanglement set up during inflation could survive and persist to somehow produce observable effects today. The answer is that we don’t know. We probably require a full theory of quantum gravity to even formulate such a question precisely. But even without knowing the details, cosmic scale tests of quantum mechanics are probably the best way to look for any strange effects. It certainly would be wonderful if the early universe left us such clues because it could let us use local measurements of space-time to test questions about parts of the universe that seem inaccessible in principle.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge