Even though Mercury lies tantalizingly close to Earth, it is frustratingly hard to get to. Only two spacecraft have ever visited this barren world. But that is set to change October 19, when the international BepiColombo spacecraft begins a decade-long odyssey to unlock the secrets of a planet that seems to defy common sense.

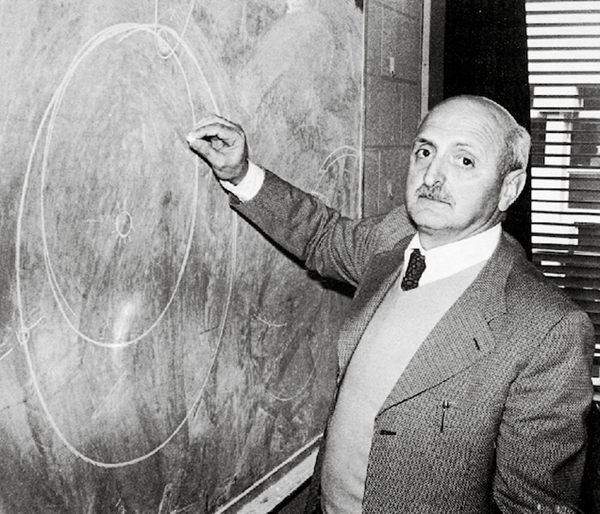

The mission’s namesake — Italian scientist, mathematician, and engineer Giuseppe “Bepi” Colombo (1920–1984) — was instrumental in devising a means to deliver a spacecraft from Earth, via Venus, to Mercury. Scientists already knew that a planet’s gravitational field could bend the trajectory of a passing spacecraft and enable it to rendezvous with another celestial body. In the early 1970s, Colombo showed that if a spacecraft encountered Mercury, it would end up with a period almost twice that of the planet’s orbital period. He suggested that a precisely targeted flyby would present a possibility for an economical second encounter.

NASA confirmed the idea and used it to send the Mariner 10 spacecraft past the innermost planet three times. The probe encountered Mercury in March 1974, September 1974, and March 1975. Its photographs gave humanity its first close-up views of the world, and the last ones we would see for a generation.

As Colombo first described, this means a day on Mercury lasts twice as long as its year. Day and night each last a mercurian year apiece, with new sunrises arriving every 176 days — the same as the six-month interval between Mariner 10 flybys. So, the Sun illuminated the same hemisphere of Mercury during all three encounters, and the spacecraft was able to map only about 45 percent of the planet’s surface.

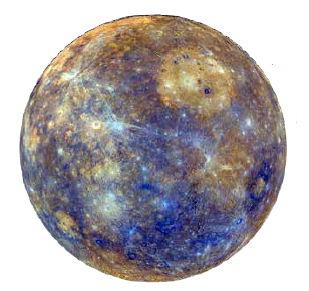

A strange, old world

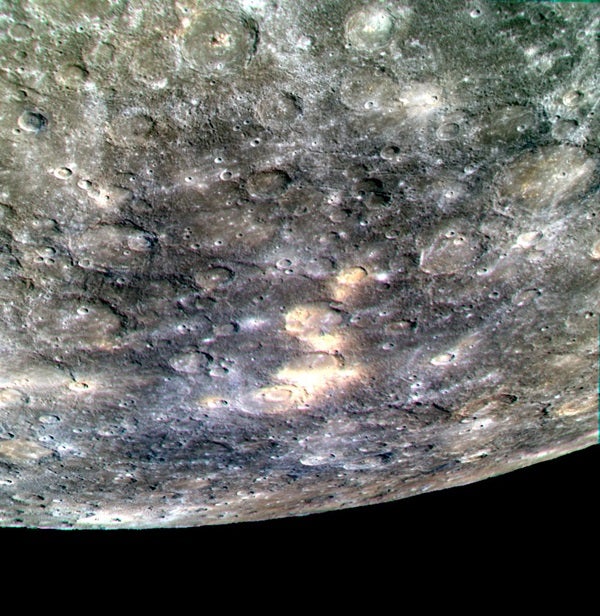

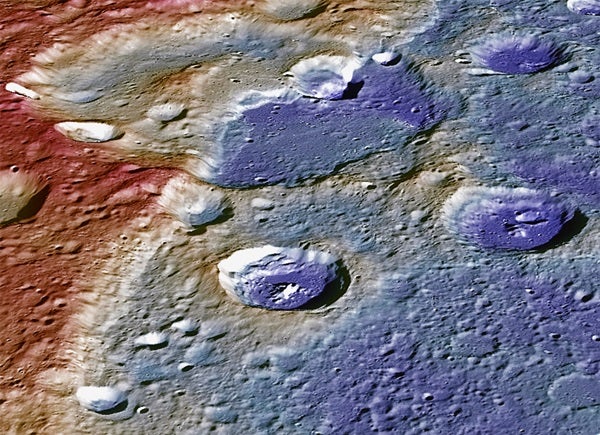

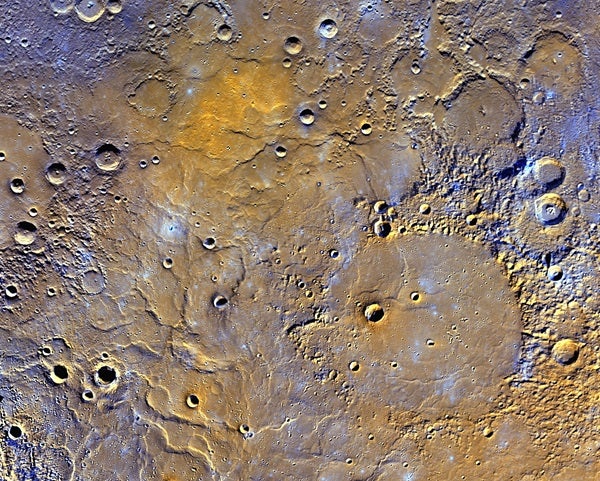

Mariner 10 revealed an ancient terrain of rugged highlands and smooth lowlands, strikingly reminiscent of our Moon. Yet the similarities aren’t even skin deep. Mercury’s craters differ markedly from lunar ones, because their impact ejecta blankets a smaller area, partly due to the planet’s much stronger gravity. The highland regions are less saturated with craters; instead they are mixed with rolling “intercrater plains” that constitute one of the oldest-known surfaces on the terrestrial planets.

The plains were laid down some 4.2 billion years ago during the Late Heavy Bombardment, when remnants from the solar system’s birth rained down on the infant planets. Mercury was only a few hundred million years old, and the plains obliterated older craters, buried several large basins, and carved many of the pits and bowls seen today. The plains boast groups of secondary craters that occur in chains and clusters, covering the highlands.

Mariner 10’s successor, NASA’s MESSENGER spacecraft, provided the proof. During its initial flyby in January 2008, the probe revealed a fractured region of ridges and furrows within the huge Caloris Basin. MESSENGER would go on to fly past Mercury twice more, in October 2008 and September 2009, and then orbit the inner world for four years starting in March 2011. While in orbit, the spacecraft discovered at least nine overlapping volcanic vents, each up to 5 miles (8 km) across and a billion years old, near Caloris’ southwestern rim. Elsewhere on Mercury, MESSENGER uncovered residue from more than 50 ancient pyroclastic flows — violent outbursts of hot rock and gas — tracing back to low-profile shield volcanoes, mainly within impact craters.

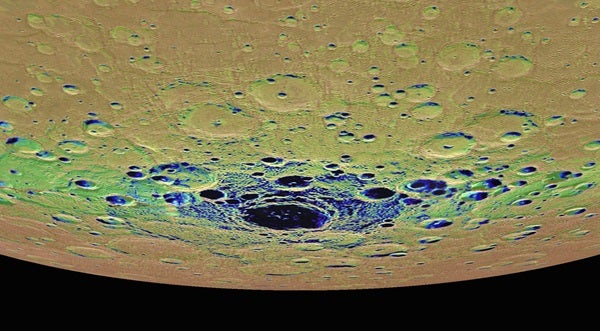

Caloris itself is an impressive relic from Mercury’s tumultuous early days. The Sun illuminated only half the basin during Mariner 10’s visits, so it was left to MESSENGER to fully reveal its structure. Caloris spans 960 miles (1,550 km), placing it among the largest impact features in the solar system, and it is ringed by a forbidding chain of mountains that rises 1.2 miles (2 km) above the surroundings. Beyond its walls, ejecta radiate in meandering ridges and grooves for more than 600 miles (1,000 km). The impact that created Caloris was so globally cataclysmic that strong seismic waves pulsed through Mercury’s interior and fragmented the landscape on the planet’s opposite side, leaving a region of jumbled rocks, hills, and furrows that some scientists have dubbed “weird terrain.”

Despite Caloris’ huge dimensions, Mercury itself is quite small — just 3,032 miles (4,879 km) in diameter. The planet’s small size and high temperature led mid-20th-century astronomers to suspect it could not retain an atmosphere. But Mercury is full of surprises. Mariner 10 discovered a thin layer of loosely bound atoms, known as an exosphere, albeit with a surface pressure trillions of times less than that at sea level on Earth. It contains hydrogen and helium atoms captured from the solar wind — the stream of charged particles emanating from the Sun — together with oxygen atoms liberated from the surface by micrometeoroid impacts. Spectroscopic observations also revealed sodium, potassium, calcium, magnesium, and silicon. Caloris and the weird terrain appear to be key sources of sodium and potassium, indicating that impacts can release gases from below the surface.

Digging deeper

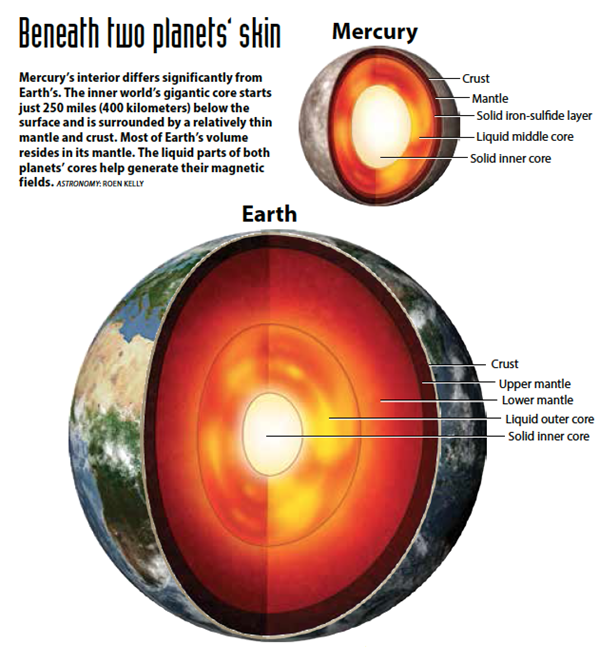

Farther down, the planet’s interior remains a puzzle. Before Mariner 10, scientists assumed Mercury had a solid interior that produced no intrinsic magnetic field. They did realize, however, that the planet has an inordinately high density. Overall, Mercury’s density averages 5.4 times that of water, close to those of the much larger Earth (5.5 times water) and Venus (5.2 times water). But the gravity of these bigger worlds crushes their interiors to far higher densities than they would have otherwise.

The only reasonable way to explain Mercury’s high density is with the presence of heavy elements — some 70 percent iron and nickel overall — with most of them concentrated in the planet’s giant core. This makes Mercury by far the most iron-rich planet in the solar system. Scientists think the winding cliffs that reach up to a mile high and run for hundreds of miles formed when the surface buckled as the interior cooled and contracted. Despite this shrinkage, MESSENGER revealed that Mercury’s core stretches to within 250 miles (400 km) of its surface.

Scientists also were surprised when Mariner 10 discovered a magnetic field together with a small magnetosphere that weakly deflects the solar wind around the planet. A solid, slowly rotating planet shouldn’t be able to generate the strong internal dynamo needed to create an intrinsic field, even one that’s just 1 percent as strong as Earth’s. MESSENGER showed the field is offset along the rotational axis by 20 percent of Mercury’s radius and suggested that the planet possesses a partially molten outer core that surrounds a solid inner core.

Astronomers still aren’t sure what keeps the core in an electrically conductive, semi-liquid state. Perhaps it is the slow decay of the radioactive elements Mercury was born with. The Sun’s gravity, which raises tides as the planet follows its eccentric orbit, could flex the interior and play a contributing role.

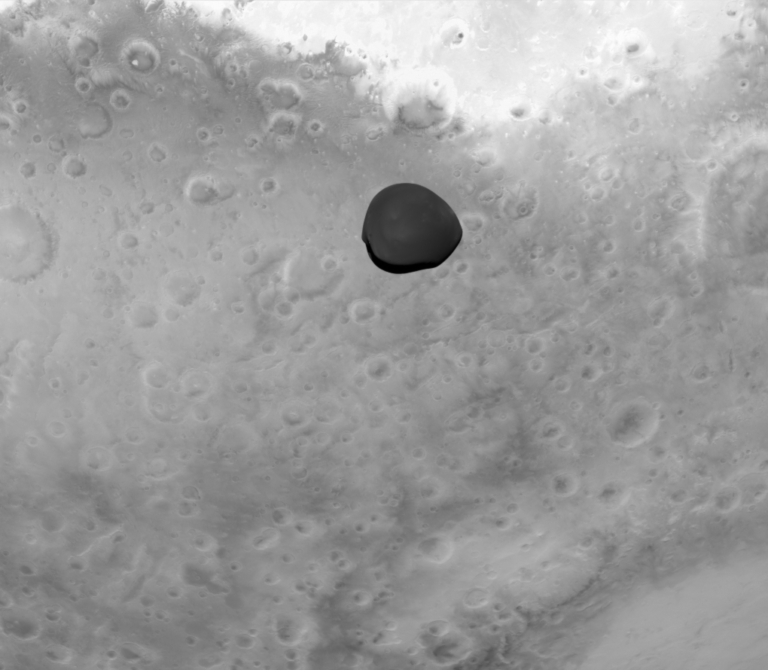

Despite this internal heat and the blazing Sun above, Mercury also appears to be a land of ice. In the 1990s, ground-based radar observations revealed a number of bright spots within 6.5° of the planet’s north and south poles. Many scientists interpreted these findings as evidence for ice deposits on the floors of permanently shadowed craters, where temperatures can drop as low as –370 F (–225 C). In November 2012, MESSENGER identified up to 1 trillion tons of water ice near the poles — enough to encase Washington, D.C., in a frozen block 2.5 miles (4 km) deep.

BepiColombo comes on the scene

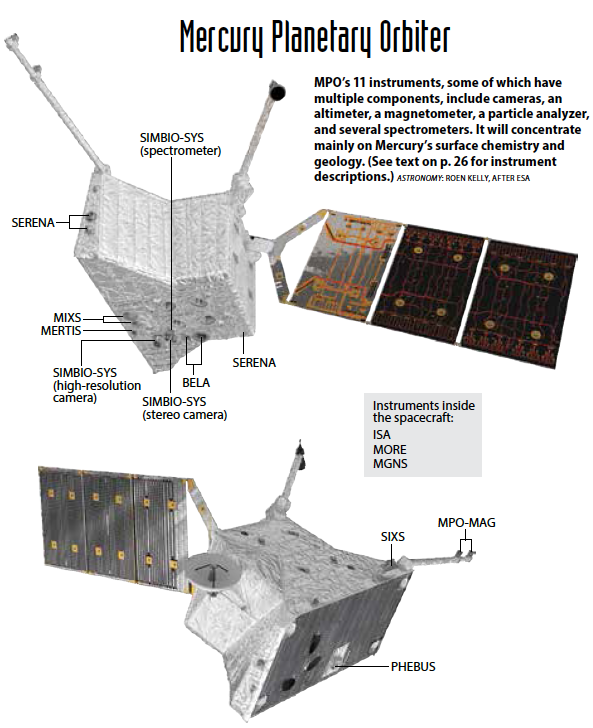

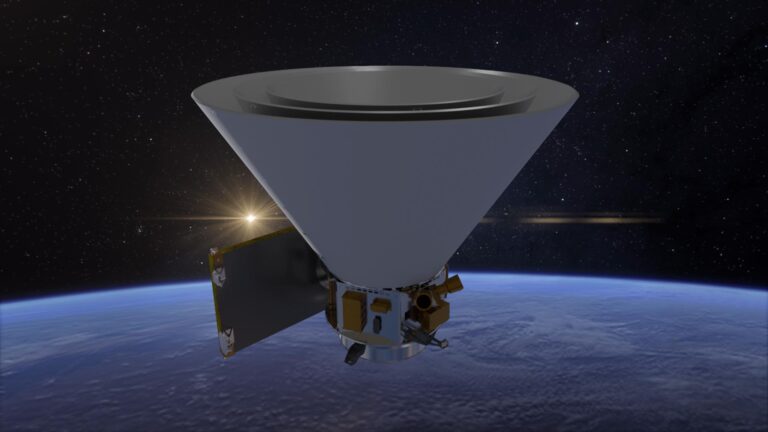

Despite Mariner 10’s and MESSENGER’s incredible discoveries, scientists still have many questions about this enigmatic world. That’s where BepiColombo comes in. The European Space Agency (ESA) initially envisioned three spacecraft for this ambitious venture: The Mercury Planetary Orbiter (MPO) and Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter (MMO) would work in tandem to unlock Mercury’s mysteries from above, and the Mercury Surface Element (MSE) would explore the surface. ESA planned to land the MSE near the day-night terminator and have it survive for about a week in the harsh environment. The lander would carry heat-flow sensors, a spectrometer, a magnetometer, a seismometer, a soil-penetrating device, and a tiny rover.

Unfortunately, budget considerations forced ESA to abandon the lander in November 2003. “The decision to cancel the lander was a loss for the mission,” says BepiColombo project scientist Johannes Benkhoff. “What we miss is a so-called ‘ground truth.’ We can do many things remotely with our instruments, which are already on the other spacecraft, but the measurements of a lander would have been used to calibrate them, and that can unfortunately not be recovered.”

The rest of the mission continued, however. ESA led the development of the 2,535-pound (1,150 kilograms) MPO spacecraft. The probe’s 11 instruments were fabricated by 35 scientific and industrial teams in Switzerland, Germany, Italy, the United Kingdom, Russia, Finland, Sweden, Austria, France, and the United States.

The BepiColombo Laser Altimeter (BELA) and the Spectrometers and Imagers for MPO BepiColombo Integrated Observatory System (SIMBIO-SYS) will create digital terrain models to quantitatively map Mercury’s geology, elemental composition, and surface age. Together with the Mercury Radiometer and Thermal Infrared Spectrometer (MERTIS), Mercury Gamma-Ray and Neutron Spectrometer (MGNS), and Mercury Imaging X-Ray Spectrometer (MIXS), they will identify key rock-forming minerals, measure global surface temperatures, and address competing theories of the planet’s origin and evolution. These tools also will search for additional ice deposits and other volatile substances at high latitudes as well as provide insights into the role of volcanism.

MPO carries two instruments to help understand why Mercury has so much iron and what this reveals about its evolutionary history. The Italian Spring Accelerometer (ISA) and Mercury Orbiter Radioscience Experiment (MORE) will investigate the planet’s global gravitational field to understand the size and nature of the core as well as the structure of the mantle and crust. MPO also houses one-half of the Mercury Magnetometer (MERMAG) that will study the magnetic field for clues to the dynamo lurking inside.

MPO carries a 24.6-foot-long (7.5 meters) solar array with integrated optical reflectors designed to keep the spacecraft at a temperature below 390 F (200 C). When in orbit around Mercury, the array must continuously rotate to balance MPO’s power requirements with the need to keep the probe under its redline temperature. Meanwhile, a radiator angled toward the planet will reflect the intense infrared radiation coming from Mercury’s searing surface.

“The solar arrays will be exposed to high-frequency, high-intensity ultraviolet radiation, combined with high temperatures, which was discovered to induce an unexpectedly fast degradation in solar-cell performance,” explains BepiColombo project manager Ulrich Reininghaus. “This was resolved by a complex method of continuous solar array steering control, in order to maintain the temperature always below an allowed maximum, and by a specific redesign of the solar cells.”

Japan lends a hand

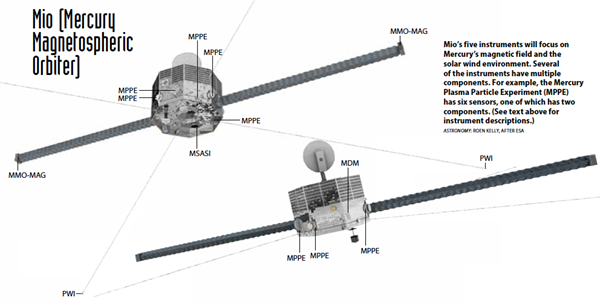

The mission drew more international collaboration when the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) joined the project. JAXA developed the 630-pound (285 kg) MMO spacecraft. Earlier this year, the space agency renamed the craft Mio, which comes from a Japanese word meaning “waterway” or “fairway.”

Mio carries five science instruments, including the second half of MERMAG. Its other tools are the Mercury Sodium Atmosphere Spectral Imager (MSASI), to study the origin and extent of sodium in the exosphere; the Mercury Dust Monitor (MDM), to explore space dust in the planet’s vicinity and how it weathers the mercurian surface; the Mercury Plasma Particle Experiment (MPPE), to scrutinize the planet’s magnetic field and its interaction with particles in the solar wind and particles coming from Mercury; and the Plasma Wave Investigation (PWI), to study the planet’s electric and magnetic fields as well as look for evidence of aurorae and radiation belts.

“The collaboration with our Japanese colleagues goes very well; we almost feel as one team,” says Reininghaus. “However, the two spacecraft were designed and built totally independently, although we had to agree on interfaces. In the science area, we hold regular joint meetings. Some of our science goals can only be reached if we work closely together.”

The final element of the spacecraft is the Mercury Transport Module (MTM). It holds four British-built xenon-ion engines, 24 chemical thrusters, and two large solar arrays that will provide electrical power to keep MPO and Mio alive during their seven-year journey to the Sun’s closest planet. “Solar electric propulsion [SEP] allows very significant autonomous capabilities for readjusting the interplanetary trajectory, avoiding altogether large midcourse maneuvers,” says Reininghaus.

Although the solar electric thrusters provide low thrust, they operate over a long time, delivering what rocket scientists call high impulse. In fact, the thrusters will accumulate the greatest total impulse ever achieved by a space mission. This posed considerable challenges during preflight testing. “[We resolved this through] multiple test campaigns in different chambers and with different test articles, combined with a sophisticated modeling approach that allowed us to accurately predict end-of-life performance of the thrusters,” explains Benkhoff.

Getting there

Like Mariner 10 and MESSENGER before it, BepiColombo will take a circuitous route to reach Mercury. The spacecraft will launch from Kourou, French Guiana, atop a giant Ariane 5 rocket, perhaps as early as October 19 (the first chance during a six-week launch window). It will depart Earth 7,770 mph (12,510 km/h) faster than the escape velocity from our planet. Although impressive by many standards, this speed is problematic for a spacecraft heading directly into the Sun’s powerful gravitational field. In fact, the energy needed to get to Mercury is larger than it would be to reach Pluto and leave the solar system. Moreover, Mercury’s orbital velocity of 105,900 mph (170,500 km/h) is 60 percent greater than Earth’s, demanding a substantial velocity change and correspondingly high fuel consumption.

To overcome these obstacles, BepiColombo initially will enter an orbit similar to Earth’s, using its high-impulse, low-thrust xenon-ion engines to slowly decelerate against solar gravity and adjust its orbital plane. “Solar electric propulsion was the only option to reach Mercury,” says Benkhoff. “In principle, one can fly a mission to Mercury with chemical propulsion, but it all depends on the thrust-to-mass ratio. SEP is about eight times more efficient than chemical fuel. Thus, for BepiColombo, we would have needed at least 2 tons more mass to accommodate this.”

The spacecraft will complete 1.5 circuits of the Sun, returning to Earth in April 2020 to pick up a gravitational boost. This will propel it to Venus for rendezvous in October 2020 and August 2021, which will reduce BepiColombo’s perihelion to about the same distance as Mercury. Critically, this ingenious use of gravitational fields requires little propulsive intervention from the spacecraft. “These flybys depend on the [arrangement] of the planets, and that is the reason for the long duration,” says Benkhoff. “The flybys provide almost half of the needed energy to go to Mercury. The SEP engine will be used for about 50 percent of the time.”

Six flybys of Mercury between October 2021 and January 2025 will slow BepiColombo’s inbound trajectory until its orbit nearly matches that of the planet. Finally, in December 2025, Mercury will weakly capture the spacecraft into a polar orbit that comes within 420 miles (675 km) of the planet’s surface and swings out to 110,600 miles (178,000 km). This so-called weak-stability-boundary technique adds flexibility compared with traditional approaches, where a single engine firing typically brings a spacecraft into orbit. BepiColombo’s chemical thrusters will stabilize the orbit gradually and, after traveling 5.5 billion miles (8.9 billion km), the mission will at last be underway.

All told, the two spacecraft will bring about 275 pounds (125 kg) of scientific instruments to bear upon one of the least-known worlds in the solar system. MPO will occupy a looping, 2.3-hour orbit at a distance that ranges from 300 miles (480 km) to 930 miles (1,500 km); Mio will follow a highly elliptical path that will carry it as close to Mercury’s surface as 365 miles (590 km) and as far away as 7,230 miles (11,640 km) during a 9.3-hour orbit.

Scientists expect the baseline mission to last until May 2027, but there’s a good chance ESA will grant a one-year extension. As a bonus, BepiColombo will make precise measurements of Mercury’s orbital parameters. Because the planet lies so close to the Sun, this should allow astronomers to chart our star’s gravitational field in detail and provide a rigorous test of Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity.

Although the spacecraft’s roundabout route to Mercury is hardly in keeping with the fleet-footed nature of the planet’s mythological namesake, the mission and the god do share some similarities. Both will deliver an abundance of learning, and both will accomplish their goals through ingenuity, an element of trickery, and a pinch or two of old-fashioned good fortune.