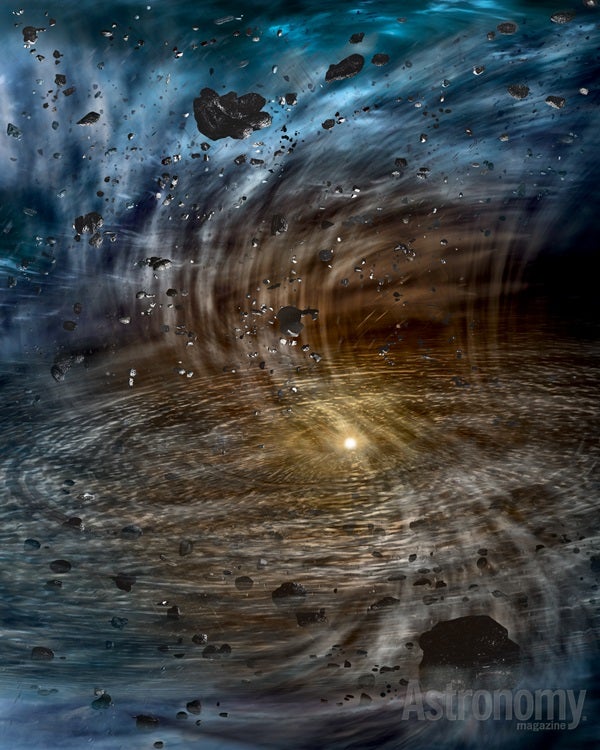

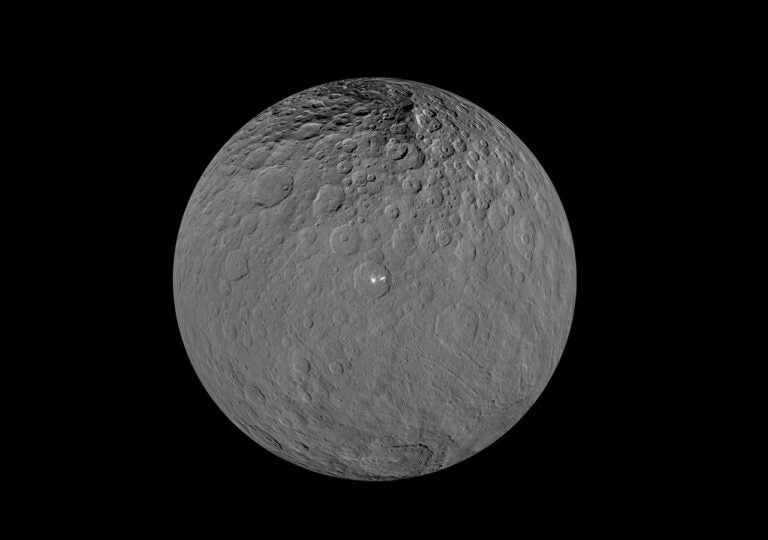

Although we live in relative quiet within the cosmos, going about our lives and seeing the stars as a distant backdrop, we are very much part of the universe that surrounds us. Dangers lurk in space, as any glance at the Moon’s cratered surface confirms.

Not only must our planet avoid collisions with Earth-crossing asteroids, but more remote threats exist. If a nearby star went supernova, a gamma-ray burst erupted nearby, or a black hole or stream of antimatter somehow wandered into our neighborhood, it could spell disaster. While astronomers say those events are unlikely, another dark, distant interloper could create havoc on Earth by its mere presence.

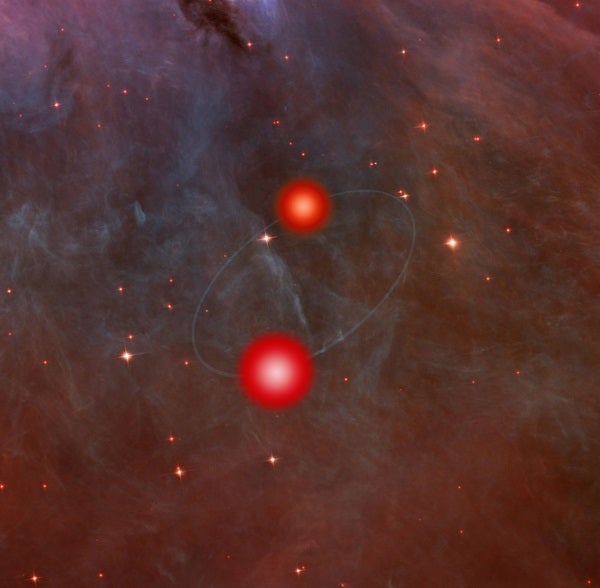

Where could such trouble come from? The Sun hasn’t always been a solitary star. It was born in a group of suns, as all stars are, and its native companions have been scattered by the gravitational tug created by orbiting the galaxy’s center.

Yet some 5 billion years after the Sun’s birth, a few of its associates still linger near the old neighborhood. Among them are the Sun-like star Alpha (α) Centauri, the yellowish dwarf Tau (τ) Ceti, and the cool red dwarf Wolf 359. Is the Sun truly single, or could a cool, dark companion loom in the background, periodically nudging comets toward Earth?

The discovery of Sedna, a trans-Neptunian object found in 2003, and the subsequent discovery of Eris, fueled the idea that large, dark bodies float in the solar system’s distant reaches. Those bodies exist apart from the numerous comets that populate the Oort Cloud. Close passages of well-known stars will occur far on down the line: For example, in less than a million and a half years, Gliese 710, a red dwarf now 60 light-years away, will slide within a light-year of the Sun. This will unleash a torrent of comets from the Oort Cloud into orbits that could intersect Earth’s, and they will arrive near our planet within a liberal span of about 2 million years.

But bombings from comet nuclei could result from other sources, too. A number of astronomers suggest the Sun may have a hidden, dark companion that periodically sends comets sunward, raining them down on the inner solar system.

In 1984, University of Chicago paleontologists David Raup and J. John Sepkoski revealed their finding that Earth’s extinction events were periodic. At the time, they suggested the Sun’s orbit about the Milky Way’s center was responsible, unleashing comets at regular intervals of about 26 million years.

In the same year, University of California, Berkeley, physicist Richard Muller proposed the responsible mechanism was “Nemesis,” an unseen, distant stellar companion to the Sun. Muller thought an M dwarf — a small, cool star — could lurk unnoticed in the distance yet have a huge effect on the Oort Cloud.

With the advent of the Two Micron All-Sky Survey (2MASS), however, astronomers scoured the whole sky at near-infrared wavelengths, producing 2 million images that would have uncovered Nemesis, had it existed. So the mystery of what lurks out in the darkness beyond the Oort Cloud, if anything, continues.

Not all scientists are unconcerned about the idea of a dark threat. Michael Rampino, a geologist at New York University, searches for an astronomical object he believes may be responsible for recurring extinction events every 25 to 35 million years.

As suggestive evidence, Rampino employs the large-impact events that produced craters under the Chesapeake Bay between Virginia and Maryland and in Popigai, Siberia, about 35 million years ago and the K-T impact in the Yucatán Peninsula, the “dinosaur-killer” that occurred 65 million years ago. Rampino believes several smaller lines of evidence suggest another catastrophic impact 95 million years ago.

If a dark monster is out there, it could be a small brown dwarf. If such a starlet exists, it might weigh less than 40 Jupiter masses, making it slip under the radar of the 2MASS survey. It would have a highly elliptical orbit that would make it hard to spot because most of its time would be spent far from us. Still, most astronomers remain skeptical. Only time will tell.