Key Takeaways:

- The 1920 Shapley-Curtis debate concerned the scale of the universe, with Curtis correctly proposing a universe composed of many galaxies ("island universes"), while Shapley correctly posited the Sun's location near the edge of the Milky Way.

- A similar debate in 1996, involving van den Bergh and Tammann, focused on the Hubble constant, with differing values leading to contrasting conclusions about the universe's age and size.

- Observations using modern telescopes reveal galaxies more than 13 billion light-years away, suggesting a visible universe with a diameter of at least 26 billion light-years.

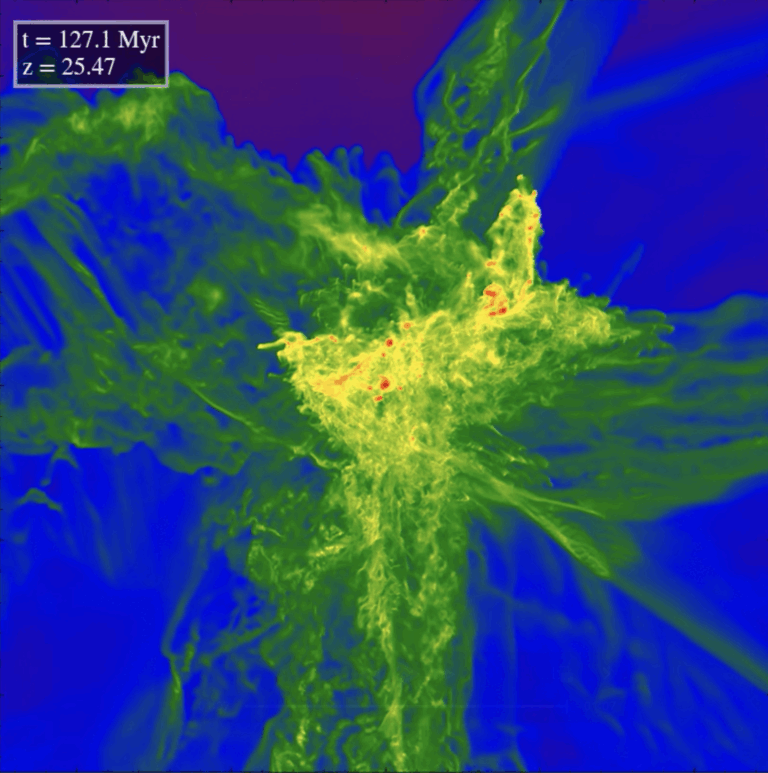

- The inflation hypothesis proposes a period of rapid expansion in the early universe, potentially implying a much larger universe, possibly including other universes beyond our observable horizon.

In this discussion, which preceded Edwin Hubble’s discovery of the nature of galaxies by just a few years, Curtis argued that the cosmos consists of many separate “island universes,” claiming that the so-called spiral nebulae were distant systems of stars outside our Milky Way. Meanwhile, Shapley argued that spiral nebulae were merely gas clouds in the Milky Way. Shapley further placed the Sun toward the edge of our galaxy — which, in his view, was the entire universe — whereas Curtis believed the Sun to be near the galaxy’s center. Curtis was right about the large size of the universe but wrong about the Sun’s place within it. On the other hand, Shapley was wrong about the small size of the universe but right about the Sun’s location within it.

Bringing the universe to your door. We’re excited to announce Astronomy magazine’s new Space and Beyond subscription box – a quarterly adventure, curated with an astronomy-themed collection in every box. Learn More >>.

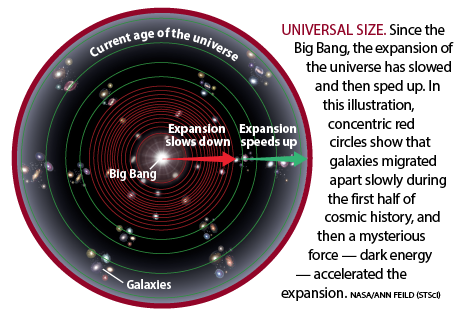

With the advent of many extragalactic distance measurements and two camps arguing for different results on the critical number called the Hubble constant — the expansion rate of the universe — astronomers staged a second great debate in 1996. The age and size of the universe are, of course, interrelated, and both depend critically on the Hubble constant.

As was the case with Shapley and Curtis, the antagonists van den Bergh and Tammann each provided crisp, clear-cut arguments and data supporting his side, and neither succeeded in convincing astronomers from the other camp. As yet, astronomers are limited by both assumptions and a lack of adequate data to agree on the cosmic distance scale.

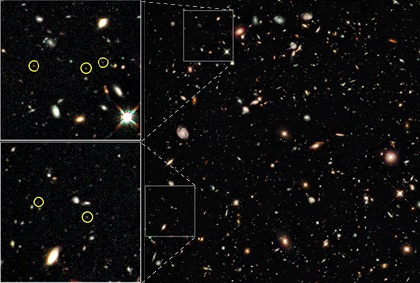

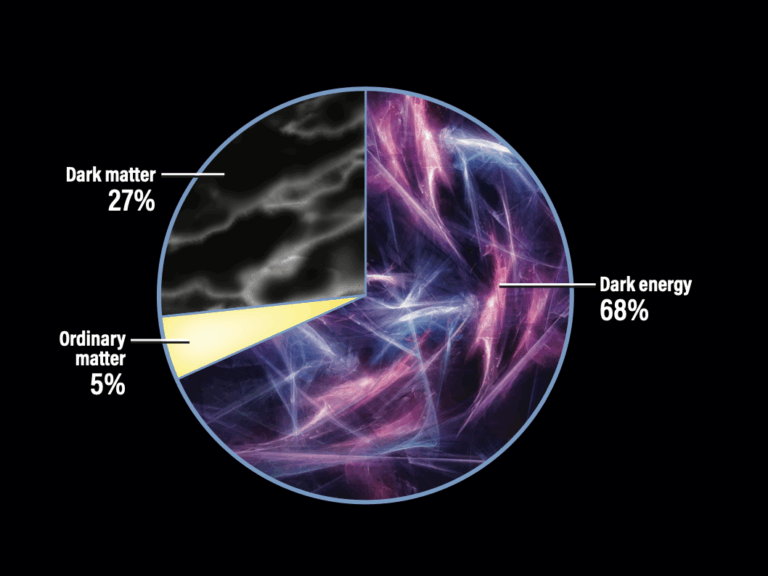

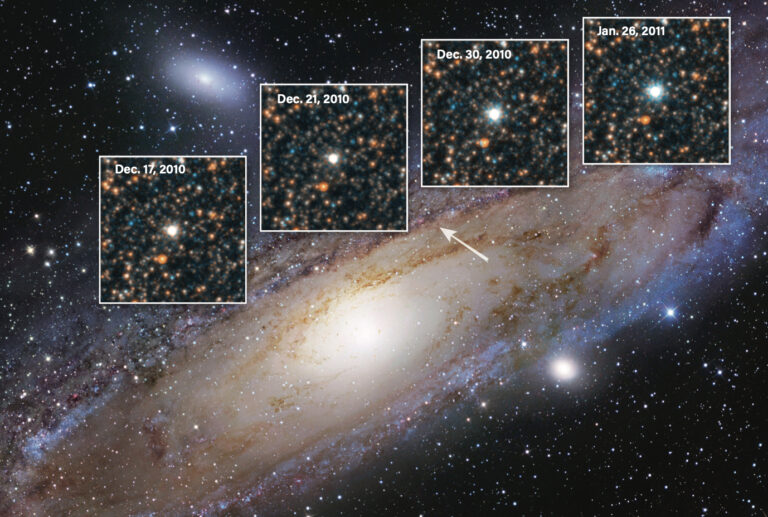

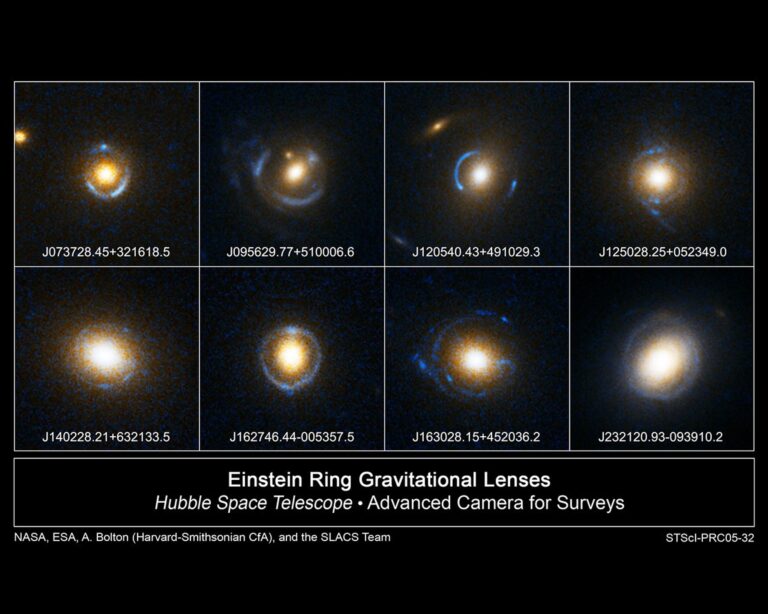

Despite this, astronomers can still set some limits on what must be true based on the observations they have collected and refined over the past century. Using today’s most powerful telescopes, astronomers see galaxies located over 13 billion light-years from Earth. (A light-year equals about 6 trillion miles, or 10 trillion kilometers.) Since they see these distant galaxies in all directions, the current “horizon” of visibility is at least 26 billion light-years in diameter.

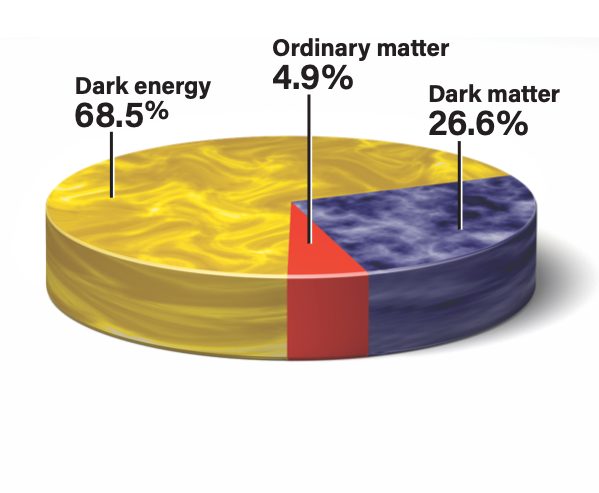

Here’s where it gets weird: If inflation happened, then it may have occurred in many places (perhaps an infinite number) beyond the visible horizon and the limits of the space-time continuum we are familiar with. If this is so, then other universes might exist beyond our ability to detect them. Science begs off this question, as by definition science is about creating and experimenting with testable ideas. For now, it’s wondrous enough to know we live in a universe that’s at least 550 billion trillion miles across, and it may be much bigger than that