For more than 30 years, astronomers have considered an intriguing question: What happens when two black holes meet? Inside a galaxy, black holes that formed from dead massive stars sometimes encounter each other, especially in double or multiple star systems. And for years, though no one had witnessed such a collision take place, the subject remained a hot topic of theoretical astrophysics.

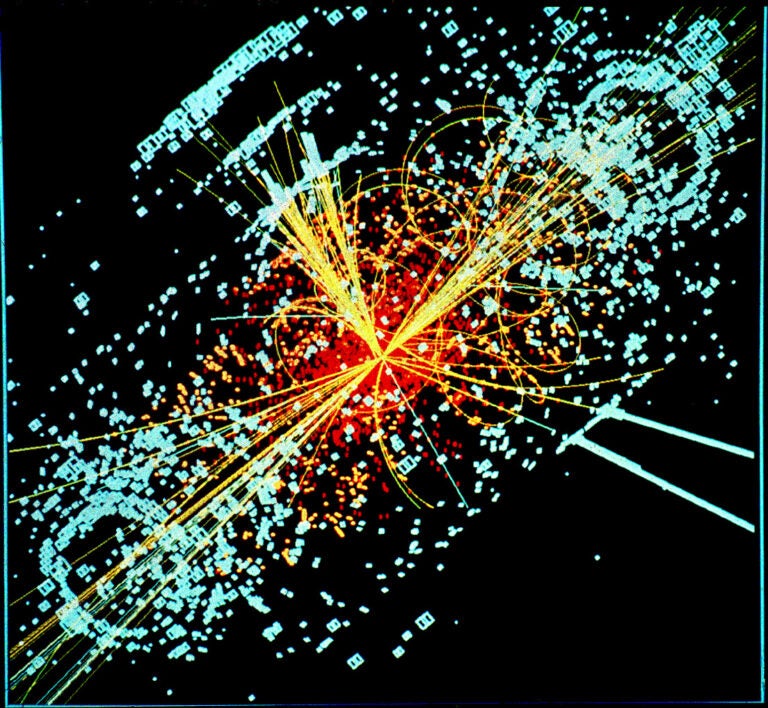

Studying the possibilities took a big step forward in 2004 when a team of astronomers — Marc Favata of Cornell University, Scott Hughes of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Daniel Holz of the University of Chicago — authored a study that appeared in The Astrophysical Journal Letters; this kicked off a number of other studies to create a burgeoning field.

Bringing the universe to your door. We’re excited to announce Astronomy magazine’s new Space and Beyond subscription box – a quarterly adventure, curated with an astronomy-themed collection in every box. Learn More >>.

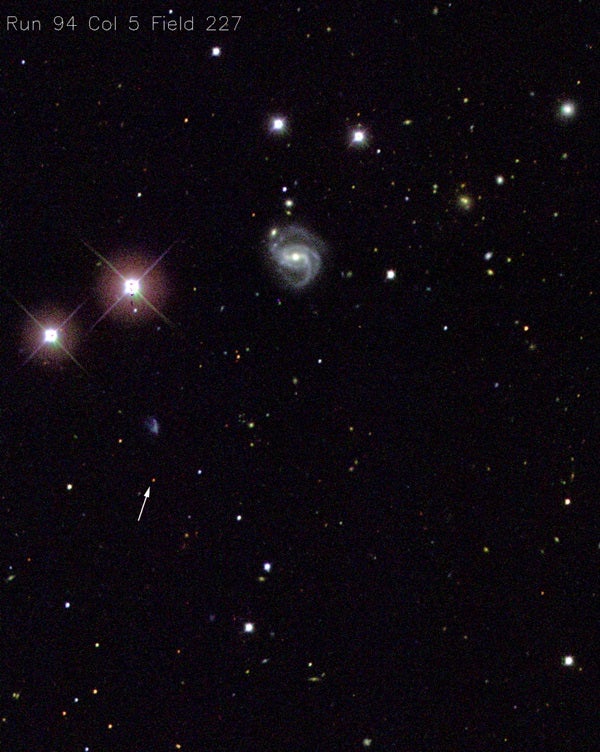

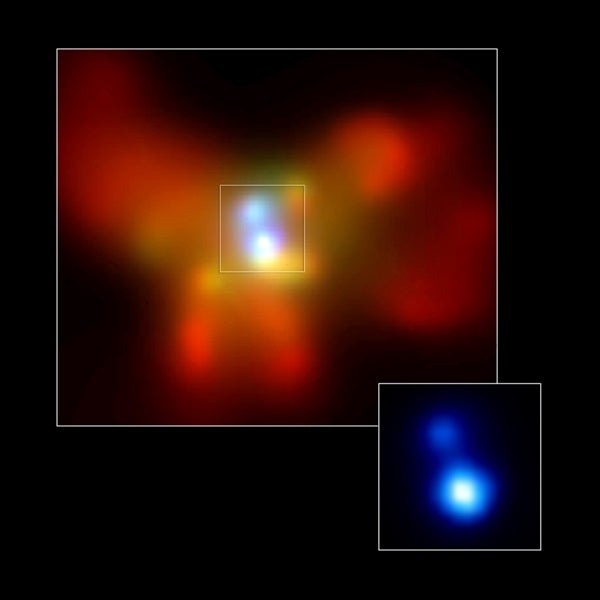

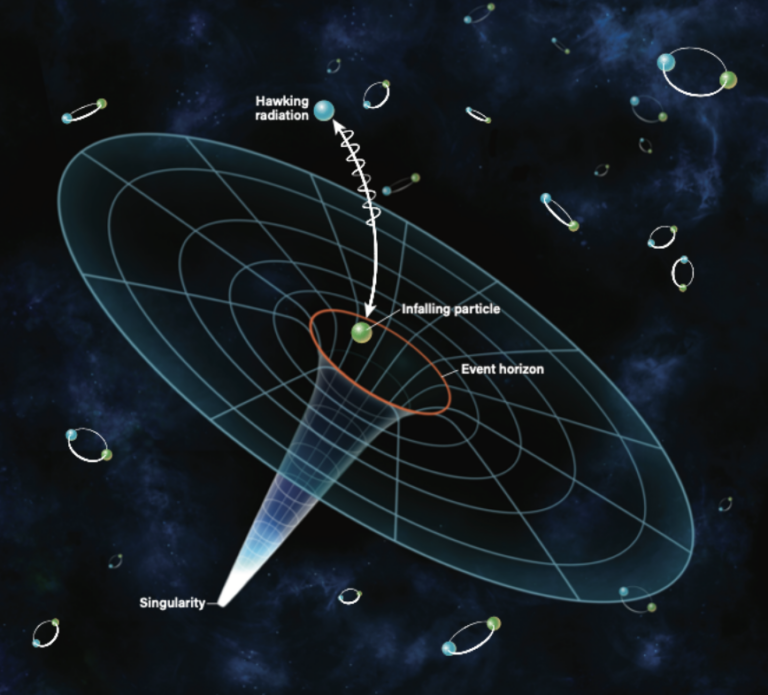

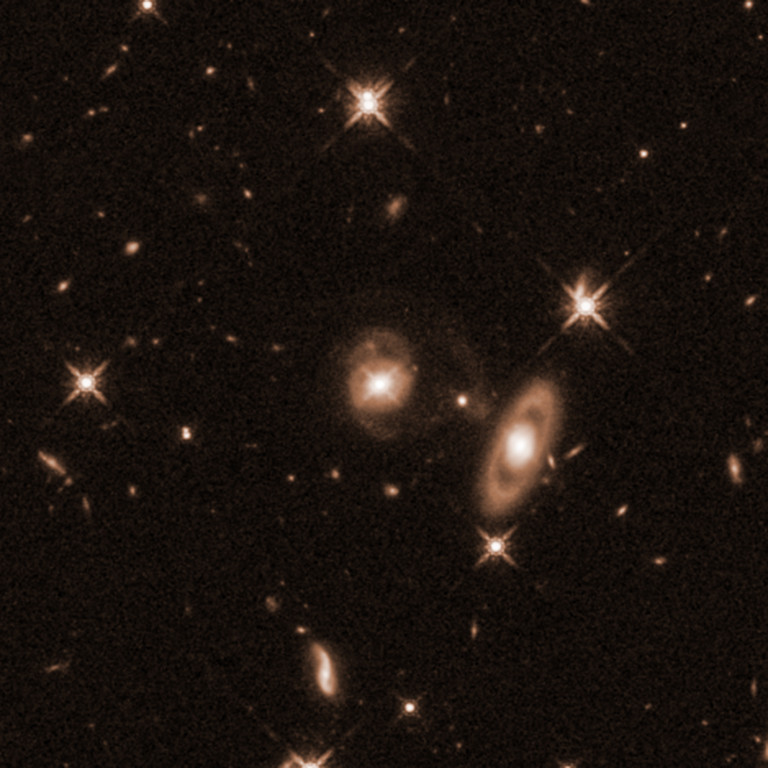

It turns out a funny thing happens when black holes collide. They spiral toward each other and merge into a single entity. In some cases, a gravitational “slingshot” effect then violently whips them outside their host galaxies into intergalactic space. The ejection mechanism results from a byproduct of the merger: gravitational waves. The gravitational waves can actually kick the merged black hole far away from the site of its merger. In 2017, astronomers found compelling evidence of such a mechanism when they used Hubble to image quasar 3C 186. Observations of the offset quasar suggested that it was jettisoned from the core of its galaxy by gravitational waves produced by the merger of two supermassive black holes.

But what role does this process play in building black holes? Could large numbers of black holes exist outside galaxies, where their presence would be extremely difficult to detect? These questions and others are still on the table. Although scientists have already detected gravitational waves from five merging pairs of stellar-mass black holes, researchers are tuning up their detectors for another observing run in early 2019, hoping more data will further illuminate the subject.

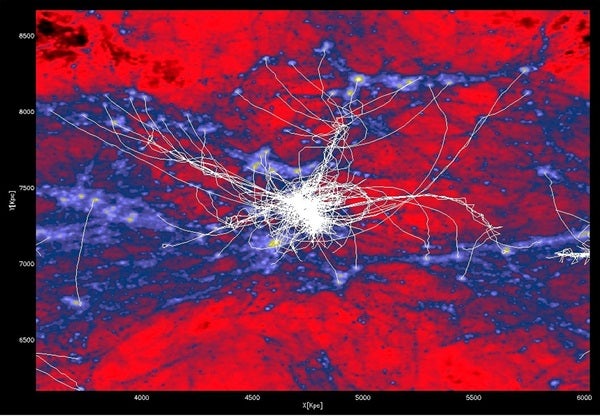

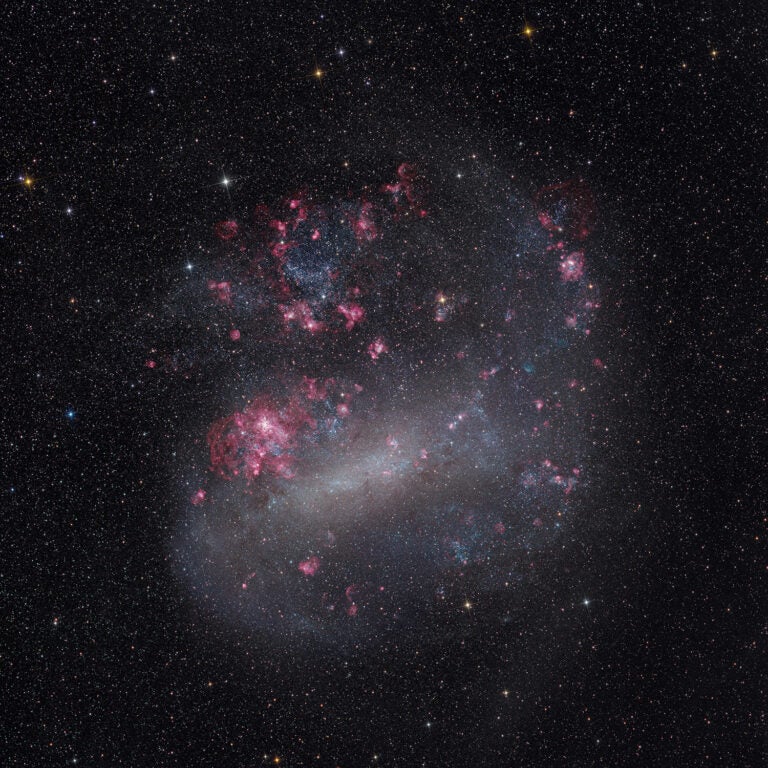

“Almost all large galaxies contain black holes,” says Hughes, “and galaxies merge like mad — especially a couple billion years ago.” Hughes believes binary black holes could have formed and be forming yet today, but detecting them observationally will be difficult. “We’re talking about two incredibly small bodies separated by a parsec,” he says, merely 3.26 light-years in galaxies that span hundreds of thousands of light-years across.

“Almost all large galaxies contain black holes,” says Hughes, “and galaxies merge like mad — especially a couple billion years ago.” However, detecting them is still difficult.

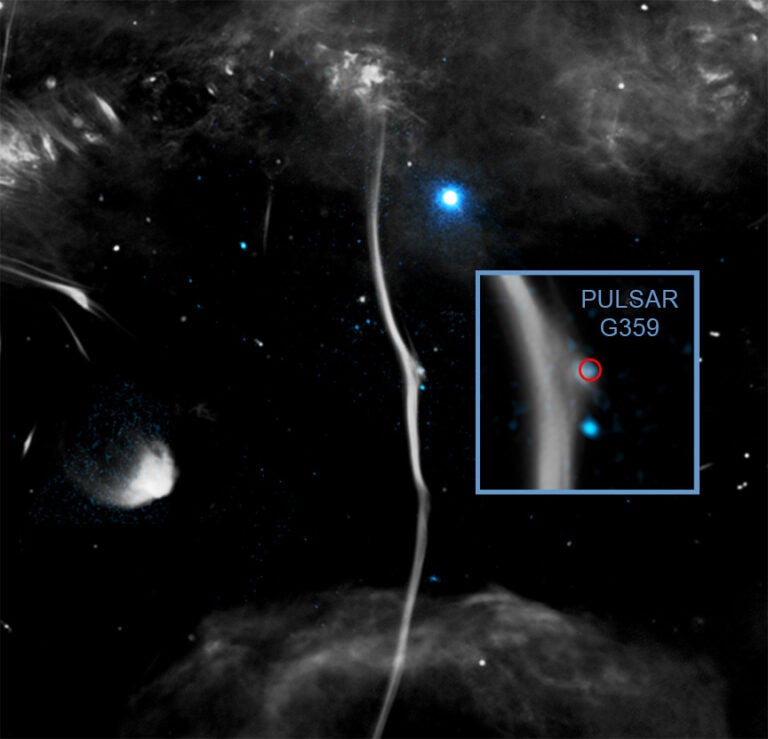

Black holes escaping their parent galaxies would be shot out at high velocities, probably 685,000 mph (1.1 million km/h). Such high-speed objects eventually might join other nomadic black holes in deep space. These freeform black holes would prove elusive. “If they’re not shining [from radiation produced by swallowing nearby bright material], it’s hard to know where to look,” according to Piero Madau of the University of California, Santa Cruz. One way to detect intergalactic black holes would be from gravitational-lensing effects. Another method, first outlined by University of Cambridge researchers in 2016, would be to measure Doppler shifts in gravitational-wave signals, which would reveal how hard a black hole is kicked.

Intergalactic black holes could absorb material without radiating and so continue along below the radar. “For that reason,” says Mitch Begelman of the University of Colorado, “we can’t rule out the possibility that black holes outside galaxies contain more mass than black holes inside galaxies.”

The evidence for small black holes gone missing from normal galaxies does hold some potential. According to David Merritt of the Rochester Institute of Technology, “As we look at ever smaller galaxies, there’s a point where you stop seeing black holes.” Merritt and other astronomers wonder if smaller galaxies may have had their small stellar black holes shot out into intergalactic space.

Further study of black-hole mergers could pay off big dividends when it comes to understanding large black holes in the early universe. Do they form by the process of mergers or by gradual accretion? Observational tests for determining how big black holes formed in the early cosmos are lacking; perhaps further study of how smaller black holes behave in more recent times will continue to shed light on this question.