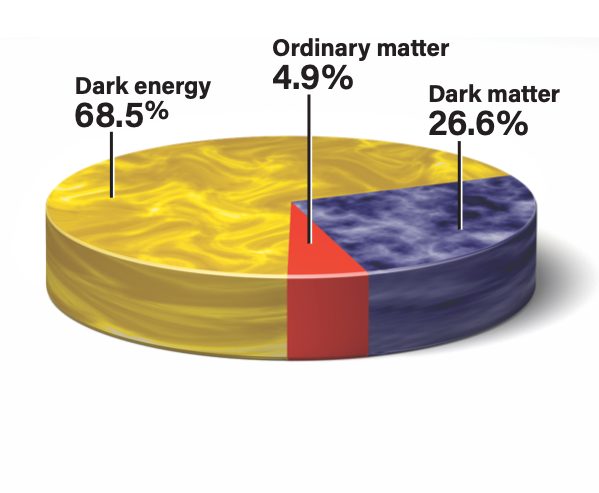

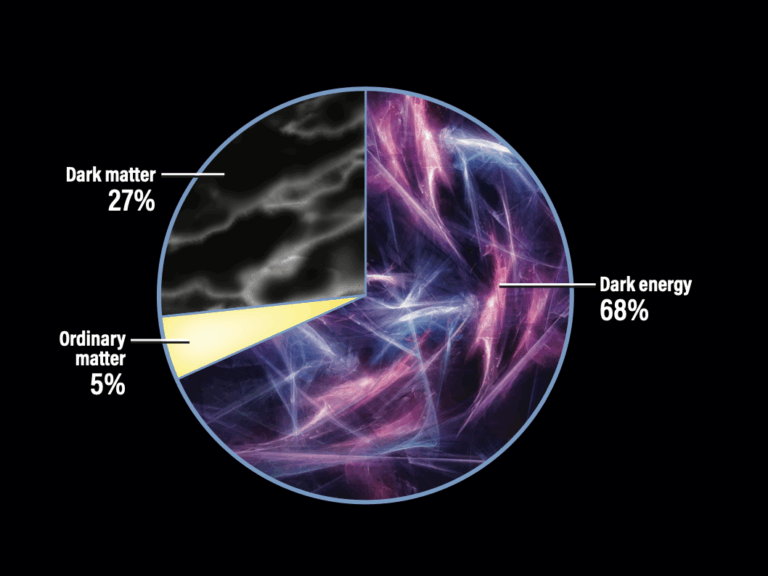

Q: If 85 percent of the mass in the universe is dark matter, why doesn’t it obscure light from distant objects? How could this material not scatter light?

A: Dark matter is called “dark” because it doesn’t give off or interact with light — including through scattering. It is simply the nature of dark matter and why it is so difficult to study. But some models of dark matter state that on rare occasions, dark matter particles could be capable of interacting with normal matter, including by scattering light.

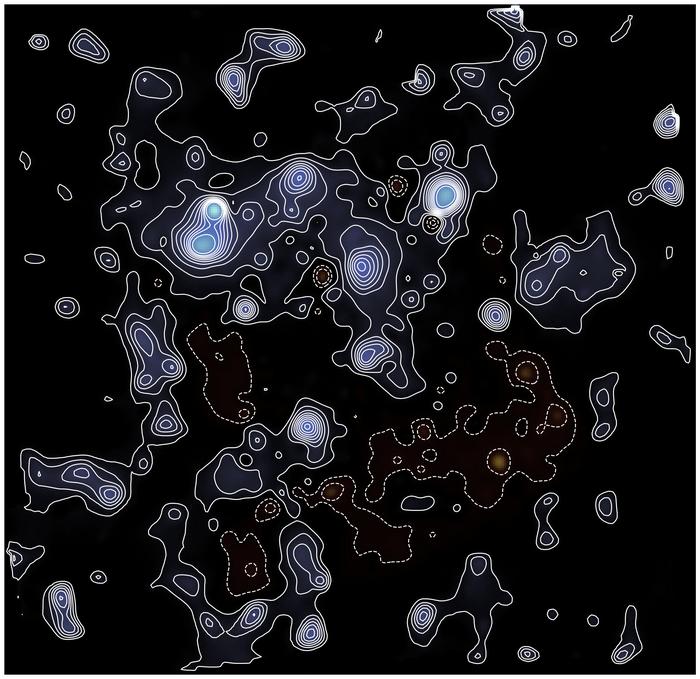

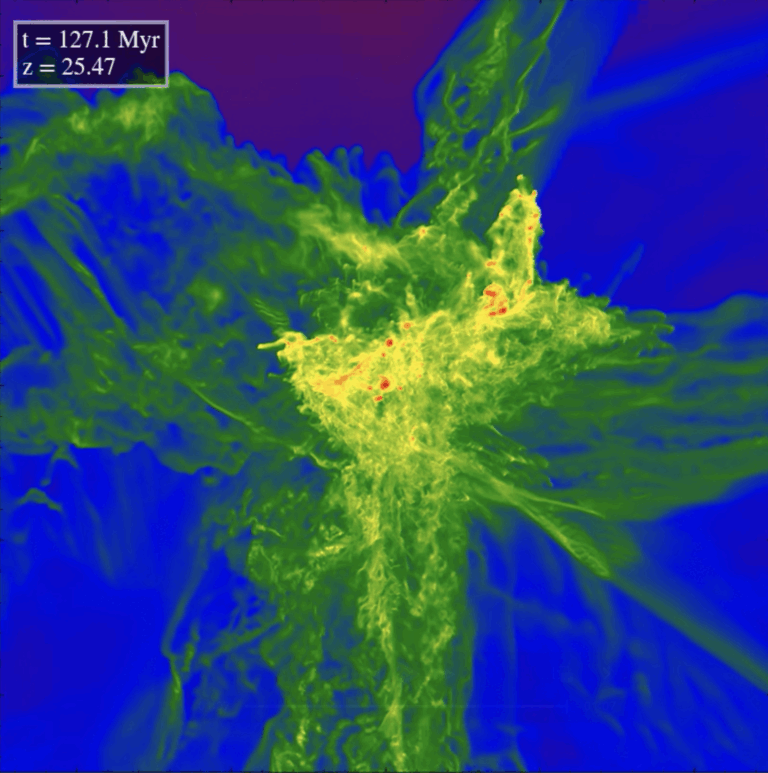

Astronomers know that dark matter is largely situated in spherical halos that enclose galaxies (more on that in a moment). If the dark matter in that halo scatters the galaxy’s starlight, even rarely, it could create a dim glow, like the halo of a light seen in thick fog. Researchers have searched for that glow but so far have not seen it. One possibility is that the glow is difficult to see at optical wavelengths, which is where past studies have focused. Scientists think such a glow, if it exists, might be easier to detect at longer infrared wavelengths, but no studies with the sensitivity needed to see this faint scattered light have been performed yet.

However, dark matter does have mass and its gravity can influence matter and light. So, dark matter does contribute to a phenomenon called gravitational lensing, in which a galaxy’s mass — including both its normal and dark matter — causes the space-time around it to curve. As light from an object in the background, such as a more distant galaxy, encounters this curved space-time, it appears to bend, which distorts and can even multiply the image of the background object. Astronomers do observe this effect, and by comparing the amount of gravity necessary to do the bending with the amount of visible matter, they have used it to confirm that galaxies are enshrouded in massive halos of dark matter.