Q: When you write about “super-Earth” exoplanets, are you ocmparing the mass of Earth as it is now, or Earth before the Moon was formed? I have read several articles on what Earth would be like without the Moon. Would this affect the definition of super-Earth planets?

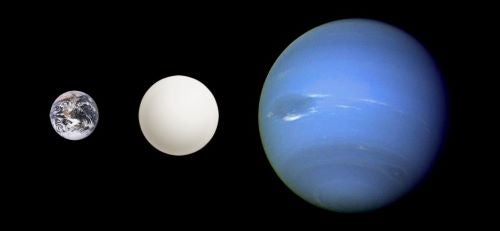

A:Super-Earths are rocky exoplanets with masses greater than Earth’s. But, in fact, there is no firm, agreed-upon definition for the mass range of these planets. Most studies consider planets with masses between about one and 10 times that of Earth a super-Earth. (However, as noted above, this number can vary. Some studies consider slightly more mass — two to three times Earth’s mass — as the lower limit, while others

consider planets as massive as Uranus — about 14.5 times Earth’s mass — super-Earths as well. It’s confusing!)

The leading theory for the formation of the Moon, the Giant Impact Hypothesis, states that a Mars-sized object, called Theia, collided with Earth to create the Moon. The mass of Earth is about 1.32 x 1025 pounds (5.97 x 1024 kilograms). The mass of the Moon is about 0.016 x 1025 pounds (0.073 x 1024 kg), or roughly 1.2 percent Earth’s mass. For added reference, the mass of Mars (and, thus, Theia) is about 0.14 x 1025 pounds (0.642 x 1024 kg), or just under 11 percent Earth’s mass. Both the masses of Mars and the Moon are incredibly small compared with Earth. So, even if you added the entire mass of the Moon back to Earth, our planet would only grow 1.2 percent more massive, or about 1.01 times its current mass. Additionally, this might be an overestimate, as not all the material in the Moon likely came from Earth, but some also may have come from Theia as well.

Thus, if we considered a “pre-Moon Earth” as the definition for the mass of Earth, we still wouldn’t really need to adjust the definition of super-Earths. Because the current definition of a super-Earth is somewhat arbitrary, I think that deciding on a universal definition would likely be the best way to make sure everyone’s talking about the same type of planet when they say “super-Earth.”