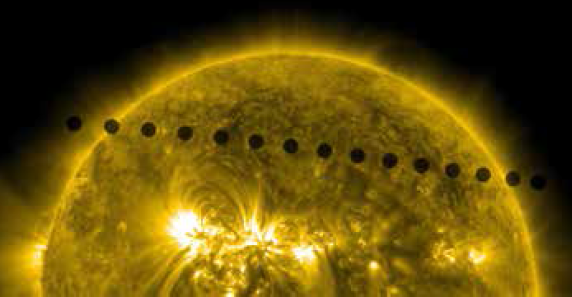

As a result of its orbital tilt, Venus can transit only when it is near one of two points in its orbit where it crosses Earth’s orbital plane. Due to the ratio of Earth’s orbital period compared with Venus’ period, transits come in pairs separated by eight years and then long gaps on the order of 100 years.

Now, imagine that Earth is stationary where the plane of its orbit intersects with Venus’ orbital plane. We would get a transit once every Venus orbit (225 days). This is essentially the situation we have with exoplanets. We are so far away from those stars that Earth’s orbital motion is insignificant. This means that the only thing controlling whether a transit occurs is the orbital inclination of the transiting system with respect to our line of sight. We assume these orbits are randomly oriented in the sky, and from that, we can statistically derive the number of planets total in a given population of stars, based on the number of transits that we observe.

We can answer your second question by doing a back-of-the-envelope calculation using planets discovered by a different method called radial velocity (RV, which identifies planets by their gravitational tug on a star), and then asking how many of them transit. About 10 out of 481 RV planets transit, which is in line with what one would expect from random orientations, based on average values for the sizes of stars and the distance of exoplanets from them.

Nathan De Lee

Assistant Professor, Department of Physics,

Geology and Engineering Tech,

Northern Kentucky University,

Highland Heights, Kentucky