Key Takeaways:

Science journalists are confronting an odd new trustworthiness challenge. I’m not too worried about how it affects this magazine’s readers, who are mostly sky-savvy. But as astronomy editor of The Old Farmer’s Almanac for more than a quarter-century, I’ve watched with growing discomfort as its million general readers acquired strange, new notions about the cosmos.

Bringing the universe to your door. We’re excited to announce Astronomy magazine’s new Space and Beyond subscription box – a quarterly adventure, curated with an astronomy-themed collection in every box. Learn More >>.

Bringing the universe to your door. We’re excited to announce Astronomy magazine’s new Space and Beyond subscription box – a quarterly adventure, curated with an astronomy-themed collection in every box. Learn More >>.

One example: the Super Moon business. Astronomers have a perfectly fine word for when the Moon comes close: perigee. For centuries, the published lunar perigee date mostly elicited yawns. But when the term Super Moon caught on a few years ago and the mass media ran headlines like, “Don’t miss tonight’s Super Moon!,” confusion arose.The main problem is that a perigee Full Moon looks just like any other Full Moon, whereas “super” suggests something very special is afoot. Photographers soon obliged by publishing photoshopped images of an unnaturally huge Moon,and the highway to hype was now open to traffic.If we want astronomy to catch on and grow, we do want to stir up excitement. But we also mustn’t oversell celestial events that we know will fall far short of what’s promoted. It raises a simple issue: Does a term like Super Moon do more harm or more good?When I took over the Almanac’s pages long ago, I decided never to list penumbral lunar eclipses or minor meteor showers happening near Full Moon. Yet this past April, Earth and Sky – which I normally consider an excellent radio show – urged listeners to go out to watch a skimpy Lyrid meteor shower during a very bright Moon. I knew observers would be lucky to catch one or two meteors even if they stared for half an hour. Such overselling is exactly the kind of thing that turns people off from astronomy.Another concern is how pop culture perception often gets set in stone. For example, until the 1950s hit “Rock Around the Clock,” the public had correctly pronounced Comet P1 “HAL-ee’s comet.” But Bill Haley and His Comets established a pronunciation – HAY-lee – that has become permanent even though it’s wrong.Another example: If you ask people the first words spoken from the Moon, they’ll invariably mention Neil Armstrong’s “one small step” line. Actually, the first lunar words were, “OK, engine stop.” Soon after came, “Houston, Tranquillity Base here. The Eagle has landed!”

Only seven hours later did Armstrong say those famous words. Maybe you’d argue that those alone should count because he was then standing on the surface. But that’s not how life works. When you land at JFK and the plane’s crew says, “Welcome to New York,” no one thinks, “I’m not in New York because I’m still on the plane.” Similarly, as soon as the lunar module landed, the astronauts were on the Moon.You could argue this either way; my point is merely that the media-declared reality became the sole permanent truth. Commentators had speculated for days what Armstrong would choose to say when he stepped out, so only his out-the-hatch words were catnip to the press corps when the time came.

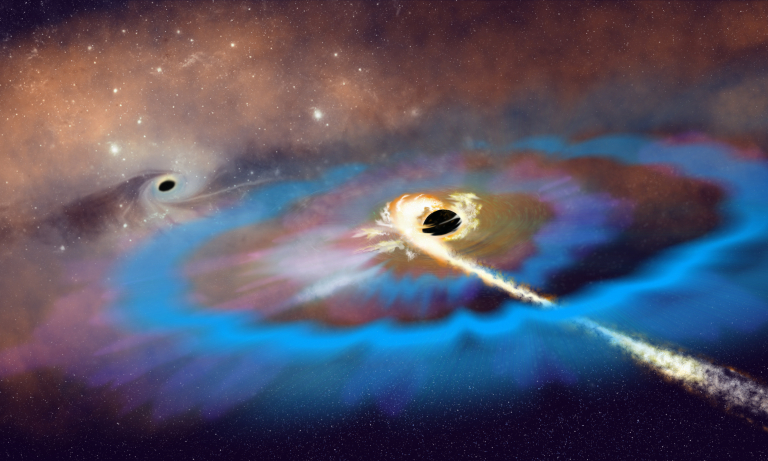

Such media-driven astro-facts still happen. Remember earlier this year when the press ran the first image of a black hole? Well, that black circular glob was actually not the black hole. It was a false-color depiction of an inky area 100 times larger than the black hole: the zone where background radio waves had been disturbed by the black hole’s presence. But even if incorrect, once this “fact” (and others like it) gains enough repetitions, it becomes our permanent model of the cosmos – which is why the vast majority of people think orbiting astronauts can see the Great Wall of China unaided or believe that births and crimes increase around the time of the Full Moon. It’s why people think professional astronomers physically look through telescopes, believe radio telescopes capture sounds, or think the Moon has a permanent dark side. Fitting into vox pop reality is probably why Alex Trebek calls our second-to-last planet “yur-AY-nus” on Jeopardy!, even though he’s normally a stickler for pronunciation.

Science programs habitually repeat the silly claim that astronauts have “escaped Earth’s gravity,” even though gravity at the International Space Station is just a barely noticeable 10 percent weaker than in the Mall of America. Few explain that the floating is solely due to the crew being in free fall.At risk of sounding like a curmudgeon, it’s weird to watch our beloved astronomy get reimagined, with the hyped version permanently established as the sole truth. But at heart, this is about trustworthiness. Which brings the issue back to whether we should ever use “Super Moon” on these pages. What do you think: Would doing so be current and colloquial, or selling out to astro-hype?