Key Takeaways:

Years ago, planetary scientists thought of Venus as Earth’s sister planet. Similar in size, both close to the Sun, both rocky bodies, Earth and Venus were practically considered two of a kind. That abruptly changed, however, when astronomers got their first close-up look at Venus. The moment arrived in 1962, when Mariner 2 flew by the planet, and far more forcefully in 1970, when Venera 7 touched down on the hellishly hot surface. Not only do surface temperatures on our sister planet exceed 750° F (400° C), but Venus’ thick carbon-dioxide atmosphere produces a greenhouse effect that hosts sulfur-dioxide and sulfuric-acid clouds. It’s not a friendly environment for living things of any sort.

Scientists’ understanding of Venus and its geology catapulted forward with the most significant mission thus far, the Magellan spacecraft. It arrived in venusian orbit in 1990 and continued to collect data through 1994.

Bringing the universe to your door. We’re excited to announce Astronomy magazine’s new Space and Beyond subscription box – a quarterly adventure, curated with an astronomy-themed collection in every box. Learn More >>.

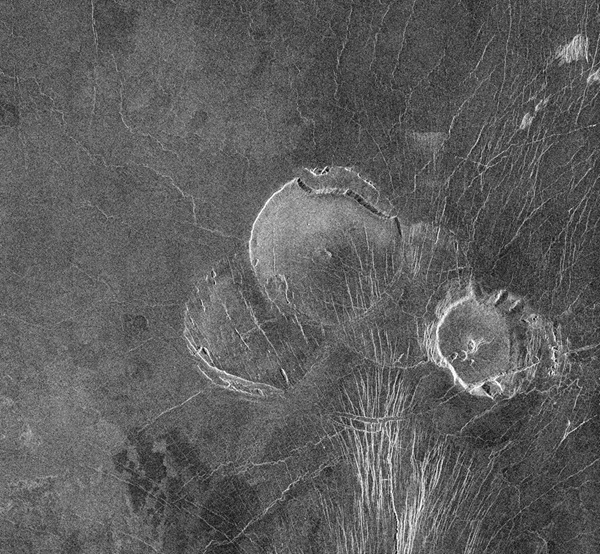

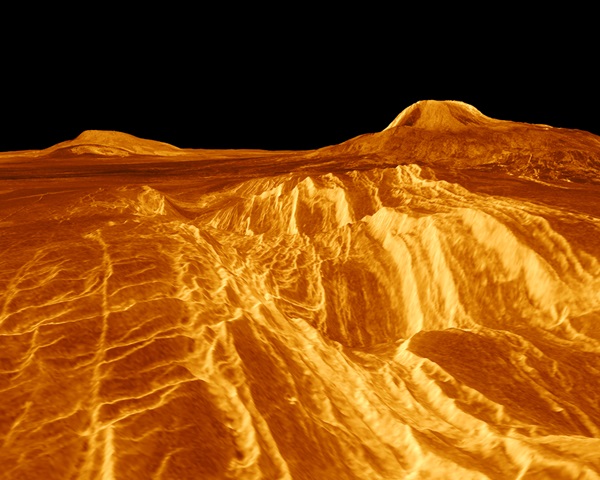

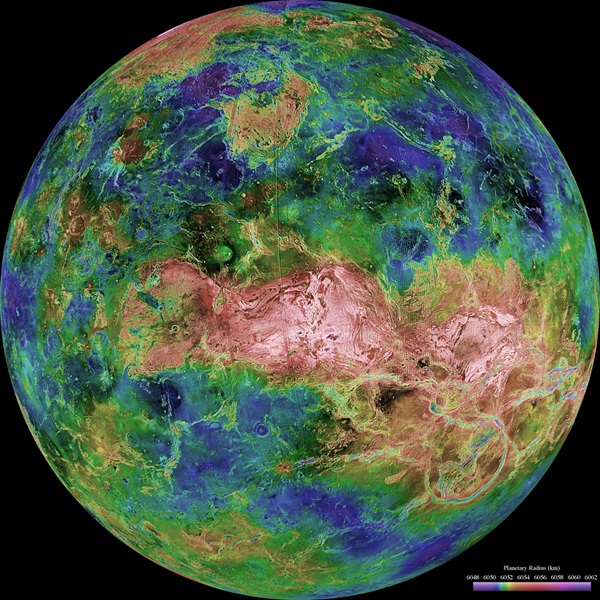

Magellan mapped 98 percent of the planet’s surface and returned thousands of spectacular views of Venus’ geological features. Almost one-quarter of the images returned by Magellan became computerized, 3-D images of regions with altitude effects exaggerated by the image processors. For the first time, humans had a good look at what Venus is really like.

There were surprises. The most amazing was the relative lack of craters compared with other inner solar system bodies like the Moon, Mars, and Mercury. Water, wind, volcanoes, and tectonic shifts constantly resurface our planet. Venus must be hiding many old craters, too. Astronomers wondered what resurfacing forces could keep Venus’ surface looking so young.

Astronomers observed other weird artifacts on the planet’s surface, in addition to many substantial volcanoes that suggest an active geology in the recent past. These include coronae (crown-shaped surface features), tesserae (crunched features where the planet’s crust is pushed together and buckles), and arachnoids (circular or oval features filled with concentric rings) — so named because they are spider-like in appearance. Moreover, scientists found trace signs of erosion and tectonic shifts on our sister planet.

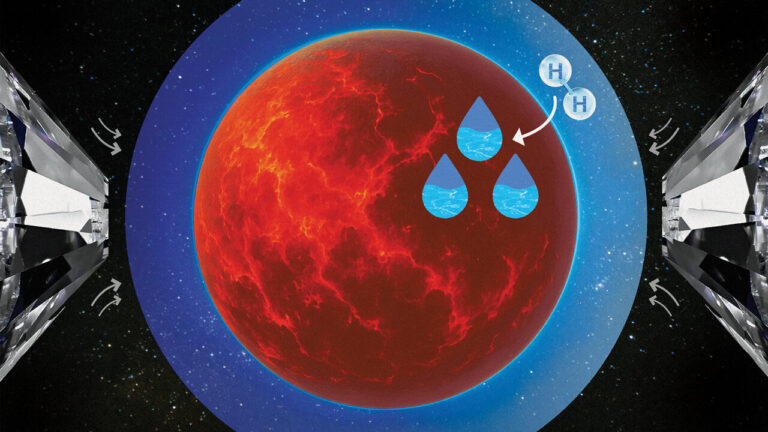

As scientists looked more carefully at the body of data returned from Magellan, it became clearer that this was a planet that had, somehow, turned itself inside out. Dating various features on the planet’s surface subsequently revealed Venus must have undergone a cataclysmic upheaval about 750 million years ago, very recently in geologic terms. At about that time, Venus’ surface seems to have been completely wiped clean.

Planetary scientists believe strongly in the gradual, slow, methodical workings of nature. Venus’ geology placed them in an awkward position because a huge catastrophic event apparently attacked the planet suddenly.

Nonetheless, in 1992, Gerald Schaber of the U.S. Geological Survey wrote that what was observed on the planet may have resulted from a “global resurfacing event or events.” Don Turcotte of Cornell University followed a year later, proposing the venusian crust may have grown so thick over time that it trapped the planet’s heat inside, which eventually flooded the planet with molten lava. Turcotte described the process as cyclical, suggesting that the event of several hundred million years ago may have been just one in a series.

Others have suggested that low-level volcanism may be responsible for coating the planet’s surface over time without a need for any global catastrophes. The European Venus Express spacecraft, which orbited the planet between 2006 and 2014, found the best evidence to date that Venus has been volcanically active in the recent geological past. “All the geologists agree,” says Schaber, “something very strange happened.” However scientists still have work to do before they can pinpoint the exact mechanisms that caused Venus to undergo a makeover.