Galaxies in groups and clusters frequently pass close to one another. They sometimes collide and merge in spectacular fashion.

The Milky Way is a dominant member of a tribe of galaxies called the Local Group. Astronomers currently recognize about 50 members, most of which are quite small. Although there’s a great deal of space between the galaxies in the Local Group, the question arises: Will the Milky Way merge with one of its neighbors?

In fact, our galaxy formed from past mergers, and it will be the scene of many to come. The likeliest scenario of galaxy formation and evolution suggests that galaxies grew in the early universe by merging with many small protogalaxies. Scientists think that during its first few billion years, our galaxy shredded and cannibalized as many as 100 protogalaxies.

Bringing the universe to your door. We’re excited to announce Astronomy magazine’s new Space and Beyond subscription box – a quarterly adventure, curated with an astronomy-themed collection in every box. Learn More >>.

But the galaxy’s merger-mania continues. Astronomers see evidence that the Milky Way has gobbled up as few as five and perhaps as many as 11 small galaxies in the past few hundred million years. These mergers don’t result in the massive bursts of star formation astronomers observe when two large galaxies come together. Instead, these mergers occur as the Milky Way rips apart and slowly absorbs small dwarf galaxies that have strayed too close.

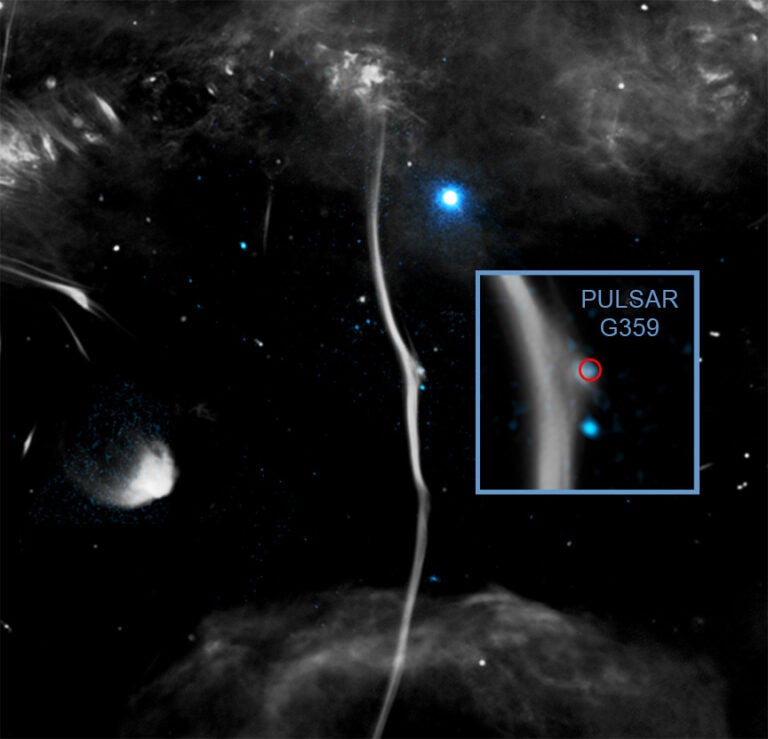

How do astronomers know about the Milky Way’s ancient galaxy mergers? The evidence lies scattered in the record of globular star clusters and old stars orbiting in the galaxy’s halo, which extends far above and below its disk.

Astronomer Dougal Mackey, now at the Australian National Observatory, has studied these objects extensively. He finds that older clusters are remnants from the Milky Way’s formation. Younger ones, however, may be imports carried into the Milky Way from dwarf galaxies it has absorbed. Cataloging these objects, their positions, velocities, and nature can help astronomers reconstruct our galaxy’s merger history.

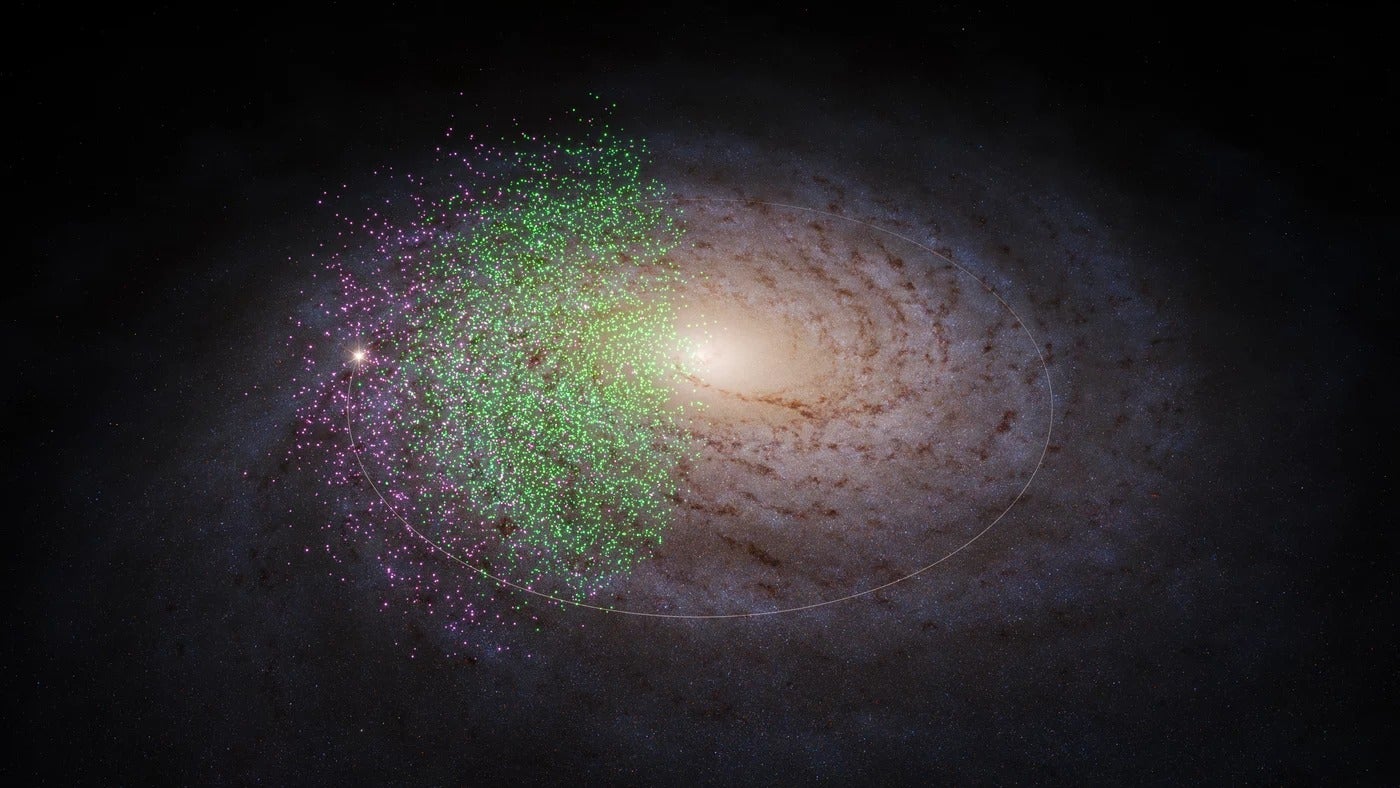

At least one merger is under way now. A small dwarf galaxy called the Sagittarius Dwarf Spheroidal is being torn apart and absorbed by the Milky Way. The galaxy lies in Sagittarius, and a stream of stars, gas, and debris over other parts of the sky show it is being shredded. Along with astronomer Gerry Gilmore, Mackey suspects the Milky Way may have experienced seven recent mergers with dwarf galaxies like this one.

“A handful of mergers is not inconsistent with the remnants that we see,” Mackey says. “In my opinion, there’s no doubt more remnants are to be discovered yet, probably in the form of stellar streams like those observed from Sagittarius.” In fact, at the beginning of 2018, astronomers announced the discovery of 11 new stellar streams within the Milky Way, bringing the total number of streams up to about 35.

Eating dwarf spheroidal galaxies is one thing. Major mergers are far more explosive, far more traumatic. The Milky Way is due for one several billion years from now with none other than the most famous galaxy in the sky, the Andromeda Galaxy (M31). This largest member of the Local Group, a favorite of backyard observers, is moving toward the Milky Way at about 250,000 mph (400,000 km/h). At this speed, 3 to 4 billion years from now, the two giant spirals will begin to merge. The result may resemble the Antennae or Mice galaxies we now see locked in embrace.

t’s quite likely to be a rather messy affair,” says Mackey of the future Andromeda encounter. “The gravitational forces between the two galaxies will distort and disrupt them both, sending vast plumes of stars out into intergalactic space, never to return. The first close pass will excite tidal tails and will also probably result in a ‘bridge’ of stars between the Milky Way and Andromeda.”

Mackey further explains: “After the first close pass, the galaxies will move apart and then fall back together a second time, sending out more stellar streams and further disrupting each galaxy. This cycle will occur several additional times, producing ever more complex patterns of ejected stars.”

The interaction will hurl stars, dust clouds, gas, and planets into space, but each pass will bring the two distorted galaxies closer. “Eventually, the densest regions of the two galaxies will merge, surrounded by a complicated mixed halo of stars,” Mackey says.

Those will be exciting times for inhabitants of the Milky Way.