That is not the end of the story. The outer layers of the star feel less gravitational pull as they expand, making it easier for material to escape. If the star keeps expanding while maintaining constant surface speeds, eventually the material at the equator will fly off. We think some stars might be born spinning so fast that they do reach “breakup” during their hydrogen-burning lifetime.

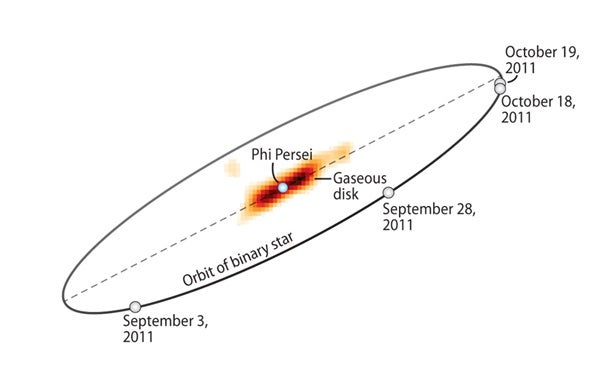

Possible evidence for this picture comes in the form of hot, gaseous disks seen around some hot stars — the so-called “Be” stars, where B refers to the temperature spectral type and little “e” means that the star shows emission lines. We think gas at the equator of a fast rotating star gets nudged out of the photosphere and into orbit, pushing on material that left earlier until a little disk forms. The accompanying photo illustration is a real infrared image of such a gaseous disk we recently captured using the CHARA Interferometer on Mount Wilson. Occasionally amateur astronomers discover normal B stars that all of sudden become Be stars. But how can the gas disk appear so suddenly, within a few weeks? We someday hope to take a picture of this happening in real time with CHARA to find out.

University of Michigan