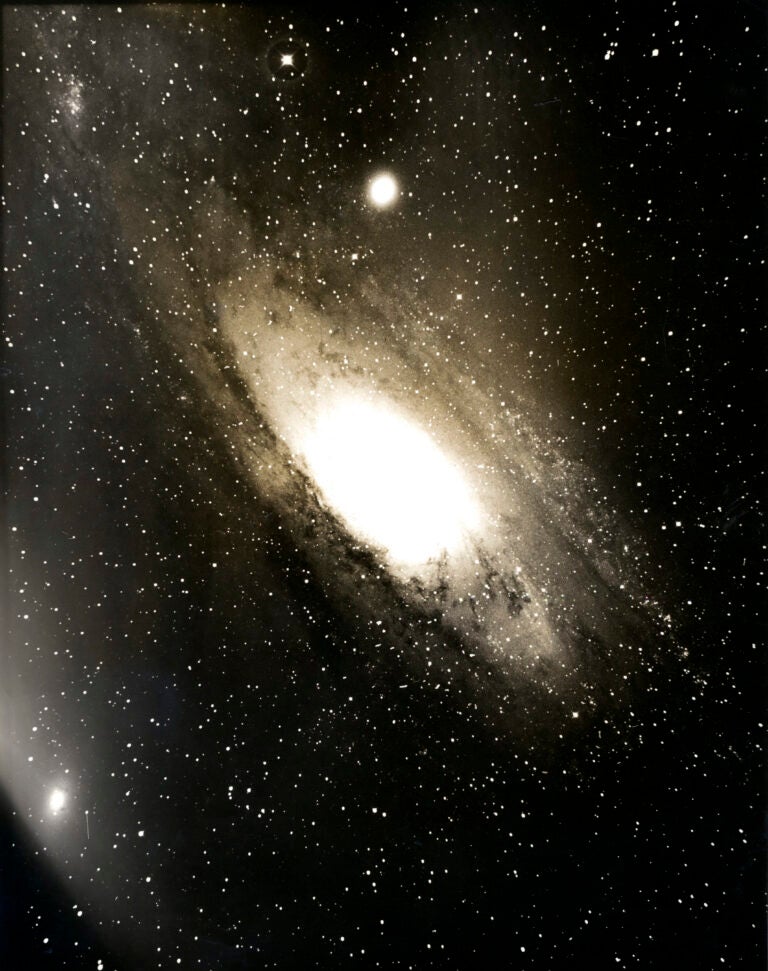

Since the early 1900s, it has been known that M31 is moving toward the Milky Way. Advanced technology has helped astronomers pin down the speed of M31 to nearly 250,000 mph (402,336 km/h). However, until 2012, the transverse motion of M31, or its proper motion across the sky as a function of time, was not yet measured, and the net direction of M31’s velocity toward the Milky Way was also unknown. In other words, it was unclear whether the Milky Way and M31 would collide head on or just miss each other.

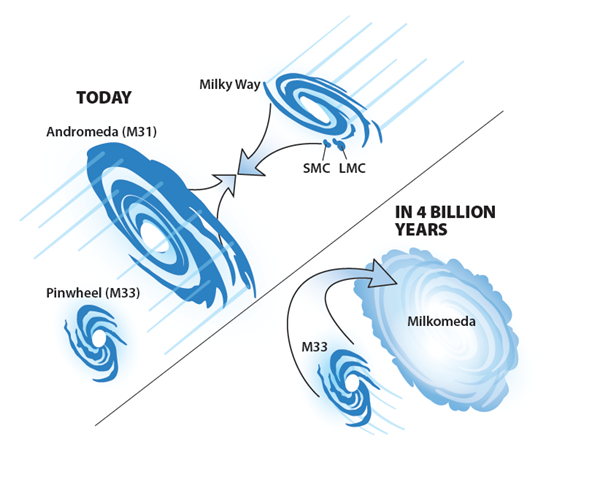

In 2012, a team based at the Space Telescope Science Institute published a study in which they used the Hubble Space Telescope to measure the proper motion of M31. They found that it is primarily moving in the direction along the line of sight between M31 and our vantage point near the Milky Way’s center (i.e., the transverse motion of M31 is low), meaning that the Milky Way and M31 are on a nearly head-on collision course. Based on this work, the team concluded that the first collision will take place about 4 billion years from now, and that multiple collisions occurring between 4 billion and 6 billion years from now are required for the galaxies to completely merge into one final galaxy. The team also concluded that M33 will miss the initial collision between the Milky Way and M31; however, it may eventually join and later merge with the combined Milky Way-M31 remnant galaxy. There is also a chance it will collide with the Milky Way prior to the Milky Way and M31 merging into one another.

In more recent work, the same team (of which I am now a part) used data from the Gaia spacecraft to remeasure the proper motions (and therefore the velocities) of both M31 and M33. We found that the Milky Way and M31 are still destined for a head-on collision 4.5 billion years from now. Including the gravitational influence of M33 and the LMC, however, causes a delay of about 1 billion years, and the first collision between the Milky Way and M31 occurs 5.5 billion years from now. The uncertainties on the galaxies’ velocities from Gaia are large, so it is difficult to narrow down M33’s fate solely based on Gaia data. These uncertainties will be significantly reduced by the end of the mission, at which point M33’s fate can be determined more confidently.

Ekta Patel

National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellow,

Department of Astronomy and Steward Observatory,

University of Arizona, Tucson