The best window of opportunity to capture the Pup is around the time of apastron (the point in its orbit farthest from Sirius). This position occurs just once every half century. I blew my chance when the two were at their greatest separation in the mid-1970s, and who knows where I’ll be for the next one?

The current window recently opened up when the separation between A and B reached 10″. The two will lie at least this far apart for the next 20 years. A two-decade window sounds like an ample amount of time, but it isn’t, as I’ll explain.

How do we go about capturing it? Here’s my strategy. First, I choose at least a 6-inch telescope and an eyepiece that magnifies at least 250x.

Your telescope and eyepiece must be of high quality and have had ample time to adjust to the outside temperature.

Because I live at a middle latitude and Sirius lies well below the celestial equator (at declination –16°43′), I wait until it’s at its highest point above the southern horizon. To test the waters, I’ll try splitting nearby Rigel (Beta [β] Orionis), another unequal pair (magnitudes 0.3 and 6.8, a 400-fold difference in brightness) whose 9″ separation is similar to the gap between Sirius A and B. If I can’t resolve Rigel easily, there’s no sense trying to tackle Sirius.

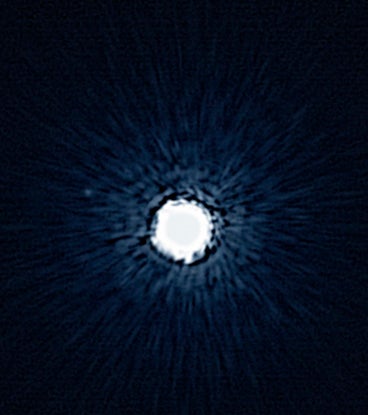

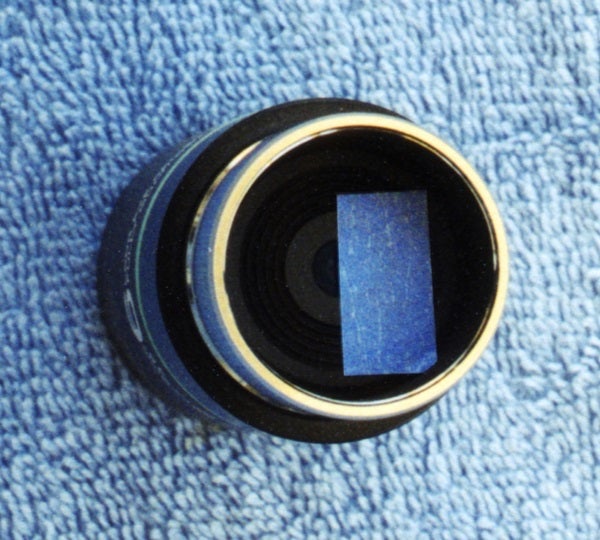

If the night is great but all my attempts fail, I’ll try two tricks of the trade used by experienced double star observers to ferret a faint companion out of the glare of a brilliant primary. One is using a hexagonal aperture mask to convert the bright star’s image into a six-spiked pattern. The dim partner may then appear between spikes. The other is to use an eyepiece with an occulting bar to cover the bright star, reducing its glare.

Speaking of bucket lists, I highly recommend Michael E. Bakich’s 1,001 Celestial Wonders to See Before You Die (Springer, 2010). This rundown of the finest deep-sky objects is guaranteed to keep you busy until you (ahem) die. Sirius is his sixth entry. Bakich notes that the Pup will widen to a separation of 11″ in 2025, after which it will begin its slow return to the glare of Sirius. It’s a deadline I hope to beat!

Questions, comments, or suggestions? Email me at gchaple@hotmail.com. Next month: My double star observer’s answer to the old Messier Marathon. Clear Skies!