Key Takeaways:

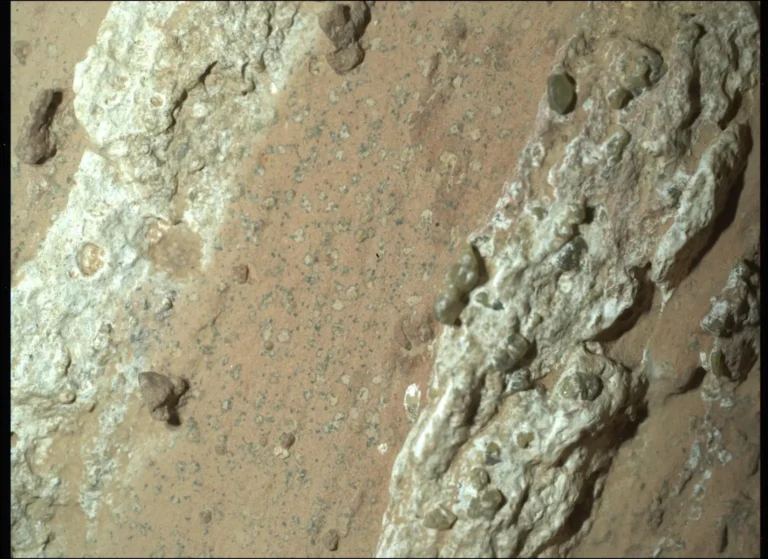

When viewed edge-on, such as from our solar system’s position within the galaxy, the disk of the Milky Way does indeed appear as a straight line across the sky. The arc you reference in many photographs is an artifact arising from the way these images are processed afterward by the photographer.

You simply cannot see the entire sky at once, nor can you photograph it in one shot with a standard lens. Most full-sky photographs, including the one you note, are panoramas made up of several images stitched together. Each individual image captures only a portion of the sky (and landscape), and in each single shot, the Milky Way does appear straight. But when these images are stitched together, the photographer must introduce distortion to turn them into a single square or rectangular photo. This is because the final photo is a flat projection of a curved sphere, which introduces distortion that ultimately makes the Milky Way appear curved in order to make the horizon appear flat.

Alternatively, some images are taken with a fisheye lens, which itself produces distortion in order to image an extremely wide field in one shot.

There is one caveat: The Milky Way appears straightest when it is most directly overhead. Astronomy senior editor Rich Talcott points out, “The plane of the Milky Way projects as a great circle onto the celestial sphere (as does the ecliptic, which we are also in). So both the Milky Way and the ecliptic appear as large circles in the sky (which, if they happen to pass overhead, will appear as straight lines). But if the circles reach a peak altitude of only, say, 30°, they’re going to look like arcs to the naked eye.”

Alison Klesman

Associate Editor